Fashion is embracing a new dimension.

Brands can now quickly and routinely create ultra-detailed 3D captures of their products to use for design tasks, in their marketing, on their e-commerce sites and in augmented-reality experiences such as virtual try-on, with more applications still emerging. Not so long ago, that required large photogrammetry rigs mounted with an array of cameras and lights that let you photograph an object from all angles. Today, they can produce these 3D twins with as little as an iPhone, a lighted box to serve as a mini studio, a laptop and software from providers like Adobe.

“What makes this exciting is that basically you can create the 3D asset once and derive any kind of content from it,” said Franz Tschimben, co-founder and chief executive of Covision Media, which builds more powerful 3D scanners used by brands such as Zara and Adidas.

The need for 3D imagery is growing as fashion expands into more virtual spaces. For brands to put versions of their products in video games or create immersive content for mixed-reality headsets like Apple VisionPro can require 3D models that developers can use. Last year, LVMH announced an expansion of its partnership with Epic Games, maker of the game Fortnite, as part of an effort to create virtual experiences for its brands and digital twins of its goods.

Shoppers may already see parts of these 3D models on a regular basis. While old-fashioned product photography still rules in fashion, some 2D shots consumers encounter online can be taken from 3D captures. Covision said its work appears on Adidas’ e-commerce site as product shots for shoes such as the brand’s Terrex Free Hiker 2.0.

“It is definitely the thing we see driving a lot of the 3D usage,” said Michael Tchao, who is on Apple’s ProWorkflow team, which tests and refines the company’s products according to the needs of customers and developers.

He called it “the secret big deal of 3D.”

Apple and Adobe highlighted that use and others at an event in New York last week to showcase their 3D technologies to the fashion industry. As part of the presentation, members of Coach’s 3D team demonstrated how they make 3D assets of products like the brand’s successful Tabby Bag by taking a number of smartphone pictures — ideally at least 70, but fewer can work — of the item inside a lighted box, dropping the shots on a laptop and using software that assembles them into a 3D image.

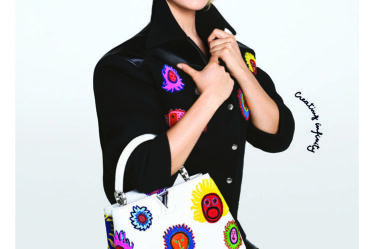

The brand uses them to create detailed mockups of its products — something it couldn’t do just from photos or videos. It can similarly snap a picture of a material swatch, import it into the software’s library, adjust characteristics like sizing to make sure details like leather grain are correctly proportioned and then drop it onto the 3D object. It has also turned them into marketing assets. In keeping with marketing’s trend towards surrealism, it has used 3D models in social media posts like one by a digital artist who depicted a the bag floating through a subway station.

Creating such a detailed 3D capture might have once taken hours or days, Coach said, but now it can do it in about 30 minutes, yielding a model that’s accurate down to the scratches on the hardware. That change is due to advances in technology.

A few years ago, for example, Apple — which Tchao acknowledged wasn’t always the first choice for designers working in 3D — saw broad applications for 3D captures and started building object-capture APIs into its operating systems and adding support for 3D files. It also optimised its systems to make the process of creating 3D models faster and simpler, according to Doug Brooks, a product manager on the Mac team.

While moves such as these helped eliminate the need for specialised equipment, software reduced the need for specialised skill sets. Fashion companies typically had separate roles for working with photogrammetry, using 3D tools and managing and digitising material samples, said Pierre Maheut, who heads up the partnerships team for Adobe’s immersive and 3D tools. Today, one person can handle all those tasks.

Of course, depending on the quality of the capture, it can still be evident you’re looking at a 3D model rather than a photo or video. The Tabby in Coach’s surreal Instagram post still has a digitised feel. But other companies are working to make their models look as real as a regular.

Covision Media’s scanners take some 15,000 pictures that they crunch into a 3D model in a few hours with little post-production finishing required. It’s more like classic photogrammetry, but Tschimben said the company has a unique method of measuring the reflection of light off an object and is faster than other techniques at producing detailed models. He compared it to mass production of 3D.

It now has two different scanners — a first-generation model suited to rigid items like shoes and a newer one for flexible objects such as clothes and bags — that it sells or rents to companies. Tschimben said businesses might keep one of the scanners, which stand about 6.5 feet wide and as tall as 8 feet or so, in their offices but could also put them at factories so they can see accurate models of samples without having to ship the physical product back and forth.

In addition to the current uses of 3D assets, Tschimben sees another big one on the horizon. The ongoing development of text-to-3D generative AI models, similar to those that exist for producing 2D imagery, means brands may one day soon be able to design products in 3D using AI. But for a brand to infuse its stylistic DNA into the output, it needs its own high-quality 3D datasets to train the model on. It’s another reason for companies to capture their products in 3D.

“To do this at scale for a company — let’s say for Adidas — in the future, we could go into this, since they are building up a huge data set,” Tschimben said. “[3D] datasets specifically tailored to their products and their company, they hold a lot of value.”