Anabel Maldonado knows what she likes. A certain e-commerce site she shops at regularly, however, does not.

“I feel like I should just never see gingham or checks or floral print or denim jackets and things that I’ve never shown interest in,” she said. “Instead, I’m having to literally go and filter 20 brands that I like and a bunch of colours that I like … I’m trying to whittle down and curate on my own.”

In her view, that’s not how it should be. Maldonado is the founder and chief executive of Psykhe, a “personalisation-as-a-service” platform for retailers that tries to understand shoppers’ tastes and recommend products using artificial intelligence and psychographic profiles built from their behaviour. A customer who browses Rick Owens is more likely to exhibit what Maldonado calls “high openness, high neuroticism” than one perusing Tory Burch, so if they were to go explore fragrances later, the algorithm would understand there’s a greater chance they’d be drawn to dusky oud than sunny florals and surface those scents in real-time.

The start-up, which said its customers include Altuzarra, Farm Rio, Pacifica Beauty and Kirna Zabete, is trying a novel approach to a problem that’s plagued retailers since the advent of e-commerce: Without the benefit of a sales associate who can read a shopper and interact with them face-to-face, how do you help them find products they’ll like? That need becomes more pronounced as the retailer grows. Unconstrained by physical limitations like clothing racks and square footage, they can carry a vast inventory that offers shoppers endless options. But it also becomes overwhelming to sift through and diminishes any sense of curation, turning them into generic digital warehouses competing on price.

The problems inherent in this situation have entered the spotlight lately as retailers such as Farfetch and Matchesfashion have crumbled in recent months. Experts say their lack of curation was a primary cause, while the curation offered by retailers like Mytheresa, Moda Operandi and Ssense is a key factor in their survival.

A potential solution could be algorithmic personalisation, where the assortment a user sees is tailored to their individual tastes. The concept has been wildly successful in other industries. Spotify’s song-recommendation engine helped it become music’s dominant streaming service. TikTok’s rapid rise is due largely to its ability to hook users with its “For You” feed.

“You should be able to have a store that’s completely tailored to you — your taste, your size, your events, your lifestyle, the brands you like,” said Natalie Massenet, the luxury e-commerce pioneer who founded Net-a-Porter.

That store doesn’t yet exist. At many retailers, personalisation amounts to a carousel at the bottom of the page suggesting products that are visually similar to what a customer recently looked at or other items from brands they’ve searched. Even those ahead of the curve, such as Zalando, which asks shoppers their brand and size preferences to tailor its product recommendations and suggests items to go with past purchases, aren’t yet personalising at a level equivalent to something like Spotify.

The concept isn’t easy to implement in fashion, which deals with physical goods, not digital content. Still, it arguably presents a major opportunity — if it can be done right.

Knowing What Shoppers Want

Understanding what customers want and giving it to them is a simple idea but difficult to execute. To create its recommendations, Spotify starts to learn the relationships between songs by looking at which ones users frequently put in playlists together, it told the Wall Street Journal. It adds in metadata, such as the song’s release date and label, and runs audio analysis to rank characteristics such as danceability, acousticness, loudness, tempo, energy and mode, like whether it’s in a major or minor key. It examines the song’s lyrics, too, as well as adjectives used to describe the track in blog posts and articles online.

Spotify uses the information to build a multi-dimensional map of all the tracks in its library. Those positioned closer together are more closely related and thus probably appeal to the same listeners.

The technique isn’t unique to Spotify, but in fashion the method is tough to replicate. Part of what makes Spotify work is its huge song library, which has something for everyone. The fashion equivalent of songs would be inventory. But to maintain an inventory that size would be prohibitively expensive. It would also require cataloguing each product at the same level of granularity.

“Where I think it’s really hard is having all the data that you need to match the merchandise against the multi-dimensional space … of what the customer’s hyper-personalised preference would be,” said Holger Harreis, a senior partner at McKinsey and co-leader of its global data initiatives.

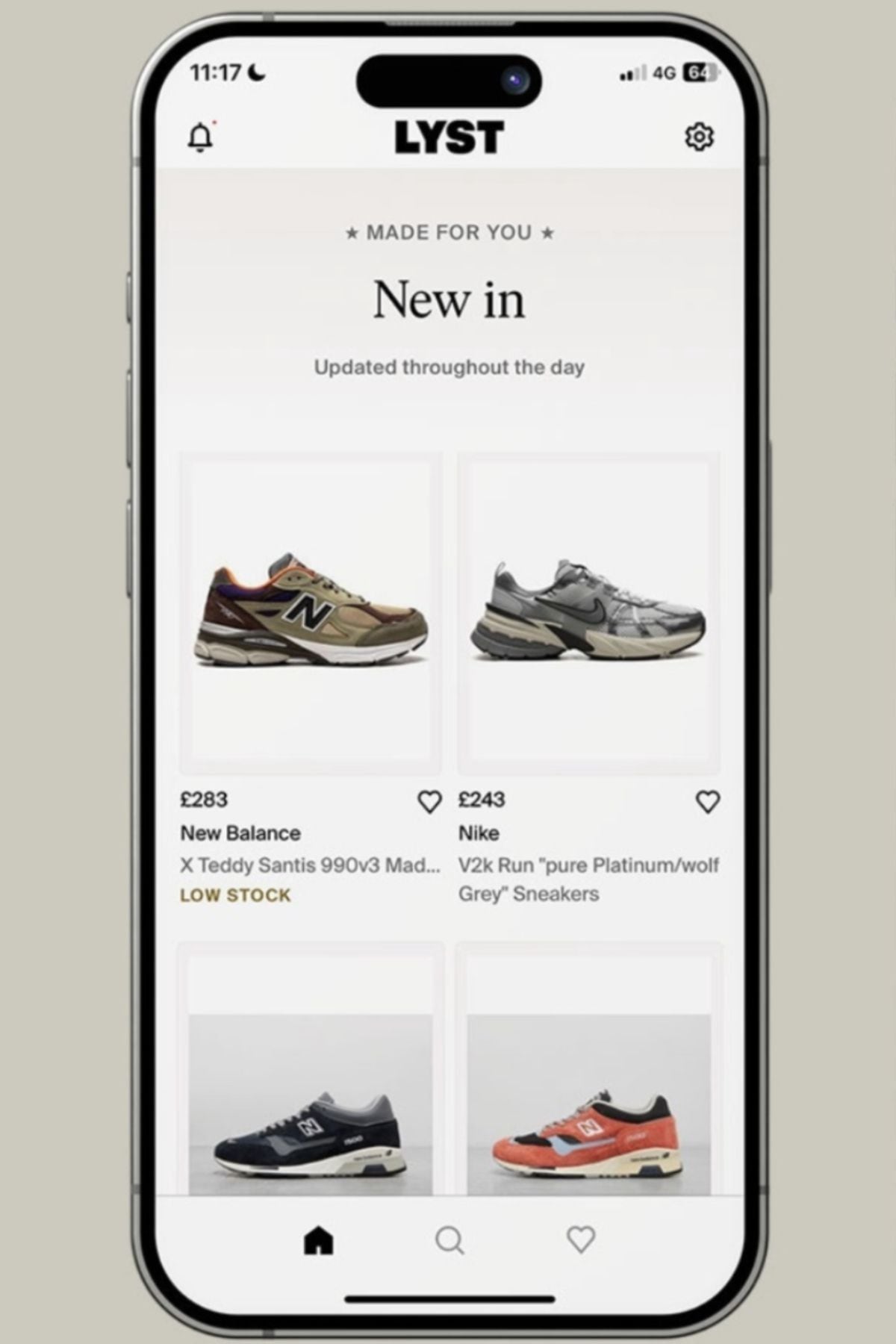

One company with its own version of the approach is Lyst, which acts like a search engine for fashion products offered by more than 17,000 retail partners. The company carries no inventory itself but charges a commission on sales through its site. It said it topped $600 million in gross merchandise value in its 2024 fiscal year. Because it effectively exists to help shoppers find what they want, it invests heavily in personalisation.

“At Lyst, we record and track absolutely everything that happens on our site,” said Anton Jefcoate, Lyst’s chief technology officer.

Each day it captures about 14.5 million data points, such as the amount of time a shopper spends on a page, how many times they scroll, the products they click on, what they put in their wishlist, the sizes they select and the colours they choose. Some are weighted more than others. Putting a product in a wishlist carries more value than scrolling, for instance.

The company gets product data from its partners but also uses a number of AI models to extract their characteristics. Similar to Spotify, it combines all this data into a kind of map, where each user and item is given a location in the form of a vector.

“It’s basically comparing your user vector against the vector of all the things in the database to find the closest match for a series of products,” said Jefcoate.

When shoppers browse Lyst, the products they see are tailored according to what Lyst understands about their tastes. The company conducted around 10 personalisation experiments in the past year and at best was able to boost conversion rates about 20 percent, according to Jefcoate.

Personalisation and Personalities

Whether this form of hyper-personalisation can work as well for every type of retailer or fully solve e-commerce’s curation conundrum is an open question. Massenet pointed out that shoppers look to higher authorities like editors and influencers for their cues on what to wear. Part of what makes some retailers successful isn’t just that they let shoppers easily find what they want but they also provide an educated opinion and a point of view. Otherwise you can wind up another nondescript outlet.

“You really need top-down curation with luxury products and fashion,” Massenet said.

Retailers also need to be mindful of how rigid their algorithms are. Psykhe’s Maldonado noted that surprise and novelty are important parts of shopping. If an algorithm is optimised strictly for conversion, its recommendations can be as stultifying and uninteresting as ones that aren’t relevant at all. In fact, Lyst has found weaving popular products into the results users see, even if they wouldn’t have appeared otherwise, to be effective.

“What customers really want — or at least what the numbers to tell us customers really want — is to have an element of personalisation in their product feeds but also be nudged and guided in the direction of other related but fresh start points,” Jefcoate said. “It’s not just about getting hyper-personalised. It’s about working out what the combination of ingredients is that really resonates with the customer.”

There may never be one Spotify of fashion. Not every Spotify user thinks its song recommendations are always on the mark anyway. But retailers are unlikely to go wrong by understanding what their customers want and trying to serve it to them. McKinsey’s Harreis said in his experience greater personalisation can increase conversion rates and reduce returns, which helps with profitability and has the added benefit of reducing the company’s carbon footprint.

Retailers just have to remember that sometimes what shoppers want is some guidance, too.