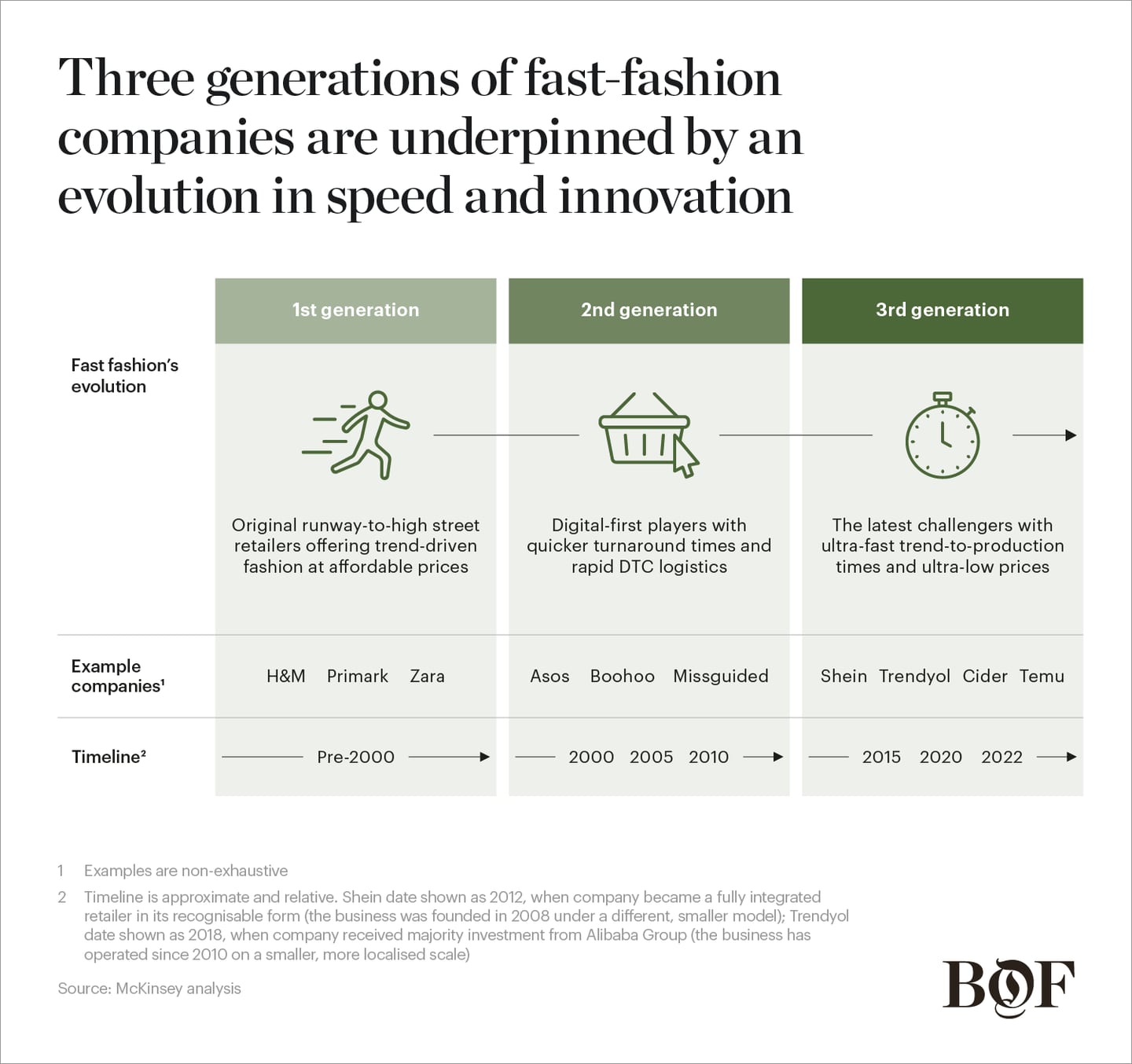

In 2023, fast fashion accelerated. Following in the footsteps of e-commerce giant and market leader Shein, a cohort of challengers has upended the competitive landscape by producing fashion quicker and cheaper than before. The first generation of fast-fashion heavyweights, like H&M and Zara, that introduced the concept of trendy runway-inspired fashion at affordable prices has before been challenged by a second generation of digital-first fast-fashion players like Asos and Boohoo. Now, a third generation of companies is making its mark. Rising players include Temu — a marketplace owned by China-based PDD Holdings, which overtook Amazon as the most-downloaded shopping app in the US and in most of the other 16 markets in which it operates just months after launching; Turkey-based Trendyol, a marketplace backed by Chinese internet giant Alibaba; and Cider, a US-based retailer targeting Gen-Z with a third-generation fast-fashion business model.

These companies, with their ultra-low prices and rapid turnover of trendy styles, have captured the attention of consumers in western markets. Two companies stand out in this regard: Shein and Temu (which are the focus of this analysis). According to the BoF-McKinsey State of Fashion 2024 Consumer Survey, 40 percent of US consumers have shopped at Shein or Temu in the past 12 months; in the UK, a newer market for the retailers, that figure is at 26 percent. Meanwhile, consumers indicate they are looking to increase their spend with these players: net future purchase intent for Shein and Temu is, on average, 18 percentage points higher than that of first-generation competitors.

Ultra-low prices are integral to the success of the business model. Shein’s average SKU price of $14 is significantly lower than H&M’s $26 and Zara’s $34. Turnaround times from trend capture to product availability are also condensed: Shein aims for 10 days, under half the 21-day minimum elsewhere. However, this speed does not always translate to delivery times — customers often wait weeks for parcels to arrive for the sake of trendy designs and low prices. Customer loyalty is built on more than just price or speed — the third generation of players is also transforming the customer experience through gamification, micro-incentives and social media communities.

Updating the Model

Undergirding the third generation are several operating model innovations:

Agile, scalable manufacturer-to-consumer supply chains: Some third-generation companies have developed large networks of suppliers who often manufacture exclusively for them. For Shein, which was initially built with a first-party, owned-inventory model (before introducing a third-party, cross-category marketplace in 2023), strict performance management of suppliers drives reliability, while direct-to-consumer delivery from China enables rapid scalability with low inventory risk. Temu, meanwhile, operates purely as a marketplace, finding manufacturers with excess capacity and onboarding them to sell unbranded goods directly to consumers in a low-price “B2B2C” model. While Temu’s prices are often between 10 percent and 40 percent lower than Shein’s, the retailer has faced challenges relating to quality control and reliability.

Data-driven product design and testing: At Shein, products are designed or selected using demand-driven trend modelling, which includes a range of data inputs from current trends to viral products to consumer perception. Shein adds between 2,000 and 10,000 items to its app every day and produces in small batches; to maintain a tight grip on inventories, hit rates comparing product page visits to sales are evaluated in real time. Temu’s approach also evaluates hit rates to feed back information to sellers on trends and demand levels for their products.

Loyal and growing customer bases: Third-generation retailers have focused on building large, deeply engaged, loyal communities. Shein’s multi-layered affiliate marketing influencer programme, paired with organic social community building, has driven viral user growth and low customer acquisition costs. Temu is investing in marketing in a bid to scale rapidly, posting more than double the number of Facebook ads in the US than Shein, and more than four times as many as Amazon. It reportedly spent $14 million for two 30-second slots during the 2023 Super Bowl, while market analysis suggests its quarterly marketing investments are nearly $500 million.

High app adoption rates and engagement tactics: Shein uses extensive in-app gamification, allowing customers to earn loyalty points by undertaking a variety of steps, including setting up an account, uploading reviews, watching livestreams and participating in outfit challenges. Temu similarly offers rewards to customers who invite friends to join and keeps users engaged with in-app games. Temu’s conversion rate is as high as 10 percent, compared with an industry average of 2 percent. Its retention rates rival those of Amazon, Shein and Walmart.

![Fast Fashion's Power Plays in Numbers Charts [1]](https://fashnfly.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/1702893198_322_The-Year-Ahead-Deconstructing-Fast-Fashions-Future.png)

Pushing Back

While they may have developed loyal customer bases, these third-generation fast-fashion companies are also subject to public and regulatory scrutiny. Consumers are increasingly aware of fast fashion’s role in the wider industry’s negative impact on the environment, while policy makers in key markets — notably the US and EU — are considering new laws to address the fast-fashion industry’s alleged role in a culture of overconsumption and make-take-waste.

Against this backdrop, some of the core tenets of the third-generation fast-fashion business model are becoming less attractive. The use of small-batch, reactive production has been positioned by some players as part of a “zero-waste” sustainability narrative. However, this type of production is also linked to rapid trend cycles, which go hand in hand with ultra-cheap products that are often quickly discarded. Some third-generation players have attempted, not always successfully, to promote a more sustainable, ethical side to their businesses through marketing campaigns. Shein’s recent influencer campaign to refashion the perception of its supply-chain ethics, in which a group of influencers were invited to a Shein innovation centre, was seen as an attempt to gloss over the company’s alleged association with unethical practices.

Many trade and tax bodies are considering new standards that address the way in which some third-generation fast-fashion companies have dealt with “de minimis” trade laws in jurisdictions like the US, where import taxes are less for shipping individual orders directly to customers from factories abroad, rather than in bulk — a common practice among third-generation fast-fashion players. US legislators are currently debating two bipartisan bills related to de minimis exceptions and customs and border scrutiny, which in their current form could mean that exporters from countries such as China (including major third-generation fast-fashion players) would no longer be eligible for de minimis exceptions and would instead face enhanced customs and border scrutiny.

The long-term prospects of the third-generation business model may face some challenges as players mature. For example, while Temu’s large performance marketing spend and discounts have so far helped the company to grow, it remains to be seen if it will be able to maintain its current strategy, which requires significant investments in customer acquisition and razor-sharp logistics.

![Fast Fashion's Power Plays in Numbers Charts [2]](https://fashnfly.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/1702893198_922_The-Year-Ahead-Deconstructing-Fast-Fashions-Future.png)

The Imperative to Adapt

The scene has been set for further disruption in the industry. In the face of incoming regulations, increasing public scrutiny and falling valuations (Shein’s $100 billion 2022 valuation reportedly dropped to $66 billion in 2023), third-generation players may not be able to settle into their business models just yet and may need to adapt again.

Shein is attempting to diversify its strategy in a bid to maintain its leading position. The company is experimenting with offline retail, including pop-ups and shops-in-shops. It has formed a joint venture with Forever 21 to expand its US offline experience, and has also recently acquired the Missguided brand in the UK. In response to import tax restrictions, Shein is also expanding its supply chain beyond its network of manufacturers in China, building warehouses in Europe, the US and Canada, as well as factories in Brazil.

As Shein adapts its model to face the new challenges — from a network of low-cost manufacturers largely in China to new suppliers elsewhere in the world, and from a direct-to-consumer online model to offline or omnichannel retail — what has been its competitive edge could face some dilution and the stickiness of its core customer base may be challenged.

The “everything store” marketplace model might hold the key to potential success for players. Shein has piloted the model in the US and Brazil and has indicated potential to expand in 2024. The retailer is even beginning to enter luxury fashion, with listings from some luxury brands posted by third-party sellers making their way onto its marketplace (although the authenticity of these items is, as yet, unverified).

In 2024, market disruption may gather pace, with third-generation fast-fashion companies doubling down on marketplaces to expand across categories, price points and consumer segments. Customer engagement is likely to remain a key differentiator, as third-generation players use their strong communities and gamification tactics to increase average basket size, seeking to grow profits and safeguard a viable business model for the future. The industry as a whole could feel the effects of these third-generation players: companies might want to take note of their most successful strategies to capture the attention of the modern consumer.

This article first appeared in The State of Fashion 2024, an in-depth report on the global fashion industry, co-published by BoF and McKinsey & Company.