It is the 50th anniversary of Bruce Oldfield’s couture business this year, and he marks it with one of his greatest accomplishments – even if it comes with a certain amount of awkwardness. News broke in February that Oldfield was designing Queen Camilla’s, dress for the coronation. Such a historic commission would be a crowning achievement for any designer. For someone from Oldfield’s background – pretty much the opposite end of the social spectrum from royalty – it is almost miraculous.

The awkwardness comes because the Camilla commission immediately triggers comparison with another of Oldfield’s royal patrons (and King Charles’s wives, for that matter): Diana, Princess of Wales. In their shared 1980s heyday, Diana was one of a number of high-profile women who helped make Oldfield’s name. And as with many of Oldfield’s clients, it seems, the two were also friends.

We meet at his modernist riverside flat in Battersea, London. On a table in the living room sits a framed photograph of Oldfield in 1985, with Diana, Joan Collins and Charlotte Rampling (all three wearing his dresses, naturally). Inches away is a signed photograph of Camilla from 2011. “I’ve been designing for her for 13 years,” he says. “So for more years than I did for Diana, actually.”

Of course, he says, he’s sworn to secrecy about Camilla’s coronation dress. But he’s happy to talk about their first meeting. “There was some kind of formal do at Clarence House [Charles and Camilla’s London residence]. It was the time when she’d fallen down in Scotland and sprained her ankle. So because she couldn’t walk around, she sat in a chair, and they put half a dozen chairs around her, and her stewards brought five or six people at a time to sit and talk to her. But they brought me on my own. And she said: ‘Now, Bruce, I think it’s time that we actually made a few dresses, don’t you?’” He has designed formal wear for Camilla on many occasions since, including a silver-embroidered top and skirt she wore on her first state visit in March. He once said: “I gave Diana her glamour and Camilla her confidence.” Speaking of the two women in the same breath, or even the same interview, makes Oldfield visibly uncomfortable, though. “Let’s not do it,” he says gently.

Tact, as well as talent, seems to be a component of Oldfield’s enduring success. And as well as his flattering designs, one of the reasons clients keep coming back is Oldfield’s easy manner: polite and decorous but relaxed and informal, with a touch of mischief. “I get on well with people; I find I can get them,” he says. “I’ve been doing this for so long, I guess that people are expecting something slightly different from me, someone very arrogant, I suppose. But I’m much more pragmatic, down to earth, call a spade a spade.”

Oldfield, 72, titled his 2004 autobiography Rootless. He is one of those people who seems to have had no fixed position in society and never really fit into any category: class, race, even sexuality. Perhaps this explains his ability to get along with everyone.

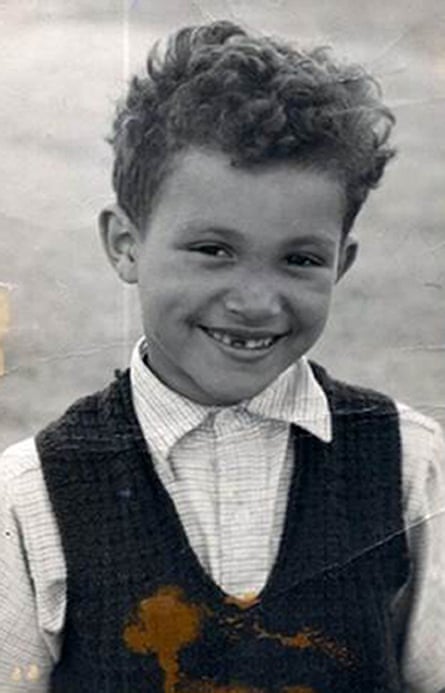

He never knew his birth parents, and would not find out who they were until he was in his 30s. “I was taken by Barnardo’s straight away. My mother was considered not capable of looking after a child,” he explains. His mother was a white British woman; his father a Jamaican man with whom she had had a casual affair (while she was married to another man). The closest Oldfield had to a parent was an experienced foster carer named Violet Masters, who took him into her household in Durham when he was three.

Oldfield describes his childhood as “dirt poor”: an outside toilet; newspaper cut into squares for toilet paper; no phone or fridge or hot water, weekly baths in a tin tub filled in the kitchen. They later moved to a slightly nicer house, right beside the A1. “We lost a few dogs who put their head out too far when a lorry went past.”

He grew up as one of five foster children Masters took in: three boys and two girls, all children of colour. He became close to his foster siblings, but is more measured in his affections for Masters. “We never called her mum,” he says. “She was never nasty to us, and as far as I’m concerned, we were being treated in exactly the same way as the neighbours or anybody else.” But it never really felt like home, he says. “She tried.”

At least Masters, a skilled dressmaker, introduced Oldfield to his future trade. She made clothes for private clients and her own children – whom she also encouraged to sew. Oldfield, in particular, took to it. He recalls making dresses for his sister’s dolls – inspired by the Ginger Rogers musicals he would watch on TV. A Barnardo’s report from the time noted that he was very observant of other people’s clothes and “had an effeminate streak”.

Oldfield never really questioned why Masters only took in children of colour. “We were never sat down and had it explained to us, ‘You’re slightly different,’” he says. “Later on I thought that it was the money, because not many people wanted Black children, let’s face it.” Despite being the only people of colour in the village and at school, there were only a few times Oldfield was made to feel different, he says. When he and his brothers were dressed in black balaclavas for the school “black and white minstrel” play, for instance. Or when he was about 10, watching the Durham Miners’ Gala street parade. “This woman came over and whacked our foster mother on the arse with a stick and said: ‘My Jesus told me to get these children back to where they came from.’”

Oldfield was bright. He was one of the first Barnardo’s children to go to grammar school. Then, aged 13, he left Masters’ home to live in a Barnardo’s branch home in Ripon, Yorkshire. His childhood was not unhappy but nor was it particularly secure, it seems. “There was always this thing of being slightly at the whim of somebody else, and that it could change like that.” He snaps his fingers. “So when I was in the branch home, they’d say: ‘If you don’t behave yourself we will make you a ward of court.’ And with our foster mother, there was always a bossy, nosy welfare officer coming along to judge you and evaluate the situation of the home environment.”

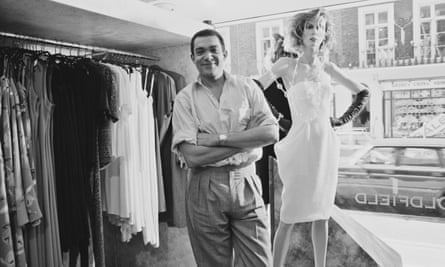

It was only when Oldfield went to art school in London – after an abortive attempt to train as a teacher – that he really began to take control of his own life. He began at Ravensbourne College, then charmed his way into Central Saint Martins school of art to study fashion design. Those childhood years obsessing over sewing paid off: he was ahead of his peers and knew exactly what he needed to learn and what he wanted to make. He developed a particular interest in smocking – a technique whereby fabric is folded and gathered in a sculptural way around a dressmaker’s dummy, then stitched in place, as opposed to designing a garment “on the flat” with two-dimensional patterns. He still designs like that to this day. Standing next to him is a dummy half-draped in plain toile – a mock-up for a dress he is working on. “It’s very complicated. But the idea is, at the end of it, it looks quite simple.”

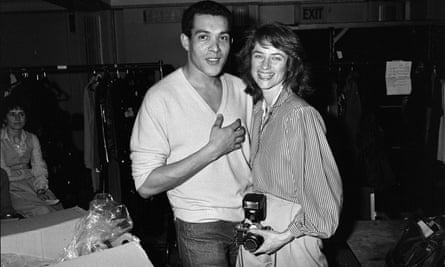

It was now the early 1970s and Oldfield had his finger on the pulse of modern fashion. “I was confident. And I wanted success. And I got it quickly,” he says. He had also grown into a tall, handsome young man. “I was just really coming out of my shell, wasn’t I? Well, I was coming out of everything,” he laughs. “I got all the girls. I didn’t know that I didn’t want the girls, but I got them all anyway.” He is not secretive about being more attracted to men, but he never felt the need to define his sexuality. “And I still don’t. I’ve said it, but I don’t proclaim it.”

By the same token, Oldfield never really defined himself racially. “When this interview was posited [for the Guardian’s Black lives strand], I sort of thought: ‘I’ve never felt myself to be a Black man.’” How would he describe himself? “I’m a brown man. I mean, it would be ridiculous to call me Black. The only time I’m Black is when I spend a week in the sun.” He’s being slightly flippant, he knows. “I’ve never ever been in a situation where I’ve immersed myself deliberately or accidentally in Black culture. It just has never been my thing. Only the music.”

Oldfield’s talent was spotted early. He had commissions to design for Revlon and Liberty’s even before he graduated. His first celebrity client was Bianca Jagger, who had attended one of his student shows at Central Saint Martins. She had a suit she wanted altering that had once belonged to Rita Hayworth. Oldfield remembers visiting her house in Chelsea in 1973. “She appeared at the top of the stairs in a satin dressing gown. She was in the first-floor room. It had venetian blinds down to the ground and light pouring through. It was like a black-and-white movie. I wasn’t intimidated, though.”

Soon after, in September 1973, he was invited to New York to design a collection for the department store Henri Bendel. The job only lasted a season but it opened Oldfield’s eyes, especially about race. “I suddenly found myself in this situation where there were lots of Black young people my age who were graphic designers, fashion designers, photographers, models, people in the creative industries and who were out dancing at night. And they were straight and they were gay. And there were women and there were men.” London was years behind, he says, shuddering at the thought of British gay bars of the era.

New York was shortly followed by a stint in Paris, where he hung out with “fashion It girls” such as Jerry Hall, Marie Helvin and Tina Chow. Apart from Hall, all of them were mixed race. “We were seen as exotic. Our non-whiteness was very attractive.”

By the 1980s, his brand had become associated with the height of glamour, worn by models, movie stars and high society: Rampling, Collins, Jane Seymour, Faye Dunaway, Barbra Streisand. Many of them became friends. The Diana connection began in 1981 with “a very sharp rust wool Venetian suit” he made as a kind of pitch to the newlywed princess, whose dressers were calling in samples from various designers. Diana wore it when she turned on the Regent Street Christmas lights that year. There was no inkling at this stage she would become a global fashion icon, but she became a regular patron.

She and Oldfield were “sort of pushed together” after Diana became president of Barnardo’s in 1984. Oldfield had always been a supporter. That year he arranged a lavish fundraiser, with a dinner and charity fashion auction, which Diana attended, alongside a host of stars. He could not have asked for a better brand ambassador. Over the next 10 years Diana was regularly seen wearing Oldfield’s dresses, at red-carpet occasions and state visits to the US and Australia. Oldfield was something of a celebrity himself by this stage, appearing on chatshows and in gossip columns.

He must have felt as if he’d made it. “I did, but business was always very tricky, because we never had any finance.” Expanding a brand to the scale of a Chanel or a Dior requires huge investment, he explains. “You can’t afford to do that without backing. And you certainly can’t afford it unless you’re selling really cheap clothes in huge quantities, which are probably made in China or India or wherever.” By contrast, Oldfield keeps his operation small and high-end. He has never advertised and he doesn’t do catwalk shows – it’s all down to word of mouth (and better celebrity endorsement than money could buy). He recently closed down his long-established shop in Knightsbridge, which he also lived above for 27 years. Today he does couture by appointment via his website, and runs a small studio in Battersea.

He is still doing fine, though, he says. “I’m not touting for work. Now it tends to be the mothers of the brides as much as the brides. And they’re younger than me, for Christ’s sake.” High society and international royals still make up a portion of his clientele. And a new generation of stars, including Taylor Swift and Rihanna, have been seen wearing vintage Oldfield. At the same time, Oldfield has kept things interesting, even collaborating with McDonald’s to design a new uniform in 2008. “I don’t even call what I do fashion,” he says. “I certainly don’t agree with or understand or embrace the notion that something is only relevant for six months, until the next collection is out. It’s just ridiculous.”

Oldfield is no longer a fixture on the social scene and he’s fine with that, he says. “I’m quite hermit-like, as I get older. I’ve had quite a lot of illness, so I’m rather surprised that I’m still here.” He laments the deaths of numerous close friends and associates over the years, many as a result of the Aids epidemic. “It’s things like that that make you very practical. If I die, I die. There’s nothing much I can do about it. Well, maybe look after myself a bit better than I was doing in my 20s, when I think of the things I used to get up to,” he says with a mischievous grin. “But I’m lucky. I’m a very lucky person.”