The fashion industry operates on an outdated manufacturing system that is ripe for disruption. With many practices remaining unchanged for more than 50 years, fashion’s supply chains are neither responsive nor sustainable enough. With brands hunting for the lowest prices, manufacturing practices have become fragmented as brands outsource more and more of their production to sprawling networks of suppliers in developing countries. The number of factories has mushroomed, along with unauthorised subcontracting.

At the same time, logistics gridlocks and macroeconomic pressures continue to weigh on global supply. The war in Ukraine forced the re-routing of trade and triggered an energy crisis, while ageing port systems across the globe are creating transport bottlenecks. Global inflation has pushed up input costs — cotton and cashmere prices have increased 45 percent and 30 percent year on year in 2021 respectively — and extreme weather is hitting developing economies like Pakistan where, alongside the tragic loss of human life, as much as 45 percent of the country’s cotton crops were wiped out by floods in August 2022. As such, more than half of fashion executives in the BoF-McKinsey State of Fashion 2023 Survey identified supply chain disruptions as one of the top risks hampering the growth of the global economy in 2023.

Meanwhile, the softening of consumer demand is causing many brands to reduce their order volumes, squeezing manufacturers’ revenues. In a 2021 McKinsey survey of apparel chief purchasing officers, 66 percent said they anticipated increased volatility in consumer demand. If these and other pressures continue, margins across apparel manufacturing are expected to shrink 10 percentage points by 2030.

Amid the diverse sources of pressure on fashion’s supply chains, the system is beginning to show signs of change. To future-proof their organisations, manufacturers are adapting to the needs of fashion brands seeking increased flexibility and shorter lead times so that they can accommodate swift changes in consumer demand and unpredictable logistical disruptions. Enabled by enhanced digitisation, they will lean into new supply chain models based around vertical integration, nearshoring and on-demand systems.

From Suppliers to Partners

To mitigate risks and increase control along supply chains, some manufacturers are joining forces with producers from different specialities. For example, US textile manufacturer Mount Vernon Mills acquired a yarn spinning and weaving facility from Wade Manufacturing Company, also US-based, in a bid to gain more flexibility over its production. In Asia, Sri Lanka-based manufacturer MAS Holdings in August 2022 acquired the assets of Bam Knitting, one of the country’s fabric producing and finishing operations.

Vertical integration can help cut costs, improve margins and prevent delays across production. Similarly, consolidation of players across the supply chain has added to the deal-making. In Italy, Gruppo Florence was formed in 2020 to create a production network comprising more than a dozen small and medium-sized luxury specialists, from hat makers to jersey makers. Such deals are expected to continue in 2023.

Investments and partnerships can also foster industry innovation by connecting brands and manufacturers with innovative fabric and yarn suppliers to help bring new textiles to market. For example, athleticwear brand Lululemon’s anti-odour Silverescent fabric is the result of a partnership with materials company Noble Biomaterials. This can also enable new materials to scale. Fashion group Inditex announced in May 2022 that it had agreed to buy 30 percent of Infinited Fiber Company’s production of its textile waste fibre each year for three years, facilitating Infinited’s plans to set up its first large-capacity factory.

Several brands have prioritised sustainability-related innovation, using partnerships with fibre producers to bring recycled or circular materials to market. H&M partnered with another Swedish company — textile recycling innovator Renewcell — in 2020 to incorporate more recycled fibres into its products. Similarly, US brand The North Face works with Finnish sustainable textile material company Spinnova to source its circular fibre made from wood and waste. To scale these materials, manufacturers will need to modernise their operations in tandem and in partnership with brands.

In the luxury segment, where labour can be more skills-based than in other segments, brands have secured access to craftmanship through manufacturer acquisitions. For example, Italian sneaker brand Golden Goose announced in October 2022 that it would acquire its main supplier of seven years, Italian Fashion Team, and LVMH-owned Fendi said it has taken a majority stake in Italian knitwear maker Maglificio Matisse. Since 2015, Chanel has acquired eight manufacturers, including Italian knitwear supplier Paima. While providing the French luxury label with greater certainty in terms of supply of materials, the acquisition strategy also grants Chanel greater access to innovation.

Closer to Home

Another shifting dynamic in fashion’s supply chains involves nearshoring. By moving manufacturing closer to consumer markets, brands can increase their speed to market while reducing the cost of transport and duties and mitigating various risks, including those related to inventory.

In 2020, MAS Holdings opened a manufacturing facility in Kenya so that the business could take advantage of the preferential trade agreements (AGOA) in place with the key consumer markets of the brands it serves; the facility manufactures apparel for PVH Corp., which owns brands such as Tommy Hilfiger and Calvin Klein. Meanwhile, South Korea’s Sae-A Group has opened two spinning mills in Costa Rica, the most recent in 2022, citing the political and social stability of the region as its appeal.

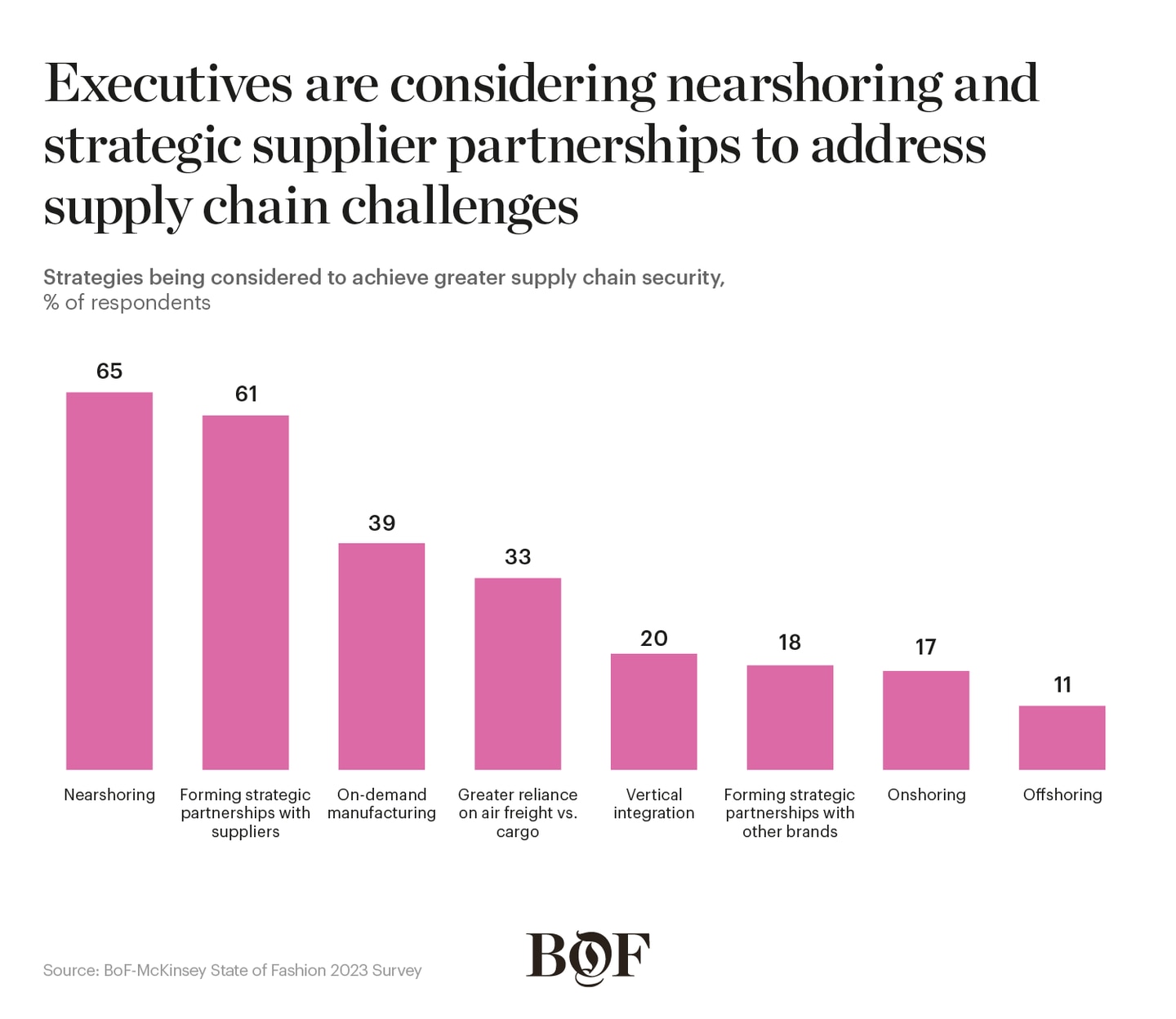

Many fashion players are expected to continue to produce garments in historically low-labour cost manufacturing countries such as Bangladesh and Pakistan, but nearshoring will remain on executive radars. In the BoF-McKinsey State of Fashion 2023 Survey, 65 percent of fashion executives said they were considering nearshoring to address supply chain challenges.

These shifts are creating new manufacturing hubs dedicated to serving US and European demand. In McKinsey’s annual survey of chief purchasing officers, over 75 percent of North American respondents said they expected to increase the share of sourcing from Central America, while more than 35 percent expected to increase the share from Mexico. In Europe, Turkey is emerging as the preferred closer-to-home hub, with 85 percent of Western European respondents expecting to increase their supply from the country, followed by Eastern Europe and Northern Africa.

Spanish brand Mango has said it will move some production in China and Vietnam to Turkey, Morocco and Portugal, while US footwear brand Steve Madden moved half of its production from Vietnam to Brazil and Mexico in 2021. In Brazil, footwear exports jumped 32 percent year on year in 2021. Similarly, the value of denim imports to the US from Mexico increased 50.58 percent in the first eight months of 2021, compared to the same period the prior year.

Sourcing from closer-to-home locations can create environmental benefits, too, for instance by reducing greenhouse gas emissions and energy use, as well as unlocking access to more sustainable materials and improving water stewardship. With more than 70 percent of the industry’s greenhouse gas emissions generated from upstream activities, some manufacturers are aiming to decarbonise manufacturing and leverage their improved sustainability credentials to differentiate themselves from the competition.

Nearshoring can be challenging to get right, however. Because raw materials suppliers are located close to traditional production regions, moving production nearer to home for many Western brands can make it difficult to source materials. For speciality manufacturers, like dyers and fabric makers, a location’s lack of technical skills can also be a concern. Manufacturers will need to rethink their processes to make nearshoring successful; simply moving operations will not be effective.

While rare, some fashion brands are investing in moving some production to their domestic markets. Boston-based sportswear label New Balance opened its fifth manufacturing facility in the US in 2022 and has promoted “Made in USA” collections.

The uncertain economic environment may prompt brands and manufacturers to postpone or downsize nearshoring strategies in the short term, given that manufacturing hubs in Asia are expected to remain significantly cheaper than other locations. It should be noted that nearshoring can also threaten economic prosperity and job creation in traditional manufacturing hubs, which would be negatively impacted if their manufacturing activity were to diminish. Brands should understand the full scale of its decisions and work with manufacturers to pursue nearshoring with good governance and ethics top of mind.

Building Responsiveness

Regardless of how suppliers diversify production capabilities or global footprints, increased digitisation will enable them to support the changing needs of brands. In a 2021 McKinsey survey, apparel chief purchasing officers cited capacity planning, virtual sampling and supply chain transparency among the key areas for digital investments in the next five years.

In pre-production, digital platforms are helping brands source fabrics and create digital samples, saving time and money and reducing waste. In post-production, digital looks are facilitating quality control and improving the flow of information between suppliers and brands.

While these innovations are modernising discrete parts of the value chain, linking them together in a digitally integrated journey remains a challenge. However, new platforms are emerging that digitally connect key parts of the production process. In China, Alibaba manages a manufacturing platform that connects shopping demand on sites Taobao and TMall with production information. Consumer insights are gleaned from its website, where AI algorithms and cloud technologies provide real-time analytics that manufacturers can use to streamline production and optimise inventories. Similarly, fast-fashion player Shein designs and manufactures products in small batches using a trend-prediction model and monitors performance in real time to adjust production up or down accordingly.

Some fashion brands are looking for suppliers that can accommodate small-batch production. The requires manufacturers to invest in capabilities like 3D sampling, automated sewing and knitting, 3D and digital printing, direct-to-fabric and direct-to-garment printing, as well as automated post-production logistics to finalise orders.

In terms of the adoption of automation, the fashion industry lags other sectors, such as electronics and auto-making. However, suppliers that make a case for investing in automation will be able to differentiate themselves from competitors by facilitating faster and smaller-batch production. More than 50 percent of chief purchasing officers said they expect automation to become a major driver for sourcing decisions by 2025.

In the year ahead, both brands and suppliers should prepare to work more collaboratively than they have in the past, moving away from transactional relationships to deeper partnerships that enable both parties to benefit from innovations and mitigate risks. About 60 percent of fashion executives in the BoF-McKinsey survey said they considered forming strategic partnerships with suppliers to mitigate supply chain disruptions. Collaboration can come in many forms, from co-financing and capability sharing to rewards and other incentive systems.

While manufacturers are likely to be cost-conscious in 2023, developing capabilities for nearshoring, small-batch production and digital production processes will help them establish a competitive advantage and will make them less reliant on price as a bargaining chip in building relationships with brands.

This article first appeared in The State of Fashion 2023, an in-depth report on the global fashion industry, co-published by BoF and McKinsey & Company.