My reunion with my father, after our long estrangement, happened accidentally on purpose. Our paths crossed at a family wedding, the place where grudges are often forged and dissolved.

I attended a casual gathering before the big day and there my eye fell upon my dad who, with his supersized personality, had always lived as a giant in my memory. I was surprised by his senior-citizen hair and general bodily mileage. I was deep into my 30s by then, it had been 20 years, and maybe I also looked diminished, weathered, tired from the long flight. He wore a velvet blazer and a maroon silk shirt, his usual sartorial flamboyance. He had the same smile – the genuine, happy one reserved for frothy social events.

A vacant chair materialised next to him, so I sat down. I felt terribly nervous, but my dad turned on the lighthouse of charm. He poured me a politely tiny glass of wine, which I didn’t really want, but I knocked it back anyway for courage. Then he asked me a question, light and neutral, as if he were pleased to meet me for the first time. How were my travels, he wondered.

My travels were fine, I replied. I understood, with a dose of relief, that a choice had been made on the spot. We’d agree to leave the past behind, at least for now, to go forward without acrimony or perhaps even memory, those two things being inextricably intertwined. This is where we began again, on the patched bridge of our former life, one that had been built from unusual, I could say opposite, materials.

My parents met in London in the 60s. My dad was a turban-wearing Sikh born in India, and my mother was a Catholic girl, a bank manager’s daughter. They were both in medical school. Their world wasn’t ready for interracial love, and they faced resistance, sometimes even physical assault, just by going out in public. Their marriage resulted in my dad’s disownment, a lot of immigration paperwork, and a wandering lifestyle, first in Canada, then the United States. Eventually, they’d have three children, all in gradient shades of tan. They’d been trailblazers, even if no one recognised it, including them.

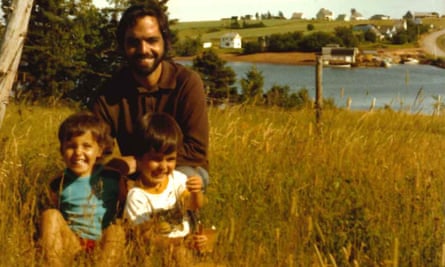

My father was no normal, western dad. He was quick-tempered as a younger man, thundering and strict. He kept his distance from nappy changes, the bedtime books, the drying of tears – these tasks fell to my mother, who had a full-time job of her own.

He didn’t play video games with my brother, nor let me paint his fingernails. He never wore T-shirts, shorts or trainers – not even on Sundays. He demanded exceptionalism from his brood, especially when it came to academic performance. Only we were second-gen kids, grass-stained and junk-food addicted, more interested in the hedonistic pleasures of our newfound home than doing our geometry homework. We failed him often.

He may have leaned hard on conservatism, but at the same time he embraced western extravagance with both arms. He loved flashy cars, fine dining and, just like his kids, TV and Coca-Cola.

I tiptoed around in my father’s shadow for much of my childhood, but this morphed into a furious teenage resentment. When I was in primary school I’d roamed all over the neighbourhood with my friends, free to go wherever I pleased. But once I hit puberty my father became intensely suspicious of my free-range habits. As a teen girl, I’d become a state of virginity in need of protection, encased in an awkwardly developing body. I became a stay-at-home daughter with not much distraction but soap operas, homework and our wall-mounted kitchen telephone whenever he was out of the house. The loss of autonomy outraged me – an emotion I’d inherited from him, naturally.

My parents split up when I was 16. A common enough story, except my British mum and South Asian dad had come from worlds apart, and conflicts in our household were waged over divergent traditions as much as irreconcilable differences.

In our household, it had never been easy to separate personality from culture. No conflict erupted without the influence of traditional values. No intergenerational strife, no marital discussion about gender divides existed in a vacuum. No bout of vexation unfolded without the social and economic pressures of the stratified world beyond our front door.

After the divorce, my mother gained custody, and my dad moved far enough away that we only saw him bi-annually. My siblings and I mourned the father we’d lost, and the one who might have been had he shared our mother’s foundations. Bbut I couldn’t talk to him without getting lost in a storm of blustery emotions. I blamed him for our calamities with the moral fury of youth, as-yet uncompromised by adult mistakes and letdowns. A silence filled the void, which entrenched over months, then years of inertia. But as I’d discover, there was no choosing sides without eliminating a whole culture along with it.

I went to university and began to write. I learned that stories, without empathy, lie flat on the page, bloodless and still. I devoured literature and history and began world travels of my own. I came to understand that our little family saga was just a tiny reflection of a much larger intercultural story. If the Raj hadn’t colonised India, nobody would have abandoned Punjab. My dad would never have arrived in London, never met my mother, and I wouldn’t exist, at least not as the living evidence of their remarkable union, which had been rare and even dangerous at the time.

In the post-divorce years, my lava began to cool, and a new curiosity moved in. I wondered what my father was doing, how he lived, what he did with his time. He was a hard-shelled, soft-centred extrovert, but was he all alone? A grudge was a lot like a suitcase. It took a lot of energy to carry. If I was going to haul it over many miles, shouldn’t I unpack its contents to see what was worth the weight?

There was a price to pay for cutting off connection. Without my father in my life, I’d lost my link to the Indian side of the clan, as weak as it had been to begin with in a half-white, immigrant nuclear unit, thousands of miles from the motherland. It’s hard to do culture without family. I struggled with my own biracial identity, stumbling to answer the question “What are you?” without resorting to pigeonholes: British or Indian, white or brown, two halves of a divided whole. I was as unreconciled within my half-brown body as our household had been on the eve of my parents’ separation.

It had always been a curry of emotion, allegiance and identity, everything cooked together, all at once.

After our wedding reunion, I began to visit my dad with tentative regularity, even though we still lived far apart. He’d never remarried but, despite his solitude, he’d rebuilt a mostly happy life. Soon enough, he became the kind of person who called me all the time just to chat, as if he’d been waiting for the chance.

We’d both changed as a result of our family break-up and the lonely years that ensued, which had softened us both, like a stonewashing for the spirit. He was still grumpy sometimes, but he’d also grown careful and appreciative. I was no longer the kid who’d feared him, who said I’d had enough of being his daughter. I was a grown woman with a husband and a household of my own. My willingness to make tea in my father’s kitchen, my presence by his side on the sofa, was entirely optional.

As a child, I’d seldom laughed in my dad’s company, but now he made quippy jokes, often delivered in conspiratorial murmurs. He remembered the houses we’d lived in, including the ones that I’d been too young to recall. He talked about his own childhood home with the avocado tree in the yard. He’d rarely mentioned his parents before, perhaps because the topic had been uncomfortable, marred as it was by his own intergenerational rupture. I’d never met my grandparents, but every detail about them felt like a missing link between two worlds – the one I’d been living in and a deep, ancestral dimension. In this way, my reconnection to my dad ended a chain of estrangement that had spread across three generations.

My father is now almost 90. I’m his chauffeur when I’m visiting, and I never know where we’ll end up when he hands me the keys to his old, red Mercedes. We visit his favourite hangouts, his friends’ houses, the cigar lounge, the steakhouse where we share meals off the same plate.

We arrived here by trial and error, testing the edges, which is probably no kind of prescription at all. But finding a way back gave me permission to exist in a mixed and messy middle, both racially and emotionally, allowing multiplicity and even doubt as a condition of its existence. From this in-between space of hesitation, I decided neither to forget nor to forgive but, instead, to loosen my grip on an old story that had never been just mine, all alone.

Almost Brown: A Memoir by Charlotte Gill is out now, published by Crown at £18