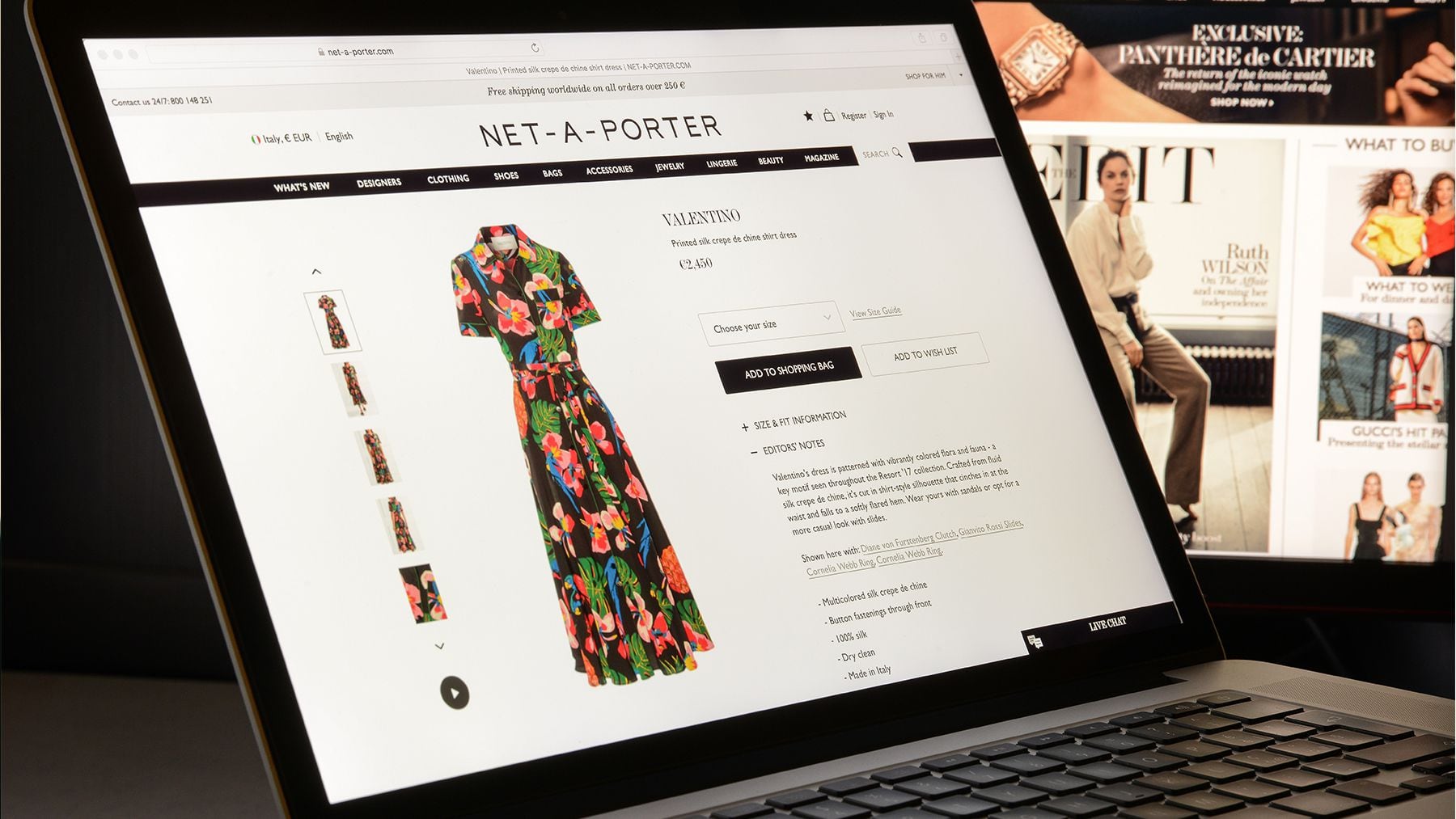

Luxury and e-commerce have always had a complicated relationship.

When Natalie Massenet launched Net-a-Porter in 2000, most luxury brands still viewed online shopping with some distrust. It wasn’t clear how a small, digital image could convey what was valuable and worth splurging on about high-end fashion’s high-touch products. Technology, in this case, seemed to be adding a barrier between product and consumer, not removing it.

But even if brands weren’t ready to open e-commerce themselves, enough were willing to give Massenet’s idea a shot to make Net-a-Porter the first big shopping destination for luxury online. Massenet proved right, of course: Consumers were willing to buy luxury online.

Eventually the brands came around, and they became their retailers’ biggest competition, contributing to the serious challenges those retailers are facing today. In the US, for instance, consumer spending at online luxury sellers suffered a sustained decline through 2023, according to data compiled by Earnest Analytics for BoF, with Earnest tracking double-digit drops in 11 of 12 months. Net-a-Porter as well as Farfetch and Matches are among the retailers included in the category.

The struggles aren’t brand new. Multi-brand luxury sellers have been under pressure for some time. But conditions only seem to be getting worse.

The question is whether the model itself is broken — in part because brands that once shied from selling online have now fully embraced it.

Last year was a particularly harsh one for luxury e-commerce players. Farfetch was in danger of collapse until its last-minute acquisition by Coupang, a South Korean e-commerce giant that provided $500 million in emergency funding. Frasers Group scooped up Matches in a deal that left its previous owner, the private equity firm Apax Partners, with heavy losses. Sales at Yoox Net-a-Porter dropped 10 percent in the six months from April to September, Richemont said. And while privately held Ssense doesn’t report its financials, it started 2023 with layoffs, suggesting struggles of its own.

But not all online luxury suffered equally. Total luxury e-commerce actually grew, according to data from Coresight Research — and grew slightly faster than the overall luxury market, which had a slowdown in 2023. Coresight expects that growth to continue in the years ahead, while a separate report released in January by the consultancy Bain & Company forecast online luxury sales would rise from about 20 percent of the market today to account for as much as 33 percent of sales by 2030. Shoppers keep buying fashion online, including high-end items.

More often, however, they’re doing so through a brand’s own e-commerce channels rather than through multi-brand retailers, said Sunny Zheng, senior analyst at Coresight. There are a variety of reasons, such as assortment: Brands frequently keep their best sellers exclusive to their own channels, leaving third-party retailers with what’s left. You’ll never see a Louis Vuitton Neverfull handbag listed for sale on Farfetch, unless it’s a secondhand item, she noted. But there are other factors too.

“[Comparing] the experiences, the authentication and also the brand trust … there’s no attraction for consumers to go to Farfetch and Ssense,” Zheng said.

Luxury E-Commerce’s Challenges

The issues for multi-brand online luxury sellers aren’t simple ones to fix. In a November note to clients, analysts at Bernstein examined the “consumer of the future” and the impact on different industries. Fashion aggregators — i.e. large multi-brand retailers — face a number of challenges: Consumers build emotional connections foremost with brands, giving brands most of the power; consumers are already overwhelmed by choice, a problem aggregators only add to; and as far as the shopping journey goes, consumers now look to social media for the inspiration and product discovery aggregators once offered.

The more successful luxury e-commerce sellers such as Mytheresa manage to differentiate themselves through offerings like exclusive products and experiences that keep high-spending clients coming back. The company’s sales grew 12 percent in the quarter ended September 30, including a 29 percent jump in the US, despite the tough environment, though the usually profitable business did record a loss in the period.

Others may end up competing on price. Ssense has developed a reputation for widespread markdowns, as documented by the fashion newsletter Blackbird Spyplane in a story examining the effect on the fashion ecosystem. Zheng pointed out that Farfetch became popular a decade ago because it offered a number of discounted items and sold globally.

At the same time, these businesses can have high operating costs from maintaining their logistics and technology platforms, while the price of acquiring customers on social media has surged over the years. It only makes it harder for them to grow and turn a profit.

In Zheng’s view, the business model isn’t going to die, though. Wholesale still matters to brands, small ones especially but big ones too, and being a multi-brand online luxury retailer can still work. But those businesses need to have a great product assortment and work closely with brands on pricing strategies.

Without rethinking their approach, many luxury e-commerce companies will find themselves diminishing in importance as brands increase their own direct-to-consumer sales. In its report, Bernstein surmised that consumers will keep using fashion aggregators, but mostly to get access to smaller brands and for shopping in smaller markets.

“Without compelling personalisation or a differentiated customer proposition, aggregators will end up being low-margin distribution businesses, running the risk of facing consumer irrelevance and ending up like department stores — dead,” the analysts wrote.