MUMBAI, India — It was one of the most memorable catwalk moments of 2019. As she sashayed down the Milan runway in Versace’s jungle print dress, Jennifer Lopez looked even more toned and confident than she did wearing the original dress two decades earlier. Hailed as a stroke of marketing genius that got millions of people talking, the last thing on anyone’s mind was: “who actually made it?”

If it weren’t for a chance encounter, no one would probably know that it was a group of artisans from Mumbai, India who had sewn the intricate embellishments on the reissued dress that helped Lopez look like an ageless Amazonian.

It is understandable that Versace didn’t publicise what would have been a mere footnote in the garment’s long Italian production log. Few expect brands to acknowledge everyone involved in the making of a garment. However, what a growing number of Indians find irritating is that the important role of Indian craft is — broadly and systematically — still brushed under the carpet by leaders of Europe’s luxury industry.

At a time when there are calls for the makers of high fashion to finally be given due credit and respect, some now believe that consumers should be told that some of the handwork seen on the world’s catwalks and red carpets passes through the deft hands of India’s most skilled embroiderers and artisans.

While cost is certainly one consideration, another is that having garments embellished in India can yield superior results.

“It’s really a no-brainer that luxury embroidery would come out of India,” says Nonita Kalra, editor-in-chief of Harper’s Bazaar India. “In India, our craftspeople make the designer. Look at the sari, it’s just nothing but nine yards of fabric. It would be nothing without the artisan making it.”

Debunking an Unfortunate Fashion Myth

Several Indian atelier exporters interviewed for this story confirmed that the cost of producing luxury embroideries in Europe would be around ten times higher than what they can produce in India.

“Today the only ones who can still afford to do their embroideries in France are Chanel and Hermès, that’s all. All the others, it’s finished,” claims Maximiliano Modesti, the founder of Les Ateliers 2M, a luxury embroidery company in Mumbai.

Some continue to misinterpret such observations to mean that the only reason embellishments are outsourced to India by Made-in-France or Made-in-Italy luxury brands is to cut costs. This, however, is an unfortunate and persistent myth that needs debunking.

While cost is certainly one consideration, another is that having garments embellished in India can yield superior results. India, with its centuries-old traditions of craft and incredibly high levels of artisanal excellence is an obvious alternative.

Karishma Swali, managing director of Chanakya says it was her Mumbai-based export atelier that did the embroidery for the Jennifer Lopez Versace dress. A representative for Versace declined to comment.

“While beautiful craft-making still exists in Europe, the numbers are fast dwindling and cannot be compared with the artisanal breadth and volume that India offers,” she says.

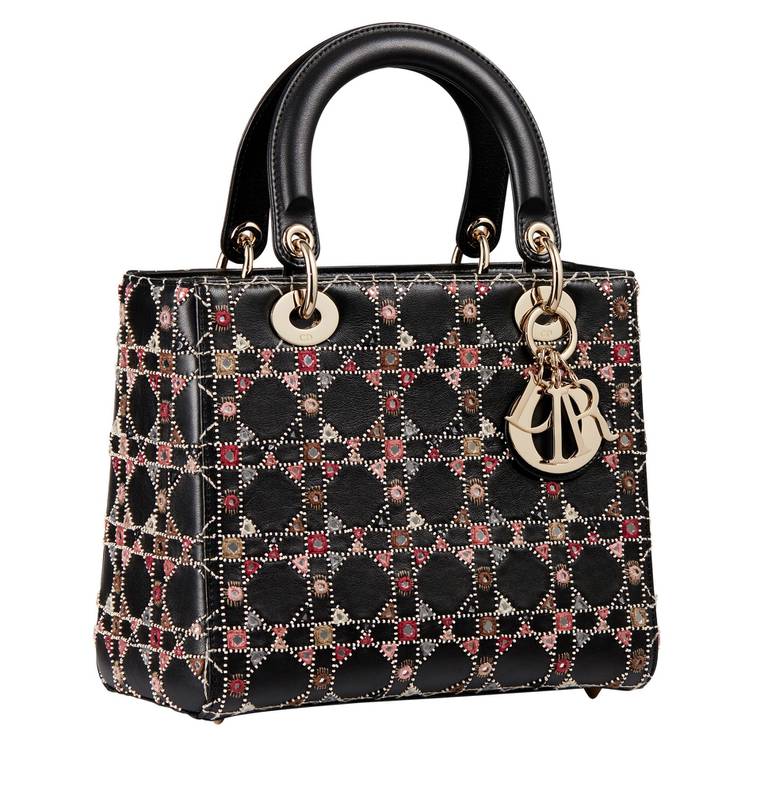

Lady Dior bag incorporating traditional Rajasthani inspired mirror work | Courtesy

More proof of India’s central role in European luxury can be seen from the iconic embroidered book clutches by Olympia Le-Tan; the lavender feathered spherical dresses at Jeremy Scott‘s Moschino show during Milan fashion week Spring/Summer 2018; and the patchwork embroidered or beaded Christian Dior saddle bags for Autumn/Winter 2018. The common denominator being that these items passed through the expert touch of highly skilled Indian embroidery artisans.

According to Swali, in addition to Dior and Versace, Chanakya also produces embroideries for brands including Saint Laurent, Balmain, Giambattista Valli, Prada, Valentino, Céline, Gucci and Loewe. Of the Versace-Lopez dress she says, “the elements used to make the embroidery were recycled PET [plastic bottle] sequins specially laser-cut in customised shapes. Working with the Versace team is always special.”

Enormous cachet is attached to the European provenance of many luxury brands, but few have gone public to reveal which parts of their production line are outsourced to craftspeople beyond Europe. Instead it is left to the Indian atelier owners to declare their famous clients and to reveal that some of the current business relationships between the fashion capitals and India have been going strong since the early 1990s.

Embroidery traditions in India represent an intoxicating mix of ancient influences drawn from silk route trading, Persian invasion, centuries of internal migration, trade with China and diverse local-cultural beliefs. Techniques such as embroidery on leather with real gold thread, or gossamer fine chikankari, are part of a vast repertoire of craft techniques still practised across India to this day.

As Carlo Capasa, president of the Camera Nazionale della Moda Italiana concedes, “embroidery, especially on silk or accessories, is in the ancient Indian tradition. This is why embroidery made in India is so popular with luxury brands.”

So if luxury industry leaders like Capasa now recognise the exquisite quality of Indian embroidery, why the big secret when brands hire these talented Indian artisans?

Unfair Stigma From a Colonial Mindset

India held a key role in the development European luxury from the 17th century onwards, but the country’s more recent reputation as a cheap exporter of garments for the fast fashion sector has come to overshadow its long, rich fashion craft history — and the diversity of its current activities in the luxury industry.

Some contemporary western designers, notably Dries Van Noten and Isabel Marant have long been open about their relationships with India, actively celebrating their work with highly skilled Indian artisans as part of their brand stories. Indian craft is an integral part of the signature of these brands and they, in turn, sustain artisanal livelihoods season after season.

This bias panders to a lingering colonial mindset that European culture and its decorative arts are somehow superior.

Prada, weighed in on the debate about crediting Indian craftsmanship with its range of Madras bags launched in 2012, which were hand woven in goat’s leather by artisans in Chennai. They were notable for the embossed leather “Made in India” label proudly displayed inside the top of the bag’s interior, but the line only lasted a few seasons.

Apart from these and a few other brand examples, a veil of secrecy has long surrounded the luxury industry’s very real and valuable connection with India. Some brands still seem to fear being seen to source craft from India in case it damages brand equity. This bias panders to a lingering colonial mindset that European culture and its decorative arts are somehow superior to those of its former colonies.

Artisans in the Chanakya atelier in Mumbai | Source: Courtesy

The reality is that India’s importance as a sourcing destination for luxury will only continue to grow — in particular, for Indian crafts like embroidery. Modesti argues that any notion of Indian craftmanship taking the shine off luxury is not only misguided and absurd but also contrary to the evidence.

“The fact is that highly skilled handwork (which can take days or even months to produce a single piece) is never something that even premium fashion brands will [ever] be able to do in terms of costs. Therefore, artisanal craft [from India is actually] one of the key ways to justify luxury brand positioning,” says Modesti.

The ways that brands now work with Indian embroidery ateliers is a reflection of the time demanded by ever more intricate, elaborate or opulent embroidery techniques.

“For example, the embroidery we do for Hermès, no one else could do. Only Hermès could use it because it’s very time consuming. It costs a lot, and it takes a lot of time so, you can’t produce high quantities and you can’t do fashion cycles.”

Enter India’s Embroidery Brokers

Modesti’s story begins in the early 1990s when he discovered a small archive of Indian embroidery in a dusty folder while finishing his MBA at IFM (Institut Français de la Mode). It fired a desire to learn more and in 1993 he set off on his first trip to India where he found highly skilled embroidery in Mumbai (then called Bombay).

Returning to Paris, Modesti worked as studio manager for couturier Azzedine Alaïa. The lightening-rod moment came one day in 1994 when Modesti was opening the day’s post in Alaïa’s studio.

Modesti recalls, “[Alaïa] had embroidered a dress with Lesage and when I opened the bill for the embroidery coming in, well I was new in that job, but I said ‘are you crazy…we’re not going to make any money!’ I said, ‘OK we’re going to do this collection fully in India because we need to find a new way to make these products affordable, and in sufficient quantities to be profitable for the company’.”

Knitwear for the Alaïa Spring/Summer 1996 collection was delicately enmeshed with black sequins sewn by artisans in Mumbai and large orders duly came in from buyers and clients around the world. A few years later, Modesti decided to return to India full time and founded Les Ateliers 2M where he says he produced work for Stella McCartney who was working for Chloé at the time — and then for her replacement Phoebe Philo.

Gayatri Khanna Sabharwal, who founded Milaaya in 2000, is another veteran of the luxury export embroidery business. She started at Saks Fifth Avenue in New York as a buyer for designer wear. Selling accessories like pashmina shawls on the side, a lightbulb moment came when one day a client asked for some embroidery on a garment.

“That’s how I thought of Milaaya Embroideries. At first, I worked with a supplier in Mumbai as I was in New York City; then I set up a small atelier with 20 artisans in Mumbai – and [it] kept growing.”

Sabharwal says she gained her first clients — including Ralph Lauren and Cynthia Rowley — by “walking all of 7th Avenue in New York, picking up business cards for large and small fashion brands and making appointments.”

Artisans in the Chanakya atelier in Mumbai | Source: Courtesy

Karishma Swali, who runs Chanakya with her sister-in-law and brother, recalls it was her father Vinod Shah who set up the export business in 1986, his first clients being Fendi and Alberta Ferretti. Previously, Shah had travelled the world working for the textile arm of the Indian multinational Tata, gaining influential contacts along the way.

In preparation for joining the family business, Swali and her brother worked in Italy with Ferretti, focusing on pattern making, draping and quality assurance “to absorb the Italian eye for attention to detail and perfection.” On returning to Mumbai, they also brought Italian and German technicians into the company.

High Tech Ateliers Doing a Roaring Trade

Chanakya’s atelier now runs like the proverbial well-oiled machine: its large modern offices in Mumbai are home to teams of designers dedicated to the complex process of engineering hand embroidery in unison. Some are permanently dedicated to working on a large client’s collections, akin to off-shore design teams.

“Our research and innovation timelines are very quick on account of large experienced design and merchandising teams. We make all artworks and artistic sketches in-house as we have all the computer aided design tools and hand sketching artists necessary for these,” Swali explains, emphasising the importance of their digitally logged archives which includes over 100,000 archived samples.

Chanakya has a close working relationship with Maria Grazia Chiuri, who the atelier first encountered when Chiuri worked as a designer in the accessories department at Fendi. The relationship continued when Chiuri moved to Valentino, and now Swali says they collaborate closely for Dior.

Swali reflects on the atelier’s design process which begins with research, inspiration and moods to create a collection. “They provide a silhouette or a pattern to work with [and] they pick ideas and techniques that they’d like and then we fine tune them together. The first prototypes come out of that,” she explains.

Artisans in the Chanakya atelier in Mumbai | Source: Courtesy

Indeed, it is the ability of Indian ateliers to create highly specialised and customised designs in real time that drives a core part of such businesses. This is equally true for Aditiany, whose New York offices house an archive of thousands of exquisite embroidery samples made over the years.

Naina Shah’s mother founded the company in 1991 with just six artisans in Mumbai (they now work with 80 in-house). According to Shah, who took over the running of Aditiany as vice president ten years ago, the first designers Aditiany worked with included Ralph Lauren, Michael Kors, Giorgio Armani, Valentino and Alexander McQueen.

While India’s embroidery brokers tend to be tight-lipped about their finances and profit margins, industry insiders believe that the business model can be very lucrative. Milaaya’s Sabarwal, who cites Dolce & Gabbana and Alice + Olivia as clients, says competition is getting fiercer in the sector, with more Indian export ateliers opening up in recent years.

Collectively, the sector will also come under increased scrutiny about sustainability, fair wages, working conditions and other ethical considerations now that transparency is an increasingly important part of supply chain management.

Many of India’s high-end embroidery exporters have showrooms and offices in the US, Italy and France. Modesti however, prefers his clients to come to India and sit with the artisans to truly understand their techniques and feed this back into the design process.

For example, he says, “embroidery on leather is a specialist technique that Indian artisans have mastered, so there’s no other place in the world you could hand paint with a needle on leather.”

He adds, “the finesse of what they’re doing, it’s almost like a painting. Where else can you do that but India?”

Dr Phyllida Jay is the author of Fashion India.

Related Articles:

[ India, the Fashion World’s Next Manufacturing Powerhouse? ]

[ A Humble Fabric Helped India Fight British Rule. Now It’s Big Business. ]