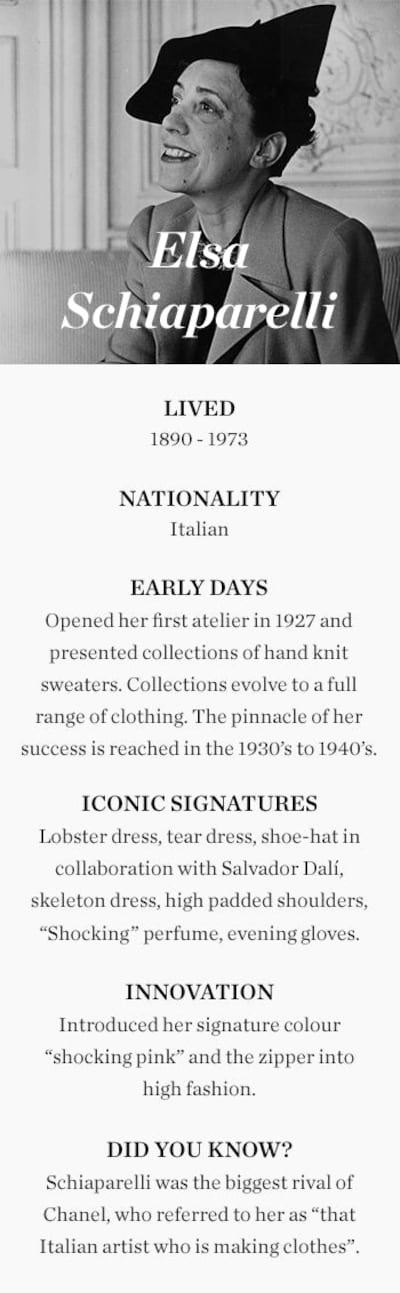

ROME, Italy — In the ‘20s and ‘30s, the great days of couture — it was generally accepted by those in the know that design sensitivity and even good business ability were not the only things to take a talent to the top. Guile, ruthlessness, opportunism and snobbery were also necessary: four boxes, all of which Elsa Schiaparelli effortlessly ticked. When Coco Chanel publicly referred to her as “that Italian artist who is making clothes,” it was not just a put down from the woman who had been queen until that point, it was a subconscious acknowledgement of the Italian’s almost immediate effect on fashion and, instead of destroying Schiaparelli, Chanel’s jibe determined that her rise to the top was not only inevitable, but speedy.

Elsa Schiaparelli came from an upper middle class, scholarly background. Born in Rome in 1890, she was influenced as a girl by the intellectuals and academics who visited Palazzo Corsini, where she was brought up. She was surrounded by beauty, sophistication and elegance. But she craved grandeur, glamour and wit. She found what she was looking for when still a girl, she saw the eccentric aristocrat, the Marchessa Casati, leading a leopard on a diamond-studded leash. The boldness and style of it never left Schiaparelli. In truth, she spent her whole life trying to create the Casati magic, not only in clothes, but also in her life.

The latter had many ups and downs. As a young woman, more instinctive than intellectual, she drifted on the edges of creativity. She fell in love with the Ballets Russes in Paris and more disastrously, with a Polish Count she met and became engaged to within 24 hours. When war was declared on Germany, the newlyweds decamped to the south of France and then to New York, where Elsa made friends with artists such as Picabia, Duchamp, Man Ray and Edward Steichen — the man often heralded as the father of fashion photography.

In Paris in the ’30s, Elsa Schiaparelli can be seen as a perky, colourful and irreverently entertaining feature of the fashion scene — the first couturier to make high fashion amusing by pointing out its funny side. Her approach bought notoriety in the form of dislike by the fashion establishment. But there was fanatical support by artists and intellectuals. Jean Cocteau attended her fashion shows. Salvador Dali created special items for her. As well as admirers, it is perhaps no surprise that Schiaparelli had her enemies. The exceedingly jealous and insecure Chanel especially disliked her and tried to dismiss her, but Schiap (as she was referred to) was too strong to be affected by such comments. Rather like a colourful, amusing parrot, she had a fun life, and made a lot of noise throughout it.

Wherever she went — and she lived a highly social life — Elsa Schiaparelli was news: she made sure of that. As Time magazine commented “Mme Schiaparelli is the one [of all the couturiers in Paris] to whom the world ‘genius’ is applied most often.” But it was not fashion genius or even creative genius. Her genius was in totally understanding not only the spirit of the age but also its creative manifestation in Surrealism.

In the true romantic novel style, Schiaparelli’s husband abandoned her with a severely depleted fortune and a baby daughter. In fact, she was almost destitute in her last weeks in New York . She was saved by a friend who paid for a passage to France for them both. Things were tough, but she felt at home at last. And very soon a chance meeting with Paul Poiret — at that point the father and Emperor of Parisian high-fashion — changed her life. In his salon with a friend, she tried on a coat. Suddenly the couturier appeared and gave it to her. By no means beautiful (‘jolie laide’ is the expression that fits her perfectly at this point), she had ‘esprit,’ she knew the rules of society — still remarkably tight in the ‘20s Paris — and possessed an appearance of assurance that many women of non-conventional looks and leaders of taste and style (Elsie de Wolfe, Daisy Fellowes, the Duchess of Windsor), also had in a world where prettiness meant nothing. Even faultless beauty frequently took second place to strength of character in the admiration stakes.

In this world Elsa Schiaparelli flourished. She sold fashion drawings to the fashion house Maggy Rouff, despite a directrice telling her she would be better employed farming potatoes. She sold to several second level couture houses also. In 1925, a rich friend bought a fashion house for her. A year later, she produced her first small collection which was photographed by the well known photographer George Hoyningen-Huene for the February 1927 edition of Vogue. Simply captioned “Schiaparelli,” they were sweaters influenced by the rigid lines of Cubism, even though their designer found Surrealism, the new and highly controversial art movement, much more to her taste. It was big news, and so was she. Schiap made it her business to be seen in the company of Picasso, Cocteau, Picabia and all the leading lights of Surrealism in nightclubs and cafes such as Le Boeuf sur le Toite as well as mixing with the top echelons of France’s artistic and creative aristocracy such as Vicomte Charles de Noailles and his wife, Marie-Laure de Noailles. Doors opened for her; not only for her sharp wit and good social background (neither of which Chanel had), but for her talent, lovingly husbanded by Bettina Bergery, the American model who became Schiaparelli’s public relations officer, one of the first in Paris and certainly the most influential.

Did she eclipse Chanel as the leader of the Paris fashion scene? Certainly in column inches. Her name was increasingly featured more than her rival’s, and she was known across the civilised world as symbolising daring, wit and stylish glamour — surprisingly perhaps, considering her Italian background. She was the epitome of French chic, initially largely based on her own way of dressing, but more powerfully by her extraordinary fashion shows, her global tabloid presence, and her wealth.

It was, of course, Shocking, the perfume inspired by Schiaparelli’s 1937 visit to Hollywood where she met Mae West — at that time probably, along with Garbo, the most famous cinema actress in the world — that made her a really wealthy woman. Schiap was fretting over the great perfumes that other female designers in Paris had introduced — to hugely successful sales. Chanel, of course, had No 5; Lanvin had Arpege — not to mention Joy, by the male couturier Patou. As we would say today, Schiap, as a shrewd businesswoman, knew she was missing a trick.

She had designed films costumes for Hollywood and had dressed the Studio System’s big bucks female stars of the time including Marlene Dietrich, who loved the high padded shoulders Schiap was designing as part of a super sophisticated, feminine adaptation of traditional menswear. At this time Salvador Dalí, the artist best known then and now as the epitome of Surrealism, was working closely with Chanel. But, independently, he had become fascinated by Mae West’s appearance. He designed a sofa based on the actress’s lips and having been in on all the discussions, it was offered to Schiaparell. But it was made in red and she wanted it in pink, so she declined the offer.

But she didn’t forget Mae West’s figure, which made a magnificently feminine contrast to most of Hollywood’s leading ladies. So she jumped at the opportunity of dressing the star for “Every Day’s a Holiday,” which, being set at the turn of the century, meant costumes that would exaggerate her voluptuous figure.

She called the perfume “Shocking”. It caused a sensation around the world and became an instant best seller, as did a dress based on it, which had air pockets inside the bodice that could be blown up to create the authentic West bust. Shocking can truly be seen as Schiaparelli’s equivalent of the “New Look” for Dior. It made her a household name. She had begun her reign as the most important and sought-after couturier in Paris; a world figure, a very rich woman and an influencer. In Hollywood films where costume designers like Adrian adapted her fashion attitudes for the needs of the screen. The only thing she could not control was the international political situation. In the late ‘30s time was against her. Europe was slipping towards war and America was soon to follow.

Schiaparelli had learned the art of making useful friends in New York and Paris, and although rich, she was no stranger to the privations of poverty. She knew the sound of rats scuttling across the bedroom. So she knew how to cope in occupied Paris if she had to. But, she used all her influential friends to ensure that she would not have to. Like Chanel, Schiaparelli lived an ambiguous life, not quite a collaborator but certainly ready to use the German occupation forces as and when she needed to get her way. Her high level contacts made sure that she had luxuries and privileges denied to the majority. When Paris had only seven licensed cars, she ran three. Her explanation was that she had special diplomatic immunities, but what was never clearly specified was whether they were granted by the American consul in Paris, or the Germans.

In June 1940, Walter Winchell, America’s most famous columnist, published a letter claiming that Schiaparelli was a spy. It was largely believed, even by J Edgar Hoover — head of the FBI — although never proven. And, of course, her Italian passport did her no favours. But she worked on raising funds for both American and French relief organisations before leaving Paris for America, where she remained for the duration of the war.

When she returned to Paris, things had changed. She had lost ground. It was no longer “Schiap” that was on everyone’s lips. It was Dior. He had taken her place as the darling of the international press and, although major publications still gave her coverage, it was much reduced. Was this punishment from a wounded country obsessed with the guilt of collaborators during the war? Had she stayed in America too long? Whatever the reason, Schiaparelli failed to recapture the heights she had enjoyed during the 30s.

But that does not negate her position in the pantheon of France’s greatest couturiers. Her influence on figures such as Yves Saint Laurent who claimed she “Trampled down everything that was commonplace….Her imagination was boundless,” and Jean Paul Gaultier, who has kept her iconoclastic spirit alive, makes a case for her as a founding figure of post ’50s modern fashion, in a way that many others, including Christian Dior, have not.

Of course, such a feisty woman fought back and managed to keep the house going by a number of commercial strategies. She made serious money from her licensing agreements ranging from underwear, to nail polish, and even to men’s sportswear and ties — not to mention the mattresses and shower curtains to which she gladly put her name. Schiaparelli was a good businesswoman — a sharp observer of society. As she said in an interview with The New York Times, “Life has changed…Even people with money aren’t spending it in the way they used to do’ and she even dismissed those as “a feeble minority!” The fact was that she had relied, certainly in France, on old money and, as she said at her return to Paris in 1945, the new couture clientele was “The newly rich wives of grocers, butchers and provision merchants.” And she hated what had happened.

In 1954, Elsa Schiaparelli finally closed her couture house which had been founded on three sweaters knitted by an Armenian émigré and had, from the beginning, sold handbags, scarves and gloves as enthusiastically as she tailored daywear and fabulous evening gowns. She was 60, a grandmother and tired. She brought a small house in Hammamet, which bought her much joy. The parties, the spectacular fancy dress balls that she always attended, were finished. She died in her sleep aged 83 on November 13 1973.

In a way Elsa Schiaparelli was working at the wrong time. Only she knew how to capitalise on the huge power of surrealism, only she was friends with all the artists, from Marcel Vertes to Salvador Dalí, and only she worked with them to produce witty fashion that dominated Paris in the ‘20s and ‘30s. But what she learned was that what amuses one generation is rarely really right for the next one. Hats like shoes or a mutton chop; fastenings like paperclips, fairground motifs, jackets with drawers for pockets don’t amuse forever. In fact, they were largely publicity stunts and, inspired as they were for attention — they were nothing more than a soufflé that fashion historians have allowed to overwhelm the basic reliable roast beef of Elsa Schiaparelli’s genius.