The dealings of Asia’s second-richest man demonstrate how investors’ motivations can be far more complex and multi-faceted than they seem. Reliance Industries Limited chairman Mukesh Ambani spent nearly $1 billion in the first quarter of this year on companies in e-commerce, energy and other sectors, but it is the Indian magnate’s much smaller investments in fashion that have attracted a disproportionate amount of attention.

Through its retail arm, the conglomerate has longstanding partnerships with many international luxury brands, including Bottega Veneta, Burberry, Canali and Jimmy Choo, for the India market. More recently, it started buying up stakes in Indian designer brands, triggering a frenzy of M&A activity as the ambitions of Ambani collided with those of billionaire rival Kumar Birla, chairman of Aditya Birla Group.

According to Darshan Mehta, chief executive of Reliance Brands Limited (RBL), the Reliance Industries Limited subsidiary that has been most active in these deals, Ambani’s motivations are straightforward, despite claims made by observers to the contrary.

“[Our] focus has and continues to be on the top 10 million customers in India. This is true whether the brand is of Indian or international origin,” Mehta said. “A Bottega or Versace consumer more often than not also wears a Rahul Mishra dress or an Anamika Khanna lehenga or even Sabyasachi jewellery.”

Upmarket Indian designers — particularly high-profile players active in the bridal wear segment boasting celebrity clients — are an obvious way for investors to increase their exposure in the Indian luxury goods market, which Euromonitor International estimated to be worth $2.6 billion in 2021. But even with projected growth of 12 percent annually through 2026, the market will remain relatively small compared to other business opportunities in India and other luxury markets across Asia.

While some Indian designer brands clearly represent an attractive long-term play for local investors, the category may not be the most lucrative in the short-term. So there must be something else motivating these conglomerates beside the price positioning of the brands they are targeting.

Not a Case of Building India’s LVMH and Kering

For four years, Reliance Industries Limited and Aditya Birla Group have been locked in battle over some of the country’s most well-known designer brands.

Companies owned or controlled by Reliance, including RBL, have invested in Rahul Mishra, Anamika Khanna, Raghavendra Rathore, Manish Malhotra, Abraham and Thakore, Abu Jani and Sandeep Khosla and Ritu Kumar. Meanwhile, Aditya Birla Fashion and Retail Limited (ABFRL), a subsidiary of Aditya Birla, have invested in Sabyasachi, Shantanu and Nikhil, Tarun Tahiliani, the House of Masaba and traditional Indian fashion retailer Jaypore.

Throughout the buying spree, media reports have drawn parallels between the two Indian groups on the one hand, and European players LVMH and Kering on the other, framing it as a way for the former to become local counterparts of the latter. But market observers have poured cold water on that argument.

“The comparison… is like apples and oranges. LVMH, Richemont and Kering are multi-brand conglomerates within the personal luxury goods industry. [They] can in no way be compared to these businesses in India due to the [latter’s] completely unrelated diversification [across sectors outside the luxury industry],” said Ashok Som, professor of global strategy and founder of the India Research Centre at ESSEC Business School.

Seeing the Indian groups’ designer investments as part of a strategy to move up the fashion value chain only goes so far.

Though Reliance Industries can trace its roots back to the yarn trade, it has evolved from a polyester fibre producer to an oil and gas giant with interests in everything from financial services to digital infrastructure. Likewise, Aditya Birla’s textile industry heritage — which centres around the production of viscose — is often overshadowed by its holdings in unrelated sectors, such as telecoms, cement and aluminium.

Why then are multi-category, mass market giants like Reliance, India’s largest listed company with gross annual revenues surpassing the $100-billion mark, and Aditya Birla, which counts over 100 nationalities among its 140,000 global employees, bringing a bunch of relatively small, niche designer fashion businesses into their sprawling portfolios?

One Indian fashion industry insider who spoke on the condition of anonymity suggested that many of the investments had been in the pipeline for years, and that the financial pressures designers faced during the pandemic simply accelerated the completion of the deals in one big wave.

Behind closed doors, sceptical pundits have characterised some of the investments as attempts by the conglomerates to snap up small, gilded trophy assets; to fulfil the vanity projects of family members and key executives; or to provide a training ground for succession planning.

Others point to the potential marketing value of the investments. Though some of the designers targeted certainly do have sufficient brand equity to help inject some glamour or cool factor into the groups’ reputations, others are less valuable as a brand association.

All the designers do, however, have something in common which could help explain the groups’ rationale for recent deals. Even though most also borrow from the Western fashion palette, they all authentically tap into the diverse silhouettes, embellishments and other elements of traditional Indian clothing. That is a valuable proposition in India which most international luxury brand competitors can’t leverage.

For Reliance, acquiring Indian designer brands therefore serves to complement the group’s stable of international brand partnerships. For Aditya Birla, whose portfolio is dominated by non-luxury Indian brands such as Pantaloons and includes partnerships with only a few international labels such as Ralph Lauren, Ted Baker and Fred Perry, the acquisitions appear to be part of a strategy to move upmarket.

Both groups will have experienced first-hand the difficulty of translating certain international brands for the Indian market. Indeed, many foreign players have gone through a tumultuous time in the country over the past twenty years. As a result, the bet being made now on domestic fashion brands is — to some extent — a hedge by the conglomerates against the often more challenging international designer segment in India.

The Traditional Indian Clothing Opportunity

The traditional clothing and accessories market in India is valued at approximately $21.2 billion according to a 2020 estimate by Technopak Advisors. As little as 12 percent of that is in the organised sector. Unbranded traditional fashion still dominates luxury consumption across India and, like in the mass-market, it is often sold through informal retail channels.

This leaves an overwhelming proportion of the market open for companies to organise and professionalise as the Indian fashion market evolves in the years ahead. What motivates players to do this, among other things, is the higher profit margins that often come with formalisation.

Anker Bisen, senior vice president of Technopak’s retail and consumer products division, tends to see the recent raft of M&A activity through this prism. He also cites the potential for buyers to grow comparatively small businesses with outsized name recognition operating in a highly segmented category.

“Premium [traditional Indian clothing] is a close proxy to occasion wear [for weddings, festivals, special events etc.] There are opportunities for many of these labels who are widely known and are trendsetters but lack scale,” said Bisen.

In the mass market, the robust performance of traditional fashion is reflected in the upcoming IPO of Fabindia, which analysts expect to reach a valuation of $2 billion. Founded in 1960 as an exporter of Indian textile crafts, the company has grown from just one store in 1976 to more than 320 across India.

“Fabindia is now a broad-based retailer [including] home[ware], furnishings, cafés [etcetera] rather than just selling traditional clothing. Loosely, it is [in India] what Marks & Spencer is in the UK,” Bisen said.

Though it occupies a lower value segment than most recent designer acquisition targets, Fabindia nonetheless points to how multi-category brand empires can be built from the Indian consumer’s appetite for branded traditional clothing sold in a formal retail environment. The challenge for Reliance and Aditya Birla will be to do something similar in the premium to luxury market.

The conglomerates clearly have this in mind as plans have been announced to expand brands’ footprint by hundreds of stores and product extensions in categories such as homewares.

“The acquisitions by the likes of Reliance… and ABFRL provide an opportunity for these labels to grow bigger both in India and overseas,” Bisen added.

To do this, the groups will have to manage scaling-up production and international operations for customers in the South Asian diaspora and beyond, without succumbing to brand dilution.

Demi-Couture Brands Launching More Affordable Lines

It is still too early to assess the return on most of these investments, not least because of the disruptions caused by the pandemic. However, some of the stated ambitions are bold — particularly for designers of traditional Indian fashion operating in booming sectors like demi-couture and bridalwear and those in the underserved men’s luxury segment who want to scale their businesses by serving the mass market.

Take Aditya Birla’s aims to grow Tarun Tahiliani into a $69 million business over the next five years, by opening more than 250 stores across India. Having invested around $9.25 million in February 2021 for a 33 percent stake in the main luxury business, the group’s subsidiary ABFRL has since overseen the launch of a more affordably priced traditional menswear label by the designer called Tasva in which it holds an 80 percent stake. Whereas an elaborate womenswear kurta in Tahiliani’s main line can sell for $620-2500, a Tasva kurta costs around $25-125.

Similarly, after Reliance teamed up with the Ermenegildo Zegna Group to pick up a minority stake in Raghavendra Rathore, it helped the designer launch a more affordable line called RR Blue, which has kurtas priced at around $125-150.

In the case of Anamika Khanna, the 60 percent Reliance stake is in her second label AK-OK, with the group suggesting it does not intend to get involved in the designer’s more expensive namesake label. The growth strategy for this deal and most recent investments appears to be focused on the domestic market but, in a few cases, the investors have explicitly pointed to ambitions abroad.

Reliance may yet launch new verticals for Manish Malhotra, for example, but the group seems to be betting its 40 percent stake on the success of the designer’s main line through international expansion

Malhotra’s existing clients among the Indian diaspora in Europe, the US and the Middle East, “are bankers, tech people, aspirational and wealthy [so]… it’s a good starting point,” Mehta told BoF, at the time of the investment.

“I’m more confident than ever that the next Giorgio Armani or Valentino on the global stage will come out of India and we want to be there as a partner [when it does],” he added.

To see how realistic this ambition is, many will be watching the evolution of Sabyasachi Mukherjee. Reliance’s rival Aditya Birla acquired a 51 percent stake in the designer’s successful namesake brand Sabyasachi last year through ABFRL.

Beyond the India market, the Kolkata-based designer has already established links with foreign retailers like Bergdorf Goodman and launched several high-profile international collaborations including those with Christian Louboutin and H&M.

However, investing in the likes of Sabyasachi or Bollywood favourite Malhotra, who has four stores in Delhi and Mumbai, is a very different proposition to the acquisition Reliance made last year in the business of craft pioneer Ritu Kumar, a company with a nationwide footprint of 64 stores, including several thriving diffusion labels.

According to Amrish Kumar, son of Ritu Kumar and chief executive of her business, the investment will enable the “growth of stores and online product extensions in existing categories and new ones [as well as a] clearer demarcation of business models for each of the brands.”

“The most obvious change will be our spread of distribution. We expect to double our store count in 18 months, mostly for [the more affordable] Aarke and Label brands [rather than the namesake label]. We’ll also be more visible across online platforms and departmental stores,” he added.

Projecting a Positive Image of India and Indian Business

The degree to which conventional business logic motivates recent M&A activity in the sector varies from one deal to the next, but some can be better understood when seen through the lens of impact investment.

Though impact investment is usually focused on positive outcomes for the environment and workers’ rights, a more liberal interpretation of ESG principles includes the protection of tangible and intangible cultural heritage — something which many Indian designers are seen to guard.

Fashion has long been a tool to win hearts and minds in India, where it is so intimately linked to craft’s emotive power to invoke national pride and a sense of moral high-ground through the Gandhian legacy of Swadeshi (loosely translated as self-sufficiency through Indian-made products). The legacy is not lost on Reliance, which is now launching a new brand called just that, Swadesh, which will work with artisans across India.

Insofar as the preservation of nationally or internationally important applied arts — a field which includes fashion craft — is considered part of the collective social good, some investors will spend their money on assets that relate to that field, even if the deal isn’t explicitly earmarked as an ESG investment.

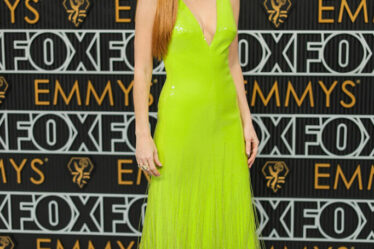

For instance, when Reliance invested in Rahul Mishra earlier this year, Isha Ambani, daughter of the group’s chairman and director of Reliance Retail Ventures Ltd (the holding company of all Reliance Industries’ retail assets), framed the deal as “a strategic part of our ongoing commitment to nurture Indian art and culture.” In particular, she noted Mishra’s ability to “[spotlight] Indian expertise in crafts globally,” a reference to his participation in Paris couture week.

Mehta explained the rationale to BoF in more holistic and conventional terms, with his goal being to launch a ready-to-wear brand focused on international growth for Mishra spanning beauty, jewellery and homewares. “Very often people get into partnerships because they want to tick a box, or to put it crudely, pick up a trophy, but we have spent a lot of time thinking about mutual respect and what we both bring to the table,” he said.

The different ways the Reliance leaders described the acquisition is interesting because, though Mehta no doubt expects his expansion plan to achieve a clear return on investment measured by bottom line performance, Isha Ambani seems more motivated by the use of home-grown luxury brands as cultural assets to help boost Reliance’s soft power on a bigger stage.

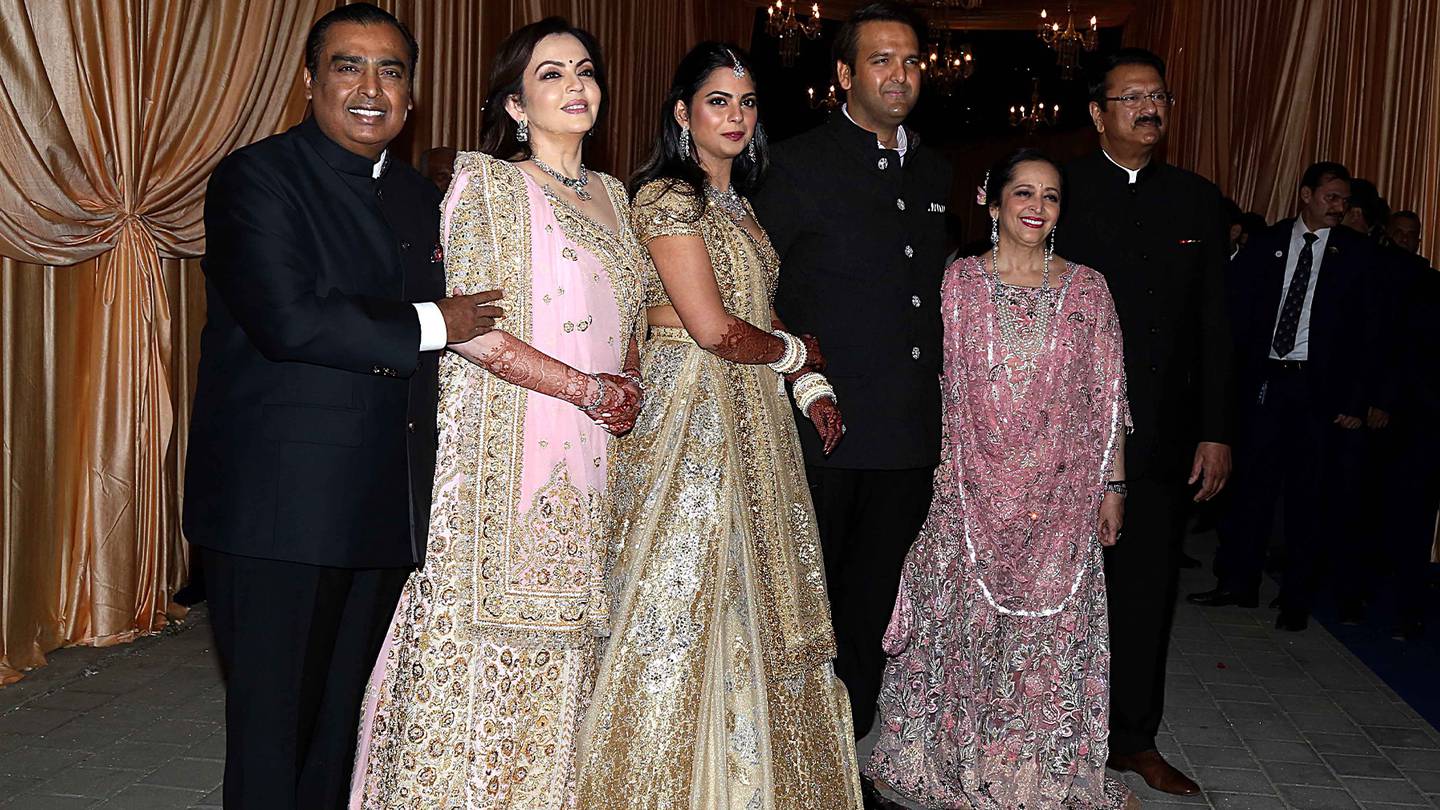

The Ambani family’s framing of fashion as an applied art conveniently fits with other roles they occupy in the creative industries. Nita Ambani, wife of chairman Mukesh and chairperson for the non-profit Reliance Foundation, was elected to the board of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in the US in 2019 and daughter Isha Ambani was appointed to the board of trustees of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art in 2021.

The cultural dimension doesn’t end there for Reliance. An integral part of the group’s Jio World Plaza, a luxury mall the size of 10 football fields scheduled to open in Mumbai in 2023 in which Isha has been closely involved, is a cultural complex called The Art House, headed by Nita. The mall will see global luxury brand boutiques erected next to those of the Indian designers backed by the Ambanis; the art house will showcase the works of both Indian and international contemporary artists.

These tactics aim to project a positive, modern image of both Reliance and of India to the rest of the world which, in turn, company leaders hope will help to persuade international businesses of Reliance’s credentials as a good prospective partner — or buyer. In 2019, Reliance acquired upmarket UK toy store Hamleys and media reports suggest the group is now gearing up to make a joint bid for British pharmacy chain Boots, an important distribution channel for global beauty brands, and a bid for Revlon in the US.

There is also a more cynical narrative worth considering when looking at Reliance’s motivations. Company executives may be hoping that the right fashion brands, seen through the prism of their artistic and craft heritage, can help sanitise the image of a corporate giant that profits from so-called “dirty industries” like oil, gas and coal mining. This may still be possible in India, despite the fashion industry’s own highly problematic environmental and social business practices.

At Reliance’s competitor Aditya Birla, recent investments in Indian designer brands also appear to have also been used to bolster the conglomerate’s image, albeit in more tangible ways such as attracting finance. The firm’s investment strategy was given a nod of approval by at least one influential global player in May when Singapore’s sovereign wealth fund GIC approved an injection of 2,195 crore rupees ($282.8 million) for 7.5 percent of Aditya Birla’s fashion and retail subsidiary ABFRL.

Ashish Dikshit, managing director of ABFRL, said that GIC’s capital infusion will allow ABFRL “to accelerate… growth [and]… fortify our position as one of the leading players in the industry.”

Having snapped up a dozen Indian designer brands between them over the last four years, Reliance Industries Limited and Aditya Birla Group are motivated by a unique combination of factors, some more straightforward than others. And though the contest between them and their respective leaders has been both dramatised and, at times, misunderstood by the media, the competitive aspect of their relationship cannot be ignored.

Among India’s leading industrialists, fierce battles are regularly waged over everything from commodities to telecoms. Fashion, with all its cultural significance, relationship to soft power and undeniable sheen of glamour, may not be the most financially lucrative sector in their sights. But it may prove to be key to gaining an edge in what many now describe as India’s “new gilded age”