STRATHAM, New Hampshire — Nestled in a corner in Timberland’s 246,000-square-foot headquarters, there is a room filled with dozens of industrial shoemaking machines: injection moulding machines, 3D printers, laser cutters and more.

These are apparatuses common in factories, helping manufacturers pump out hundreds of products every day. Here in Stratham, however, this miniature workshop installed a little over a year ago serves a different purpose: it allows Timberland to be closer to its customers by cutting down the time it takes to create a sample of a new style.

Before the existence of this workshop, dubbed the Shed, designers would send elaborate tech packets, or shoe design patterns, to the brand’s factories overseas. The factories would build the initial prototype, shipping it back to headquarters, which would then tweak the design and pass on the feedback. This back-and-forth, which the product team used to refer to as the “relay race,” would last for weeks before a style went into production.

With The Shed in place, that process has been cut down to a matter of days — even a single work day if a designer has a sketch ready.

This type of home-turf sampling capability is rare in apparel, and even rarer in footwear. But by reducing the lead time for new products, Timberland is hoping it can speed up the rollout of innovations and new creative directions beyond its signature wheat-yellow work boot.

This strategy, alongside a global marketing campaign, is critical to the brand’s plan to break free from a decade of largely flat sales, during which historic best sellers carried the company. As it approaches its 50th anniversary, Timberland is banking on the right mix of newness and heritage to bring energy to its name again, including expanded apparel offerings and more products aimed at women, as well as leveraging collaborations and launching innovative products to create excitement.

It won’t be easy. Timberland’s core customers today are very much fragmented: a mix of outdoor enthusiasts who want an eco-friendly footwear option, workers who need durable boots and shoppers who wear Timbs as part of their everyday wardrobe. Timberland makes products for all of these cohorts and more, from steel-toe work boots that offer protection from electrical shock to puffer jackets that come in “cameo rose” and leopard-print boat shoes in collaboration with the Japanese streetwear brand Wacko Maria.

As a result, the identity of the brand can come off as muddled. In an attempt to bring some cohesion to the sprawling product lineup, last year Timberland launched a campaign called “Built for the Bold” — an abstract but catchy slogan it hopes will resonate across its diverse customer base.

“What we are trying to do is continue to evolve with our consumer,” said Susie Mulder, who became global brand president of Timberland in April 2021. (VF Corp. bought the brand in 2011.) “A big part of the work we’ve done in the last two years is really zeroing in on who our true consumer is [and] what the brand stands for.”

Timberland’s ambitions are modest: mid single digit growth between the next three to five years. That would count as an improvement. While sales rose 20 percent off their pandemic lows, to $1.8 billion in the year ending March 2022, they remain below pre-2020 levels and far below the $3 billion in annual sales VF Corp. predicted for the brand in 2014.

For a long time, Timberland was “stuck in a limbo,” said Laurent Vasilescu, retail analyst at BNP Paribas. “But its aspirations today are grounded … and it will be driven by marketing and product innovation.”

The Timberland Story

Timberland’s rugged, outdoor branding runs deep, but it’s had a tumultuous relationship with its role in fashion and culture.

The company had its start in 1952, when shoemaker Nathan Swartz purchased the Abington Shoe Company. Years later, Swartz and his son Sidney became the first to utilise injection moulding technology to bond the outsoles of a boot to its uppers, creating a waterproof effect. Their seam-sealed, silicone-injected leathers also ensured the boots were fully waterproof — the first of its kind.

They called it the Timberland boot, and following its success, renamed the company to Timberland in 1978.

In the early 1990s, the brand became, seemingly overnight, a style staple in hip-hop culture. The 6-inch yellow boot — affectionately, “Timbs” — emerged as a streetwear sensation, worn by the likes of The Notorious B.I.G., Tupac, Nas and Wu-Tang Clan, and appearing in their lyrics too.

But in a 1993 interview with The New York Times, then-CEO Jeffrey Swartz, the grandson of Nathan, dismissed the brand’s new urban clientele as a flash-in-the-pan moment for the company, adding that its primary customer was “honest working people” who purchase Timberlands for their practicality.

The article prompted outrage among Black consumers. To repair its image, Timberland poured money and resources into urban nonprofit organisations like City Year (with which it already had a relationship). It invested profits toward community service and inner city youth engagement programmes, and offered paid time off for employees to volunteer. Today, Timberland very much embraces its role in hip-hop culture.

As part of its 50th anniversary activations this year — the first Timberland boot launched in 1973 — the brand will launch a “Hip-Hop Royalty” boot spearheaded by designer Chris Dixon, who is also the founder of CNSTNT:DVLPMNT, a small organisation that links students with professionals in creative fields. Together, Timberland and Dixon will host youth design workshops in key cities along the I-95 corridor, in communities that championed Timberland in its rise to hip-hop fame decades ago.

In 2011, VF Corp. purchased Timberland in a deal that valued the brand at $2 billion. Initially, sales grew steadily under the retail conglomerate, which also owns The North Face and Vans.

At the time, the fashion cycle had favoured boots, according to Vasilescu, who has covered Timberland since 2011.

What VF hadn’t known was how quickly the cycle would end. Sneakers became the dominant footwear category in the 2010s. Timberland remained heavily reliant on its original hero product: the 6-inch boot and its variations make up 28 percent of Timberland’s total sales.

In 2018, Timberland hired British designer Christopher Raeburn, known for using surplus materials in his streetwear collections, to be the first-ever creative director for the brand. Last year, however, Raeburn transitioned into a “collaborator-at-large” role within the company.

The Next 50 Years

Today, renewed interest in boots among consumers may be a tailwind for the brand.

But Timberland isn’t banking on trends alone. Beyond on-site sampling, the company has created a whole new corporate organisation that merges the creative side of the company with its engineers under Chris McGrath, who was named VP of global footwear design in 2019. (His new title is VP global product design and development, footwear and apparel.)

In addition to the product development team, McGrath, a former Nike designer, oversees the ACE team, which stands for advanced concepts and energy and was developed in 2020. This team is responsible for collaborations, such as a recent tie-up with Jimmy Choo, as well as less formal projects that invite both consumers and fellow shoemakers to collaborate with Timberland on new styles. Every year, Timberland hosts a multi-day workshop called CONSTRUCT: 10061 in which footwear creatives and innovators sketch, refine and ultimately make several shoe styles for Timberland.

Of 36 styles created last year, for instance, five are now being produced globally as part of the brand’s official line.

The ACE team also created the innovation behind the Timberloop collection, a line of products that are completely recyclable because the varying parts that make up the shoes can be disassembled based on material.

While Raeburn’s specialty in sustainability helped shape Timberland’s new creative vision, McGrath’s team evolved to ultimately lead the brand’s design direction.

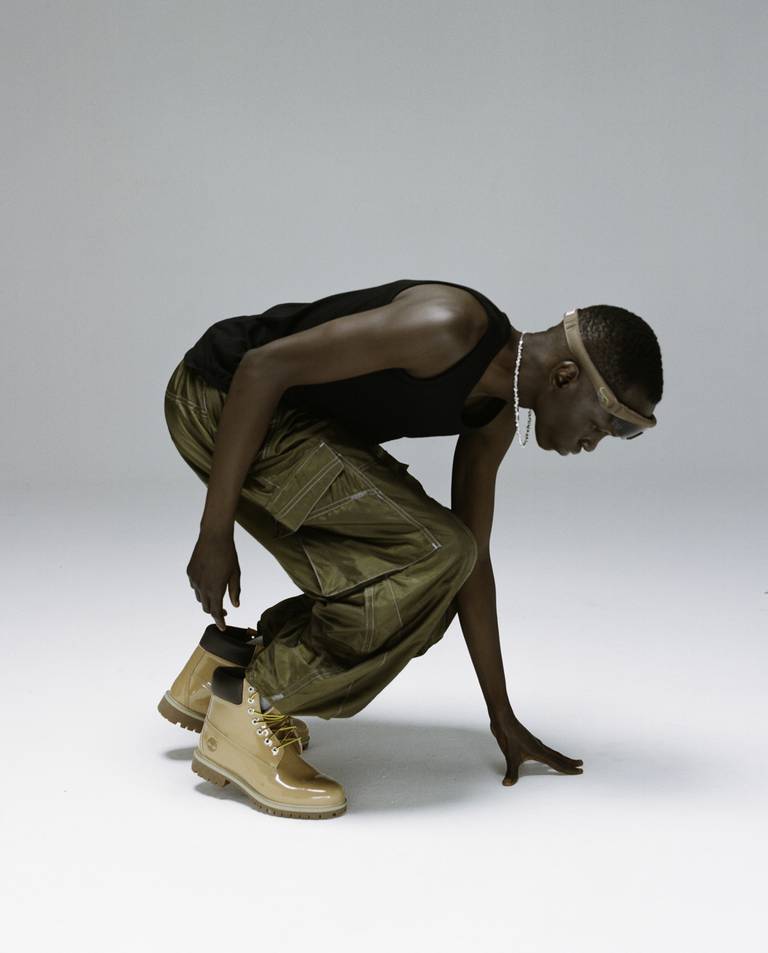

As part of its 50th anniversary kickoff, Timberland is also introducing a capsule collection of its 6-inch work boot reimagined by other designers, including Raeburn, Samuel Ross of A-COLD-WALL* and Opening Ceremony cofounder Humberto Leon. Later this year, it will open a new flagship store in New York City.

Even so, Timberland has actually reduced the number of overall styles by 32 percent since 2019, focussing on fewer but more precise products that consumers actually want and align with its historical DNA.

“We had a number of products that fit everyday life but without an interpretation of work or the outdoors,” said Mulder. “[Today] our lifestyle products need to fit into one of those two categories of our heritage.”

McGrath, who came to Timberland in 2019, plays an integral role in Timberland’s reinvention, Vasilescu said, alongside Drieke Leenknegt, Timberland’s chief marketing officer who effectively wrote the playbook on sportswear collaborations during her years at Nike, most recently as its global VP of influencer marketing and collaborations.

Timberland is especially focussed on expanding its share in the apparel category as well as among female consumers — feasible goals considering the slow, tempered growth that the company is aiming to achieve.

But Mulder may have bigger ambitions.

“Is Timberland in your closet?” she asked this reporter, knowing the answer was no.

“There’s the goal,” she said.