PARIS, France — In one of those hyperbolic moments that delighted all who knew her, Diana Vreeland once claimed that Chanel “invented the twentieth century for women.” The statement has a stirring ring but it is not true. It was Paul Poiret who created clothes that pointed to the future: a future all couturiers, including Chanel, tapped into in the twenties and thirties, a time when, ironically, Poiret, the great inventor and beacon of modernity, was out in the cold. Never able to reinvent himself, he remained there until his death as a neglected and forgotten pauper.

Like Charles Worth, for whom he briefly worked, Poiret was a turn-of-the-century archetype of the grand couturier as dictator, a job both men seemed to enjoy as much as, if not more, than dressing women. Together, they set the tone for the role of the “great designer” still with us today. The tantrums, the refusal to accept legitimate criticism, the need for adulation: these and many other characteristics of the great designer sprang from the attitudes of these two extraordinary men who could understand and interpret the moods and needs of the women of their time more fully than most present day designers do, because they worked on a small scale where every client was known — and so were her dress attitudes and lifestyle.

Paul Poiret, once described by Jean Cocteau as looking “like a huge chestnut,” had the figure and mental attitude of a worker but his personality was more complex. He was heterosexual and he moved in the social circles of the women he dressed, including his wife, whom he used as a model. She attended grand social occasions in Poiret’s most striking creations with the intention of attracting the attention of fellow guests who would, in considerable numbers, beat a path to her husband’s maison de couture, determined to be a member of the coterie of smart women dressed by him, regardless of his very high prices.

The fashionable world of Paris in the early years of the twentieth century, when Poiret’s powers reached their zenith, is not easy for modern minds to understand. Inside the closed, upper class society of pre-World War I Paris, breeding and “class” are what opened the gilded doors of high society, along with a certain social notoriety.

Actresses, dancers and even music hall performers, if they were in a liaison with a man rich and powerful enough to silence all but whispered criticism, were admitted by many couturiers, albeit on sufferance. Paul Poiret, with his eye for publicity, welcomed them — even the courtesans.

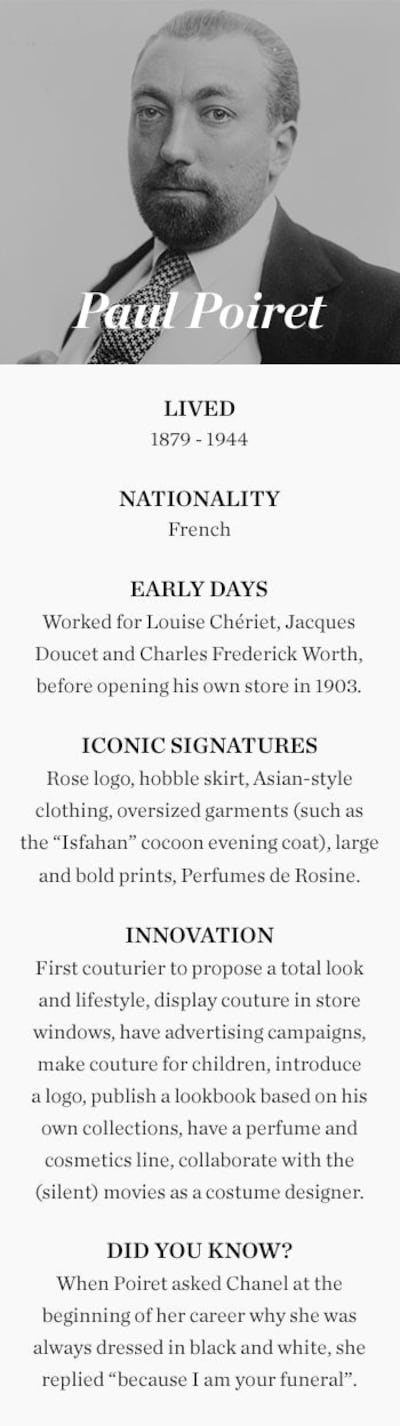

This world of display became Poiret’s playground, although it was not one into which he was born. His father owned a small textile business and the family was comfortably bourgeois. Born in 1879, a true Parisian, there was little in Poiret’s early years that might suggest the glittering career to come — a career not without its problems, largely caused by the personality and ego of the man himself. But not entirely.

Poiret was caught at one of the intersections of history where the signposts are not very helpful. His was a time when European culture was dominated by three geniuses: Poiret himself, Sergei Diaghilev and Marcel Duchamp. Add the Wiener Werkstatte and that was the cultural mix of the day, which moved not only fine art, but also design and applied art to a point where they could make the European statements that created the culture of the twenties for the rest of the world.

And Poiret was very much part of this, though briefly. He was barely a player in the post-war scene, a legend for all the wrong reasons — his extravagance, arrogance and irresponsibility, rather than for his contribution to fashion and style.

So what were the achievements of this unique man? Well, with hindsight, we can see that his feet were firmly placed on the road signposted “Modern” and he knew how to walk along it with as much assurance as Chanel, Vionnet or any other couturiers in Paris. But unfortunately, in his early days his magnificence and splendour were so overwhelming that anything after that was seen as a diminution or even a disappointment. The concept of the creative light, so bright and strong that it cannot be adapted or changed, is a very real one in fashion, as in art forms. Both Diaghilev and his Ballets Russes and Poiret with his “barbaric” clothes and fabrics were trapped in a “One Thousand and One Nights” bubble from which they could not escape. Janet Flanner, the New Yorker’s famed Paris correspondent, hit the nail on the head when she referred to “genre Poiret” — in other words, something fixed and unchangeable.

But Poiret’s legacy was not just the magnificence of his clothes. He was also a trader who had ideas well before his time. His lack of business skills meant that, instead of being the millionaire he pretended to be whenever he had some money, he died a pauper’s death. He was a born optimist and, of course, an arrogant, self-indulgent man. When his fortunes were very low his friends collected 40,000 French francs to help him. Poiret reputedly spent it on a telescope, a refrigerator and a lot of premier Cru Champagne. Such self-indulgence meant that during World War II Paul Poiret was reduced, at one time at least, to making himself a suit from a beach peignoir and begging strangers to pay for food and drink in cafes. He died in 1944. One commentator pointed out: “No couturier ever had so many enemies at the same time as so many fanatical supporters”.

But why did women beg him to dress them even though they knew that his radical cuts and colours meant they had to throw away clothes from other couture houses, because Poiret’s approach was so advanced and radical that they didn’t work with any other designer’s garments. They fell in love with his Arabian Nights colours: the tassels, the volume, shape and looseness of his cut, the osprey feathers, the ropes of pearls, the “barbaric'” jewellery, the eclectic mix of kimonos, the Batik, the Persian influences — all of which were central to his creative mélange, even though he evolved many of them long before he had even travelled beyond the shores of France and seen other cultures first hand. He claimed that he liberated women by abolishing the corset (a claim contested by supporters of Vionnet and the dancer, Isadora Duncan), and he certainly introduced the hobble and lampshade skirts that had great influence in their time.

Poiret was early 20th century fashion’s magician and intellectual. He read books, visited galleries and met many of the great artists in Paris in the 1900s. He was instinctively aware in the way that Vivienne Westwood is aware. And, like her, he was bold — even reckless. When Diaghilev brought his famous Ballets Russes to Paris in 1909, it caused a sensation. Its music, choreography and, above all, sets and costumes, changed French culture almost overnight. Its effect on fashion was muted. Worth and Doucet, both of whom Poiret had worked with at the beginning of his career (he once said that it was at Doucet that he learned ‘everything’), knew their customers and the rigid dress codes of Parisian high society well enough to “not frighten the horses” by dramatic change. But Poiret was ready for it. In fact, he claimed his experiments in colours and patterns, so similar in many respects to the Ballets Russes, and for which he became famed, actually pre-dated the ballet company’s arrival in Paris. An arguable claim to say the least.

But if there is no proof of “who got there first”, there are certain undisputed firsts in Poiret’s career to support the claim that he was as revolutionary and as far-thinking in his field as Duchamp was in art. Having opened his own maison du couture in 1903, he already had ideas that he knew that the very traditional house of Doucet would never have countenanced. He was the first couturier in the world to introduce his own fragrance and in 1911 set up his own costume and fragrance company, which he named after the eldest of his five children, his daughter, Rosine.

Another first was to broaden high fashion to include interior decorating and fabric design with a company called Martine, named after his second daughter. By training young women as designers and craftpersons, Poiret put himself in line with the experiments and theories of the Arts and Crafts movement pioneered by William Morris. Other firsts included selling copies of his couture garments described on the label as, rather hubristically, “Genuine Reproductions!”

In 1914, he introduced the designer tour, which led to the trunk show (still part of many selling stratagems in designer fashion today), when, with nine models, he set out to bring his fashion to Central Europe, where he was hailed as a hero. He was fearless in his beliefs and totally confident in his abilities. And he spent the money to show it. In 1911, his Thousand and Two Nights party was a magnificent homage to Orientalism. The next year, his party theme was Les Fêtes de Bacchus. Both cost a small fortune as in those days, unlike now, fashion parties were a personal rather than a corporate enterprise under-written by cosmetic and beauty companies. He gambled recklessly in his last party, in 1925, which took place on three decorative barges moored on the Seine. His already perilous finances never really recovered.

So, in Paul Poiret we are looking at a classic example — almost the archetype — of the couturier, extravagant and untrammelled. But in the same genre is the blindness that sees just one road, for better or worse. Charles James, Cristôbal Balenciaga, Vivienne Westwood, John Galliano, Alexander McQueen and Yohji Yamamoto; all followed their own dream and most would find an answering cord in Poiret’s obiter dicta such as, “You will not learn to be beautiful from fashion magazines; what have they to do with fashion?”