In the spring of 1985, an American sports fan could pick up a new pair of Nike Air Jordan 1s for $65. Fast-forward to the present and, this week, a pair of those same Jordans have garnered a $1.8m (£1.45m) bid at auction.

Those numbers don’t just speak to a meteoric rise of the Nike brand as a sportswear powerhouse now valued at more than £26bn; they also illustrate the cultural cachet that a pair of trainers can hold, shoes whose influence today extends far beyond the white-painted lines of the basketball court and into the world of music, fashion and even politics.

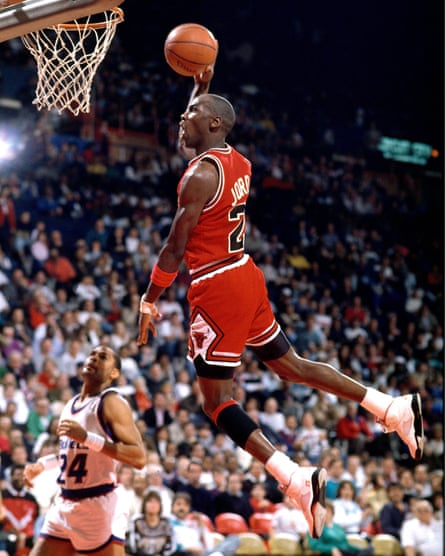

The Air Jordan brand was launched as a collaboration with Michael Jordan – the best basketball player of his generation – and is immediately recognisable by the silhouetted image of Jordan in mid-flight, the “Jumpman” logo.

But whereas Air Jordans were originally designed to be signifiers of sporting success, they’re now loved and worn by “winners” across different industries and continents.

The superstar rapper Drake didn’t just name a song Jumpman in honour of his favourite shoes – he ordered a solid gold model of them for a reported $2m. And when the biggest names in football, Kylian Mbappé, Neymar and Lionel Messi, turn out for Paris Saint-Germain, their jerseys aren’t emblazoned with a football logo; it’s the Jordan silhouette that adorns their shirts.

The cultural significance of the brand was evident when the movie director and civil rights activist Spike Lee visited the White House in 2012 to meet America’s first black president, Barack Obama. His gift to the commander-in-chief? A brand new pair of white Air Jordans for the man who had climbed higher than any politician of colour in America’s history.

The shoes are so ubiquitous in US pop culture that Jordans could be placed in a bracket alongside American design classics such as the Model T Ford, but the story of Nike before Air Jordan was not always so illustrious. The pre-Jordan days are pored over in Air, a new film about the game-changing 1984 deal between Nike and Jordan. The film, which is directed by Ben Affleck and largely takes place in Nike’s headquarters in Portland, Oregon, is set in 1984, when Nike attempted to sign Jordan, then a rising college basketball player.

At the time, Nike’s sales were down 29%; it lacked cultural prestige, particularly in comparison with Adidas, which at the time had 50% more revenue, and was worn by the chart-topping hip-hop stars Run DMC. Jordan had wanted to sign with Adidas – and the film shows Nike’s executives persuading him otherwise by creating the Air Jordan trainer.

That shoe would go on to transform Nike’s fortunes: the company sold $100m worth of trainers and clothing in 1986 alone. And the Air Jordan became central to what is known as “sneakerhead culture”, with the rarest iterations selling for more than a million dollars at auction. In 2021, the Jordan brand revenue hit $4.8bn.

Like many people born in the 1980s or later, the film’s costume designer, Charlese Antoinette Jones, was surprised to learn that Nike had lacked much status before the deal. “I can’t remember a time when Nike wasn’t cool,” she says. “It was interesting to discover that window of time. To play and to imagine a world where Nike wasn’t cool, and to ask, ‘What would that look like? How could I show that in the corporate culture – how nerdy would it be?’”

Basing on research from photographs of the Nike team, late 1970s and early 1980s copies of Life magazine and JCPenney’s shopping catalogues, the aesthetic within Nike’s offices in Portland, Oregon, is earth-toned, and centres on the idea of Nike as “a scrappy up-and-coming startup”. Few staff have matching suits; the fit of many items, including a smattering of oversized jumpers and blazers in crowd scenes, is a bit “off” in order to feel “relatable and scrappy – no one in the office is pristine and perfect”. In the juxtaposition of power with scruffiness, the Nike executives resemble precursors to the hoody-wearing chief executives of Silicon Valley in the 2010s.

The costumes brilliantly underline the movie’s central argument: that Nike’s current, heady levels of style credibility did not exist before the deal with Michael Jordan. As Elizabeth Semmelhack, the director of the Bata Shoe Museum in Toronto, and curator of the influential 2015 Out the Box: the Rise of Sneaker Culture exhibition, points out, it wasn’t that Nike had not been successful before that. The brand successfully captured “that very 1970s moment of jogging and marathon running”, an aesthetic encapsulated by the 1976 campaign shot of Farrah Fawcett skateboarding in Nike Cortez trainers.

But when culture shifted, and even white corporate America slowly became aware of the economic and cultural importance of the intertwining cultures of basketball, breakdancing and hip-hop led by African Americans (largely in New York City), and especially through sneakers, Nike lagged behind. Nike was sometimes present in photographs of breakdancers from the period, says Semmelhack, “but they certainly were not in the vanguard”.

Though Nike was not officially involved with the movie, the company will be happy with its portrayal, positioned at the centre of the hero’s journey. Adidas, however, may not be quite as thrilled with jokes in the script about its founder, Adolf Dassler’s, membership of the Hitler Youth making the final edit.

Nike, meanwhile, is now the world’s biggest sports apparel company, with 2022 sales of around $46.7bn. Its tentacles have spread so far that it is difficult to imagine the modern cultural landscape untouched by the Jumpman brand. This week, six individual Air Jordan sneakers – each one worn by Michael Jordan during NBA championships in the 1990s – are on auction at Sotheby’s. Already one has attracted the record-breaking bid. Even if the white, middle-aged men in polo necks in Nike’s headquarters did not have style credibility back then, the sneakers they created have a life of their own.