The European Commission is homing in on the word “green.” When its policymakers in the spring of 2022 laid out a plan to make textiles more durable and recyclable by 2030, they addressed not only waste reduction and circularity, but also how the fashion industry communicates with its customers. The strategic roadmap aims to crack down on “greenwashing,” stating that terms like “eco-friendly” and “good for the environment” will be “allowed only if underpinned by recognised excellence in environmental performance.”

While the EU plan is not enforceable legislation, its policymakers — like those in other parts of the world — highlight thorny questions looming over the fashion industry in 2023: what is sustainable fashion and which brands — if any — can claim to sell it? While brands have grappled with their own answers for years, governments and regulatory bodies are signalling that existing definitions may be insufficient and, in many cases, misleading.

Consumer watchdogs in Norway and The Netherlands have ruled a number of high-profile marketing campaigns by big brands were misleading. In the UK, the Competition and Markets Authority launched a review of sustainability claims in the fashion retail sector in 2022, taking aim at fashion as one of the worst-offending industries when it comes to greenwashing. The review scrutinised fast-fashion brands that it believed may be using misleading language or cherry-picking information they share with consumers in a bid to appear more sustainable than they actually might be. As a result, some companies are overhauling how they present sustainability claims. Meanwhile in France, legislation expected in 2023 will require brands to add “carbon labels” to clothing and textiles, which will display an environmental “score” from A to E to help consumers make more informed purchase decisions.

This increased scrutiny and regulation come as a growing number of consumers place importance on the environmental or social impact of the fashion they buy. A quarter of respondents to a 2021 survey by McKinsey in the UK said their purchase decisions were driven by sustainability, while 80 percent of consumers in a US survey said sustainability was an important factor when selecting a fashion brand to shop from. In another 2021 survey in India, 94 percent of consumers said they were willing to pay high prices for “ethical” products. Younger consumers are especially motivated by sustainability concerns: half of Gen-Z shoppers in China said they aimed to buy less fast fashion in a recent survey about sustainable consumption.

Fashion companies have been responding to this growing interest in sustainability. Many have stepped up public disclosures of sustainability-focused initiatives in recent years, though evidence of progress from such initiatives is limited, the BoF Sustainability Index’s 2022 edition found.

In parallel, brands should be aware that even sustainability-focused consumers are struggling to make sense of the information they encounter while shopping. In a University of Melbourne survey of Australian consumers in 2019, most respondents were “overwhelmed” when trying to understand how garments are made and “deeply skeptical” of brands’ own claims. Similarly, American respondents in a 2021 survey conducted by biotech firm Genomatica echoed these views: 42 percent of the teenagers and adults polled said they were unsure what makes clothing sustainable, while 88 percent said they did not trust brands’ claims.

What’s In a Definition?

The complexity of sustainable business practices requires a holistic approach to tackle an array of environmental and social factors, from carbon emissions to garment workers’ rights. Within this, the industry does not always align on a shared vision for change, which can add to confusion among consumers. For example, while the leather supply chain is often associated with animal cruelty and “unsustainable” farming, many “sustainable” vegan alternatives are criticised for containing harmful amounts of plastic.

Any brand wanting to operate more responsibly faces tension when attempting to deliver on the promise of sustainability, leading some to even avoid using the term “sustainable” altogether. US outdoor clothing retailer Patagonia — despite its efforts to pioneer responsible business practices — does not refer to its business or products as “sustainable” as part of its company policy, explaining that “we recognise we are part of the problem.” Similarly, Ganni took to Instagram in 2021 to explain “why we’re not a sustainable brand,” instead highlighting its focus on being transparent and honest. The Danish fashion label, which worked with the United Nations Development Programme to create a zero-impact collection, clarified that criticisms about its progress “would most likely be justified.”

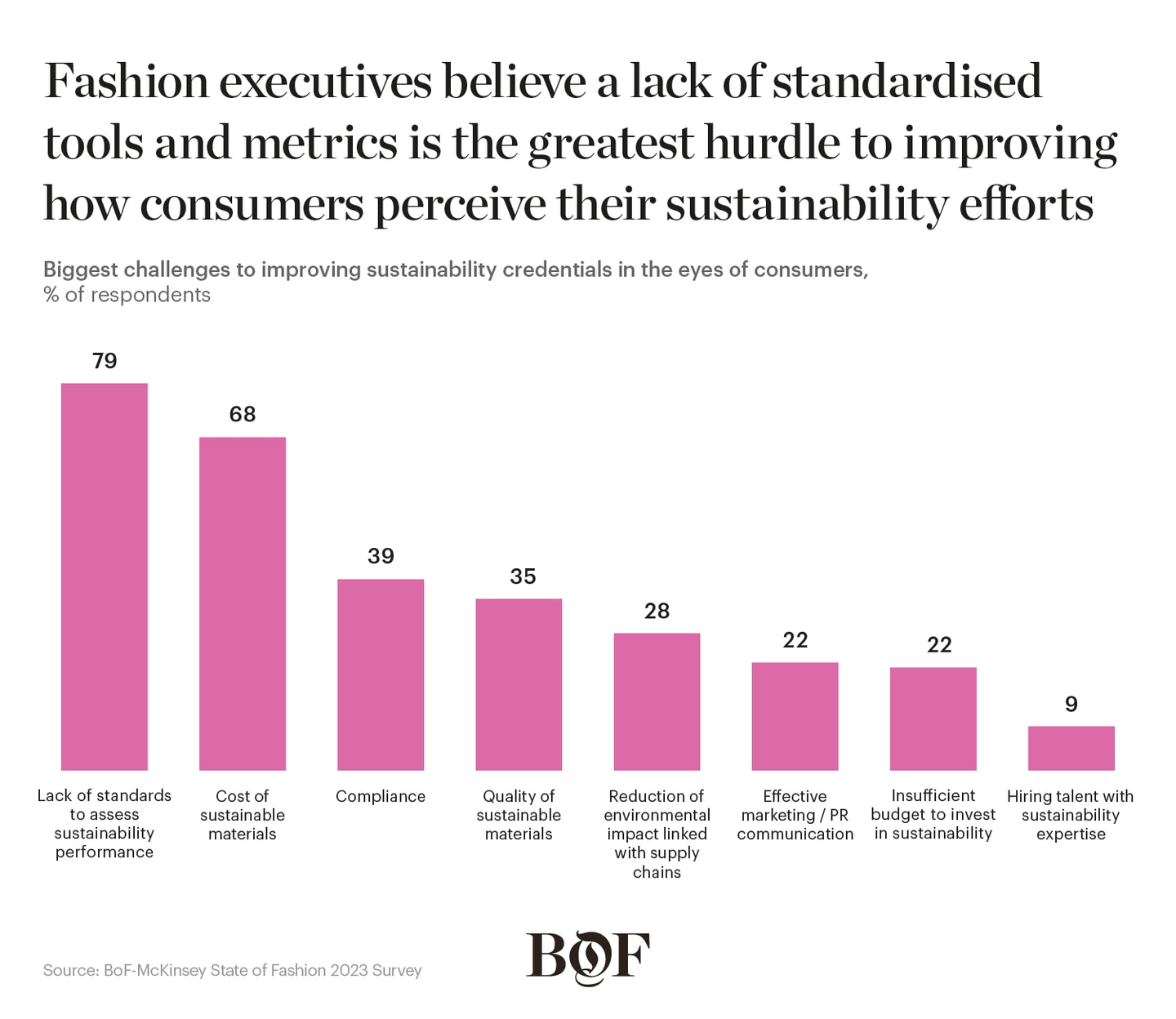

“With no standardised language or regulated frameworks, deciphering what companies are actually doing is extremely challenging,” said Kenneth P. Pucker, former chief operating officer of US outdoor footwear brand Timberland and now an advisory partner at Berkshire Partners, in 2022.

While third-party certification systems and impact assessment tools have emerged to guide brands and consumers, these have also stirred debate. In 2022, one of fashion’s most adopted rating systems, the Higg Index, faced a range of criticism, from the quality and accuracy of the data it provides to the potential for big brands to influence it. After ruling that the index’s consumer-facing effort can be misleading, Norway’s consumer authority banned reference to the Higg Index in marketing materials in June 2022. The Sustainable Apparel Coalition, the group behind the index, put the programme on pause and commissioned an independent review of its data and methodology.

Aligning Behind a Common Cause

The need for common frameworks is clear. In 2021 at the request of G20 leaders, the International Financial Reporting Standards body launched the International Financial Reporting Standards Board to provide a disclosure baseline to help capital markets participants track climate impact. “Rarely do governments, policymakers and the private sector align behind a common cause,” said Emmanuel Faber, chair of the ISSB. “However, all agree on the importance of high-quality, globally comparable sustainability information for the capital markets.”

The ISSB issued its first draft for the baseline in early 2022. The reporting system, if adopted widely, could allow investors as well as consumers to compare brands across industries. However, it might not be specific enough to highlight the fashion industry’s particular challenges.

At the same time, cross-player initiatives that seek to provide a framework for brands to assess and communicate their impact continue to emerge ahead of incoming regulation. In February 2022, 50 beauty companies, including The Estée Lauder Companies as well as professional associations, formed a consortium in partnership with independent bodies to develop an “eco beauty score” for cosmetics companies to assess their environmental impact. There is, however, a great deal of criticism facing industry-backed initiatives in general. As such, brands should ensure they work with independent third parties and conform to ongoing regulatory efforts to reduce concerns about their efficacy.

Before brands can accurately talk about their credentials, they should dig deep into their own operations and supply chains to gather data that they can benchmark effectively. For example, Swedish fashion brand Asket has invested in tracing its full supply chain and gathering data to communicate the origin, impact and cost of each garment to consumers. As regulators increase the requirements to back up any sustainability claims, investment in tools to gather and manage supply chain data is likely to become more widespread.

Stronger bridges should be built between companies’ technical sustainability and marketing teams to review how information can be communicated in a responsible and effective manner, ensuring that marketing messages are not created in isolation. With incoming regulation, vague marketing around sustainability is no longer just a reputational risk — it could lead to fines or even legal action.

Language that could mislead consumers — such as broad terms like “green” or “eco-friendly” — should be avoided as it could give the impression that products have positive environmental attributes. Instead, important caveats or context should be made accessible to consumers, such as specific supply chain data brands can gather to show a reduction in impact against a defined baseline. For example, France-based luxury company Kering has produced internal guidelines on sustainability communications for its staff to help avoid greenwashing-related legal issues and a consumer backlash; the guidelines advise the brands under its ownership to avoid broad, generic terms like “environmentally friendly” and instead focus on clear, unambiguous statements on metrics such as emissions reduction.

To be sure, brands will still be able to identify and talk about the sustainability issues that matter most to their consumer base amid increased scrutiny, but in doing so they must ensure their claims are backed up by robust work. When ultra-fast-fashion giant Shein launched a resale platform for American consumers in October 2022 as part of a series of efforts to combat criticism, it was called out for greenwashing; research has found that resale platforms to date typically do not help to decrease production levels, particularly for fast-fashion brands. While staying abreast of upcoming regulation, fashion leaders should seek customer feedback by, for example, monitoring net promoter scores to understand their business’s perceived sustainability progress, areas of improvement, and preferences for how and when communication is delivered. Technology and digital tools will play a critical role to ensure better traceability along the value chain, from data platforms to facilitate information gathering across all production stages to rigorous data standards to track sustainability metrics.

In 2023, new communication strategies about sustainability will be required. To move the needle, brands will also need to become more forthright about their progress and shortcomings, whether it be through public reporting or product labels. If brands do not find a responsible and effective way to talk about their sustainability journey, they may risk damaging consumers’ trust or may face compliance repercussions, thus requiring brands’ legal teams to work closely with communication colleagues.

Fashion leaders have an opportunity in 2023 to forge new rules of engagement when it comes to sustainability, from aligning company-wide marketing as well as regulatory and other disclosures to working with policymakers, industry bodies and other brands to address pain points. Communication should reflect a brand’s long-term commitment to sustainability, articulating realistic, timebound targets and progress being made towards them. Yet ultimately, brands that are best equipped to make meaningful and credible change will be those that ensure every part of their operations is doubling down on sustainability, not just talking about it.

This article first appeared in The State of Fashion 2023, an in-depth report on the global fashion industry, co-published by BoF and McKinsey & Company.