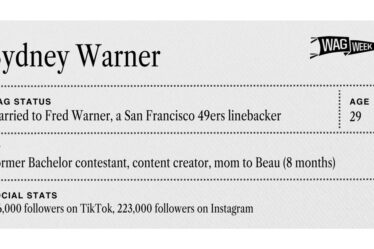

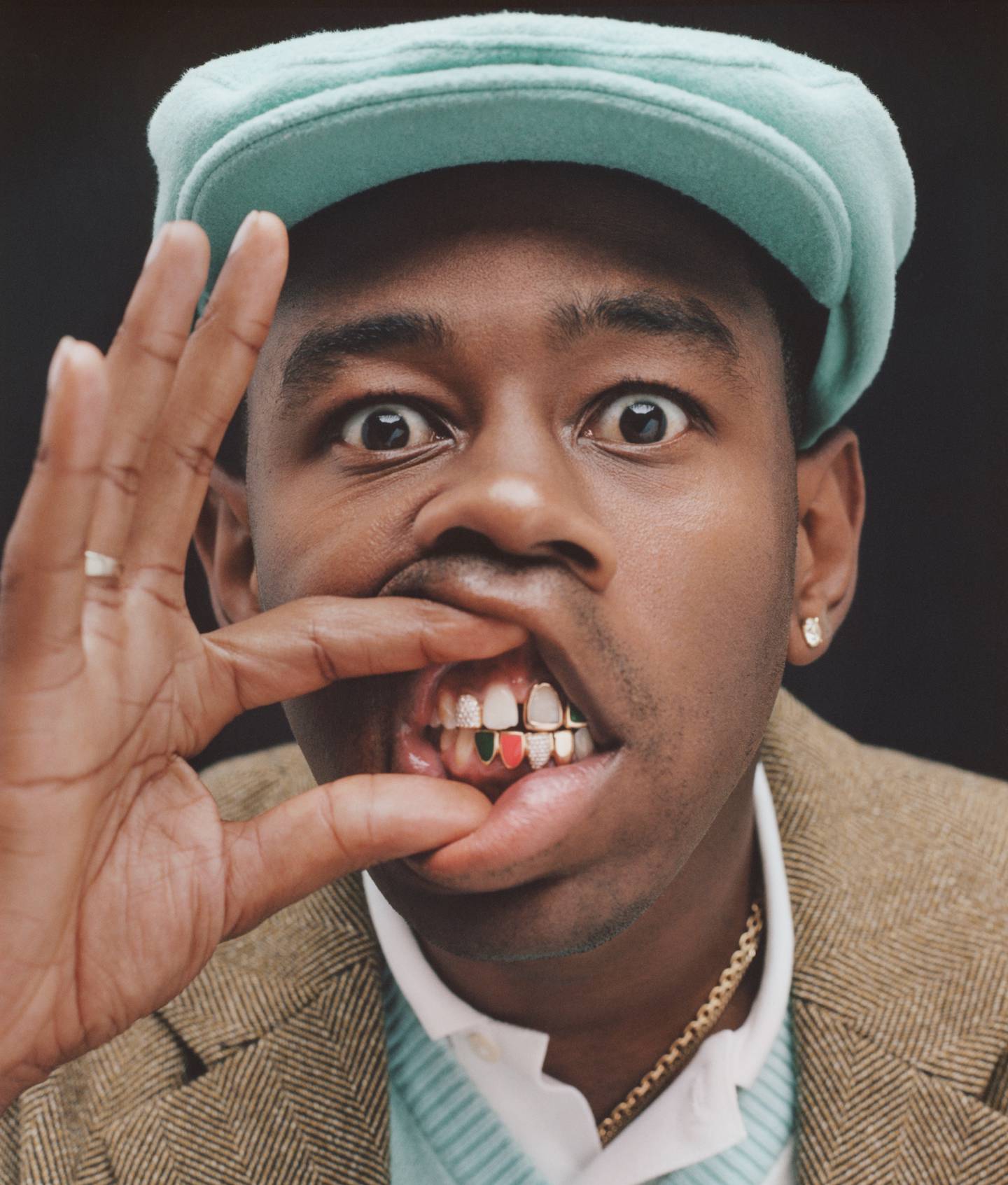

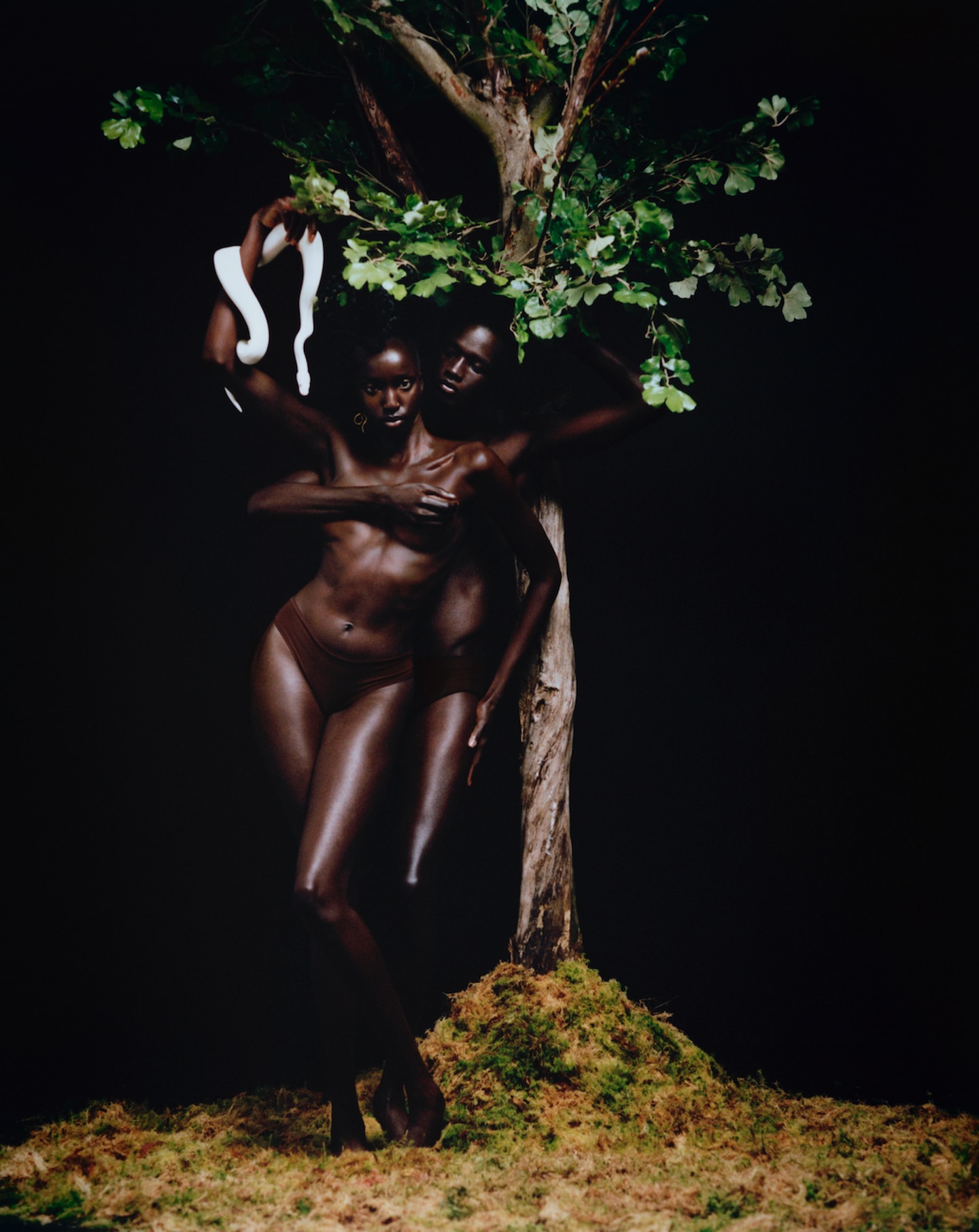

In 2019, Campbell Addy photographed Adut Akech for i-D magazine. In one striking, starkly pared-back image, Akech is seen crouching on an ottoman in a Richard Quinn bodysuit — a deep Black figure against an off-white background. The scene would be mute were it not for the model’s gaze piercing out of the dark silhouette, a jolt of life that bestows it with the power of a Kerry James Marshall painting. (Addy was in fact inspired by the American photographer Lorna Simpson, whose images he deconstructed in preparation for the shoot.) Even though the particular image of Akech was cut from the editorial, Addy considers it some of his best work.

This single picture — and the intense research, focus and on-set wizardry behind it — offers a potent key to understanding Addy’s emergence as one of the most lauded imagemakers of his generation. Since graduating from Central Saint Martins in 2016, the British-Ghanaian photographer’s work has been exhibited internationally and appeared in British Vogue, Time and WSJ, among other titles. Invariably, Addy portrays his subjects – who are often Black – as enhanced and yet authentic versions of themselves: raw, vibrant, and at once luscious and crisp, dripping with emotion and character.

Addy’s latest solo exhibition, ‘I Love Campbell,’ opens today at 180 Studios in London. Neither a retrospective nor a fashion exhibit, the art show marks a crossroads in his young career. “A lot of change happened in my life last year. I felt stagnant, wanting to explore new mediums. So, I decided to do a show with work that might not be what people expect of me, but which contains ideas and themes essential to who I am,” says the 30 year old, who is candid about his mental health struggles and perennially concerned with being true to himself. Many of the 36 works in the exhibition, which includes mixed-media images and photographs, haven’t been seen before.

Long before he picked up a camera, Addy used pencils to express himself, “My mother always encouraged us to draw — graphite sticks didn’t cost much.” Still, he never dreamt he might one day become a celebrated artist. “That wasn’t attainable for someone of my background.” Addy recalls his upbringing in a South London family as joyful and nurturing of his creative instincts. “My mother was young, and I would watch her experimenting with style. Even though we didn’t have much, there was always room for self-expression.”

Things changed when Addy’s mother discovered his sexuality. “It was a religious African household, so her way to deal with me being gay was to send me away to ‘protect’ me. I don’t condone it, but I understand it now.” Addy ended up homeless and in foster care, though he calls it “the best thing that ever happened” to him. “It was traumatic, but I met some of my best friends and had to fend for myself at 16 years old, which taught me great work ethic. I betted on myself at a young age, and it seems to be paying off.”

It was art he could relate to, along with his imagination, that helped Addy survive. “I would bunk school and go to an art gallery instead of the park like other kids.” He recalls the impact of seeing artist Chris Ofili’s ‘No Woman, No Cry’ when he was 15 years old. “It was the first time I saw Blackness in a painting by another Black person. As a kid who had no choice but to use unorthodox materials because it’s all I had access to, seeing the way Ofili used resin and cow dung was an epiphany.” Addy started recreating Ofili’s work, replacing the faces in it with his own likeness. “I couldn’t afford colour, in my drawings shades of gray stood in for different skin tones.”

True to his time, Addy was influenced by advertising as much as art, “I am a child of the 1990s, I grew up in the era of commerce. The first fashion image I vividly remember seeing was at Milan airport. We had missed our flight and there was a huge Armani billboard. It was giving Michael and Janet Jackson’s Scream, with a male figure jumping out of a silvery background. I remember sneaking into the store at the terminal to steal the magazine just so I could keep looking at that advert, which I kept for years. That image took me out of a long frustrating layover and made me realize I could fantasise, which was powerful. It planted the seed for my love of creating stories.”

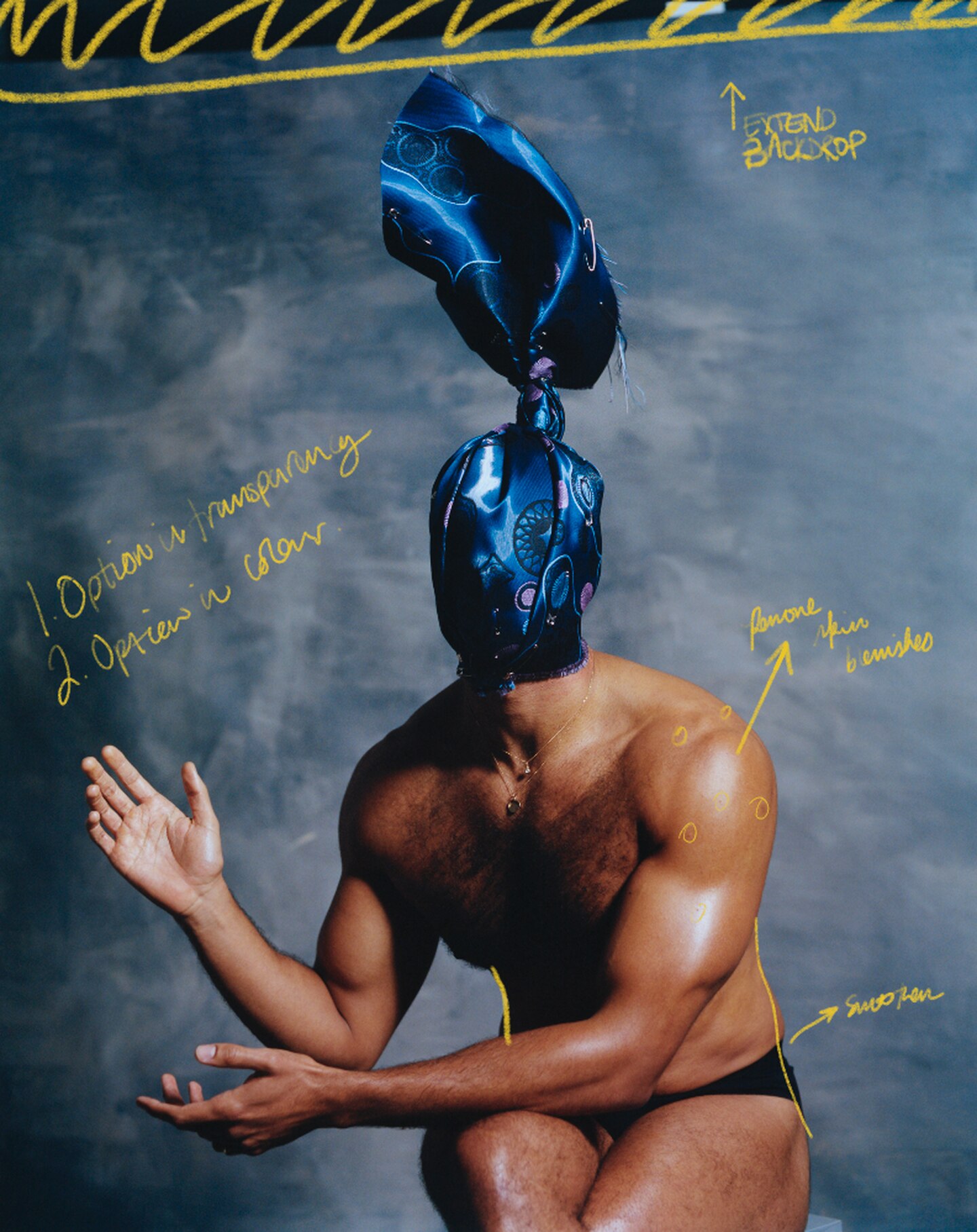

While Addy says he will always be torn between various media, at age 18, he chose to pursue a career in fashion photography. “I decided to learn the classics, then do a Nick Knight, and lastly infuse it with my own modernity and see what Campbell Addy would want to do.” Before receiving any formal training, Addy gleaned the secrets of his craft from its masters: “Richard Avedon was the first photographer I hyper-focused on. I stared at his images forever, trying to unlock his ability to capture a timeless moment, he was a trickster. Irving Penn’s nudes made me emotional — he saw the beauty of the human form with such sensitivity, he genuinely cared about the women he photographed. Then when I discovered Nick Knight, it hit me, ‘Wow, what can’t I do? I can do anything.’ I loved how freely Knight collaborated and used other mediums.”

Among his many mentors, Addy feels especially indebted to his A-level art teacher (“I still hear Miss Tomic’s voice, ‘Go bigger! Don’t be precious! Make art that reflects who you are!”) and Claire Robertson, one of his professors at Saint Martins (“She taught me to focus less on how I was going to print and think more of the image I was creating.”)

The older I get and the more I lean into myself, the more I find solace in my community.

Today the encouragement that keeps Addy going is more likely to come from the likes of Edward Enninful — who wrote the foreword for his first book, published in 2022 — and Naomi Campbell. The supermodel recently called him to tell him her gazelle-like portrait on the cover of Vogue India’s latest issue, shot by Addy, is one of her favourite images of herself in 30-plus years. For his part, Addy recalls the shoot as particularly challenging, “It was about moving Naomi’s chin by a fraction of an inch. All had to be succinct, statuesque and sculptural, like in her early work.”

Precision is typical for Addy, who shows up on set with a thought-out concept for the images he envisions and often mines his own experience as a queer man from Croydon to compose them. “I arrive with a character and storyline that fits the subject in mind. But there is always a little bit of me present in my work, regardless of who I am shooting. My ideas derive from my history, be it a religious moment or someone I met on the street. I’m constantly writing down things. All my pictures start with words, then I anchor it, ‘What am I saying? Is it urgent? How authentic is it to me?’ In my early years I wanted so badly to be whatever it was, not realising you are it; everyone is it. The older I get and the more I lean into myself, the more I find solace in my community.”

Queerness extends beyond one’s sexuality, it can also be a form of expression.

If Addy is often credited for showcasing underrepresented identities in his work, he interprets queerness broadly, “Growing up as a queer person I often had to hide my genuine interests. In that, queerness exists in all of my work because it contains all of my hidden gems and uncool ideas. I would never have dared to call someone to watch a David Attenborough documentary with me, even though it’s what I loved, but now it’s in my work for everyone to see [a recent WSJ menswear editorial featuring the model Goy Michael was inspired by an Attenborough film on birds Addy loves]. Just to survive as queer people we have to see and approach things differently. Queerness extends beyond one’s sexuality, it can also be a form of expression.”

Addy — who also writes poetry and creates set designs and films, among other vocations — says, in the autumn, he plans to revive Nii Journal, the culture publication he founded as a student. He also aims to continue his photojournalism projects, which keep his eye sharp and inform his commercial work. “When shooting youth culture in Ghana or South Korea, I always have to be looking; it’s not planned the way a fashion image is. That forces me to follow my instincts, the picture could be anywhere and has to happen in a second.” And since hitting a creative block in 2021, Addy has been painting a lot more, “It’s a habit now, I’m addicted.” Fittingly, two new paintings are on display in ‘I Love Campbell.’