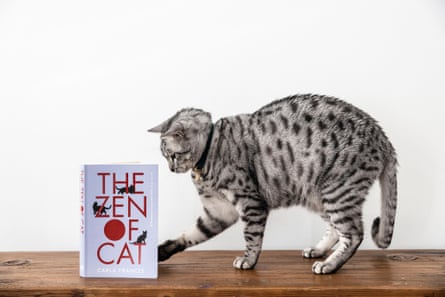

Ryō, an Egyptian Mau, is languid in a shaft of sunlight on Carla Francis’s couch, head tucked towards front paws, silver spotted fur gleaming, low thrumming purr. This, you see, is the epitome of seijaku, a Japanese word describing the stillness, silence and serenity found amid life’s chaos or, if you’re dedicated to the practice of one form of mediation or another, in your mind. “All of us need seijaku in today’s world and I think we don’t find it,” says Francis.

Across the incense-fragrant living room of Francis’s inner-Sydney apartment, Backer, a street cat, a rescue, is delicately lapping from a water fountain. Backer eschews the Japanese concept of bimbōshō which translates as “miserly nature” but which more generally describes those who have a pessimistic outlook on life, a glass half-empty approach. For Backer, life is always deliciously half full. Fresh filtered water, a stream of sunshine, a bowl of tuna, a warm lap and a scratch behind the ear. What more could any creature possibly want? “What’s there to be negative about?” Francis says.

I think of my bimbōshō dog at home, the needy assault that will greet me on my return, the longing, pleading eyes, the nothing-is-ever-enough attitude (never enough walks, treats, ball throws, beach jaunts, stomach rubs) and briefly question my choice of animal.

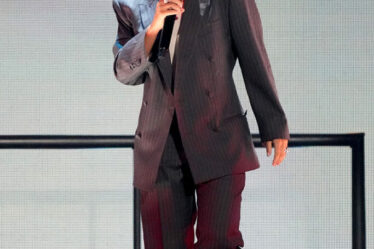

Francis, the author of The Zen of Cat: An A-Z of Japanese Feline Philosophy, might understand my dog’s greedy bimbōshō psyche. “I think I’m always coming from a place of feeling that there’s something missing in my life,” she says. Petite, reserved and wearing a black blouse with a Japanese pattern of cranes and flowers, she pours cups of green tea from a fine sea-green Japanese teapot with a bamboo handle.

Through the prism of Japanese cat stories, history, culture and spirituality, the book traverses concepts including annei (peace and tranquillity), mottainai (regret over waste), oubaitōri (never comparing oneself to others), seijaku and, of course, bimbōshō.

The Zen of Cat sprang from Francis’s love for Japan, where she lived with her photographer partner, Roland, for four years, for eastern philosophy and traditions, for cats and, perhaps most significantly, her need to address issues arising from a difficult childhood in England.

Francis grew up as the only child of a mother with serious mental health issues who died when she was 14. Her father remarried and was largely absent. She was brought up by grandparents and spent time in foster care. By the age of 15 she was living in sheltered accommodation by herself.

Animals were a source of comfort. “My aunt had riding stables in Surrey and my gran had a yorkshire terrier called Oscar. I had rescue cats. So I was surrounded by animals in a very kind of dysfunctional family. They were always my support,” says Francis, who is also the author of Travelling with Pets on the East Coast of Australia, now in its sixth edition.

“I never feel alone when I’m around animals. They know when I’m feeling sensitive or emotional. They’re probably like the brothers and sisters I never had, that I wish I’d had to go through those difficult times together.”

For some years through early adulthood, Francis was in housing situations that did not allow her to keep a pet. But when she and Roland moved to Japan in 2005 to teach English at a school in Takayama in the Japanese alps, they inherited two cats with their apartment. Ikko and Niko, garden-variety grey street cats, made them feel at home instantly. Some months later, they found a silver tabby outside a Buddhist temple and brought him home. They tried to locate his owner, without luck. “We ended up keeping him, just fell in love with him, and that was Gershwin.”

The Zen of Cat is dedicated to Gershwin, a “very special cat” – he travelled in Japan with the couple and when they returned to live in Australia he came too. (Gershwin’s last life expired in 2015.)

The inspiration for the book hit Francis when she contributed an article – “Five life lessons from a Japanese rescue cat” – to an English blog run by a London cat cafe, Lady Dinah’s Cat Emporium. As she wrote, she realised that the lessons cats could offer harried humans were infinite. “Cats are like mini teachers or mini gurus.”

While researching the book, Francis took an online course in feline psychology developed by a cat behaviourist. And, even though she was already aware of the revered place cats have in Japanese society and culture (hello, Hello Kitty!), her research led her to new discoveries, a chronology of cat obsession.

There are references in the 1,000-year-old Pillow Book, written by a lady of the royal court during the Heian period, to cats of the court. Natsume Sōseki’s satirical early 20th century novel, I Am a Cat, skewering middle-class society through the eyes of a cat, is considered a classic.

Cats populate social media and pop culture in Japan: say, Doraemon, a cartoon cat, robotic and earless, who travels back in time from the 22nd century; or Maru, the internet celebrity cat, who has been viewed on YouTube more than 535m times.

Cat cafes are sprinkled through Japanese cities. There, people who can’t keep pets in their apartments can hang out with the animals. Francis likes one in Tokyo’s Asakusa district, which is several stories up in a nondescript building which keeps cats rescued from near the Fukushima nuclear zone.

As Ryō jumps on to the coffee table in front of us and flicks his tail elegantly towards the teapot, Francis explains how knitting together cat behaviour and concepts such as bimbōshō have helped her. “When I’m constantly on my Instagram, I look at them and they’re a constant reminder to enjoy every moment.”

The couple lives on a major road and Francis says that when Backer first arrived, he would sit and gaze out the window at the traffic. She imagined him saying: “Why are they rushing, why are they rushing?”

“And I was like, ‘yeah, you’re right, why are we in such a rush all of the time?”

When she catches herself catastrophising or thinking negatively, she now knows to pause, look at her cats and interrogate herself. She asks herself what evidence she has that things might be worse than she thinks. “And the past has gone, finished. Let it go.” Cats don’t waste time thinking about the past.