Empty nest syndrome, the sense of loss and emptiness many parents feel when their children leave the family home, is one of those transitional moments in life that is increasingly being deferred. Figures released from the 2021 census show that there is a notable increase in adult children living with their parents.

Two years ago there were 13.6% more family homes containing children over 18 than there had been in 2011. Or put another way, there were 4.9 million adult children living with their parents, an increase of around 700,000 on the previous census a decade earlier.

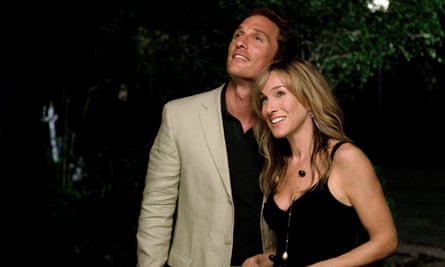

In popular culture the scenario of an adult child living with parents is almost always the subject of comedy. From Ronnie Corrbett in the 1980s sitcom Sorry! to films such as Failure to Launch or Hello I Must Be Going, the adult children are the oddballs that lend novelty to familiar romcom themes. And in the TV show Schitt’s Creek, they are symbols of entitlement and detachment from the real world. In reality, however, as a consequence of housing shortages, high rents, and changing relations between parents and children, it’s a common situation that is often less than amusing.

“Let’s not underestimate how important the environment we live in is for our mental health,” says Gabriela Morris, a counsellor who sees a number of clients living with their parents, either as a means of saving money or as a safe haven after a failed relationship or marriage.

She is aware of the tensions that can rise when adults from different generations with different expectations from life find themselves sharing a home, and the added restriction of familial bonds.

“Parents are always going to see their children as their children, no matter what age, and they often find it difficult to change the habit of trying to control their lives,” she says.

Many parents of today’s adult children benefited in their youth from a period that featured lower rents, no university fees, and a propulsive desire to escape the confines of their own parents’ more conservative households.

A generation of child-centred parenting has broken down some of the traditional power lines between elders and their offspring, creating a more egalitarian concept of the family, in which children’s needs and emotions have been taken more seriously. That reconfiguration has perhaps sapped some of the urgency that children once felt with regard to getting their own place.

Thirty or forty years ago, for example, only in the most liberal families were teenagers allowed to sleep with girl/boyfriends in the family home, a prohibition that inspired a passionate interest in car interiors, the back rows of cinemas and park benches. Nowadays banishment to such locations would be viewed by most teenagers as a grave infringement of their human rights.

But if more permissive parenting has lessened the impetus for those in their late teens and early 20s to share a damp house and terrible furniture with five friends, it doesn’t quite explain the growth in 30somethings who are co-habiting with their parents.

Office of National Statistics figures show that more than one in 10 of those aged 30-34 were living with their parents in 2021, about a 30% increase on 2011. While the raw data doesn’t tell the individual stories, it’s reasonable to infer that an effective exclusion from the property market has played a part in this trend.

It’s surely significant that London, where property prices are highest, has the largest proportion of families with adult children – more than one in four, and in some parts of the capital more like one in three, family homes boasts grown-up children.

Millennials have occasionally been known to look with a certain resentment at the good fortune their parents enjoyed in buying houses when such things were affordable for people who didn’t work in investment banking. But Morris doesn’t believe there’s any room in a multi-generational household for harbouring bitterness, or for exploiting parental guilt to claim a room.

“It’s not parents’ responsibility to compensate for the current housing difficulties,” she says. “Their task is to take care of their children the best they can until they become adults.”

Of course, exactly when a child becomes an adult is a moot point. The law says 18, while neurology suggests our brains don’t reach maturity until the mid-to-late 20s – whether that process is accelerated by leaving home or slowed by remaining has so far not been established.

Given that so many children do stay living with their parents until various stages of adult development, perhaps the key issue is how to make it work. Morris says it’s vital that both child and parent respect and embrace each other’s difference.

“Acceptance deepens the familial connection and helps prevent frustration and misunderstanding,” she says.

Parents ought to treat their children as adults, she advises, and by the same token the adult children should aim to contribute towards bills and food and the chores. Being honest about plans and intentions is also essential, she says, but ultimately the establishment of some house rules, as any self-respecting flatshares would seek to agree upon, might help head off conflicts.

With rare exceptions, even the healthiest parent-child relationship eventually needs space to thrive, for the children to realise their full independence, and for the parents to gain some later-life freedom from parenting.

Although there are cultures in which families frequently remain together down the generations, they’re also ones in which children feel most morally obliged to look after their parents in old age. So if parents begin to be expected to maintain a home for their children deep into adulthood, perhaps the quid pro quo will be the children having to deal on a day-to-day basis with infirmity, illness and dementia.

Now that really does sound like an incentive to leave home.