To show his latest collection, Ralph Lauren transformed a gallery at the Museum of Modern Art into a cocktail party in his living room, with guests seated around coffee tables and models occasionally pausing as if they intended to join the conversation. Though the evening was meant to evoke an exclusive New York gathering, the sort where Jessica Chastain and Mayor Eric Adams might rub elbows, the whole world was invited.

As more than one Ralph Lauren executive noted Tuesday, the brand no longer simply puts on fashion shows, it gives its customers an “experience.” Though the guest list was kept small, the show was streamed on the brand’s website and social media.

The goal, as always, is to cement in customers’ minds that Ralph Lauren is the purest expression of American luxury, even if that customer encounters the polo logo primarily while perusing racks of marked down collared shirts at a factory outlet.

That storytelling has real stakes. In 2018, with sales declining and Ralph Lauren’s cultural legacy rapidly fading into memory, the company laid out a detailed turnaround plan. There was much talk of higher-quality fabrics, rethinking wholesale and cutting headcount at corporate headquarters. But the strategy could be summed up simply: convince a new generation of consumers that Ralph Lauren clothes were relevant and worth paying full price for.

Four years in, the now not-so-new approach is starting to pay off: a growing contingent of younger customers are more likely to walk in the door of a flagship than an outlet (and share their trip to Ralph’s Coffee on TikTok). Sales are climbing, and the margins are fatter than they’ve been in nearly a decade. Still, the company isn’t ready to declare the mission accomplished.

“The brand elevation never stops,” chief executive Patrice Louvet told BoF. “In 20 years, we’ll still be talking about brand elevation.”

Fashion shows have played a big part in cementing that idea — fitting for a brand that created the American template for storytelling through fashion over decades of Western and prep-inspired world building. The 50th anniversary bash in September 2018, a gala held in Central Park that included Oprah Winfrey and Hillary Clinton among its guests, was arguably one of the few recent New York Fashion Week shows to achieve legendary status among insiders. Subsequent collections debuted against the backdrop of a bistro or nightclub, with production values and a guest list rarely seen outside Paris or Milan.

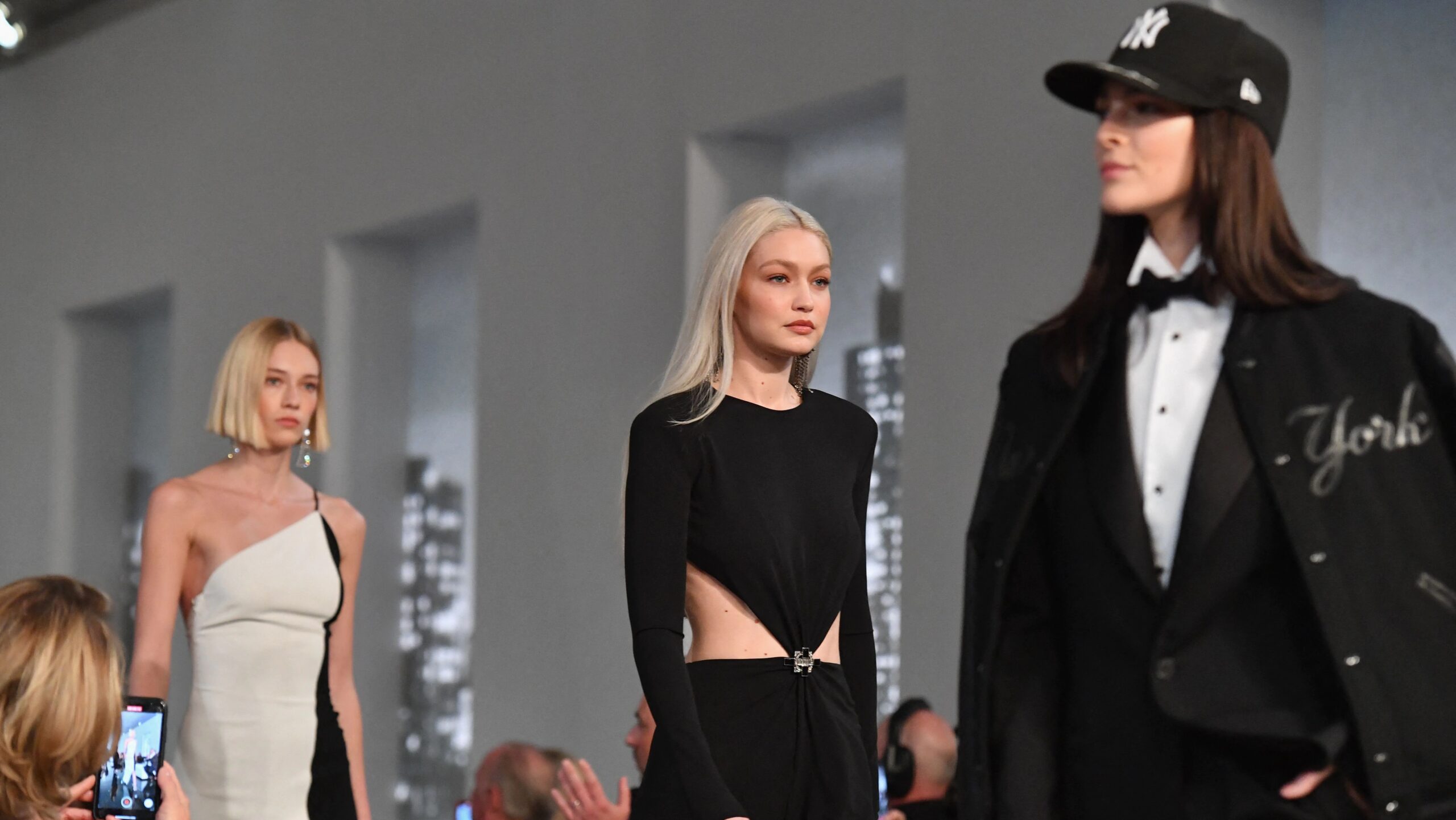

Tuesday’s show had many of the same hallmarks. Black-and-white furniture was arranged in neat lines throughout the small gallery. Tables were decorated with vases of red roses, a giant bowl of M&Ms and models of classic cars, perhaps a nod to the Fall 2017 show set at Mr. Lauren’s upstate New York garage. The clothes adopted a similar motif, with the occasional red coat or bow breaking up the parade of black and white dresses and tuxedos.

Certain looks amid the eveningwear and riding jackets shown Tuesday were clearly intended as catnip for Ralph Lauren’s hypebeast contingent, including a black New York Yankees jacket and the occasional appearance of the Polo Bear.

It’s a high-low mix that’s played a key part in Ralph Lauren’s turnaround (Mayor Adams, for one, cited the New York-themed apparel and a one-shoulder white dress sliced with a black panel as two of his favourites). The brand still sells plenty of polos, but it says it’s finding success in high-margin products that were not traditionally in the brand’s wheelhouse. In a February call with analysts, executives repeatedly flagged strong performance in outerwear, noting sales in the category had risen by 50 percent since 2018.

On its website, Ralph Lauren sells puffers and water-repellant jackets that slot easily into the gorpcore trend, handbags priced anywhere from $100 to nearly $30,000 and sneakers that range from chunky multi-coloured high-tops to minimalist white tennis shoes. An upcoming collection features fashion inspired by early 20th century style at historically Black Morehouse College and Spelman College, an effort to include some of those left out of the brand’s original vision of Americana.

“Ralph Lauren as a company appreciated that gone were the days of simply dictating what fashion was for America,” said Simeon Siegel, retail analyst at BMO. “As soon as the company started listening … that was what it took.”

The jury is still out on whether the young customers who have embraced the new Ralph Lauren will spend enough to replace the outlet mall bargain hunters, or if the elevated Ralph Lauren on display Tuesday has a ceiling. In 2018, the company predicted its refresh would boost sales by $1 billion. That is unlikely; fiscal 2022 revenue is projected to come in around $6.2 billion, better than expected but below pre-pandemic levels and a far cry from the $7 billion-plus of the mid-2010s.

Lower revenue partly reflects a partial pullback from department stores and outlet malls. The company opened four full-price stores in America in its third quarter, the most in six years. Another dozen are planned across North America over the next couple years. Sales in Europe are surging, thanks in part to new, luxury-oriented stores like a five-story flagship opened on Milan’s fashionable Via Spiga, which includes a restaurant serving “cuisine inspired by Ralph Lauren’s personal favourites,” including mini lobster rolls. The brand hopes concept stores in Shanghai and Beijing will herald similar returns in China.

All that means that while Ralph Lauren is selling fewer clothes, each sale is more profitable: aside from a brief plunge early in the pandemic, margins have risen steadily since 2018. Ralph Lauren has been able to raise prices, even before the recent bout of inflation: in its third quarter, the average price in the brand’s direct channels was up 18 percent from a year earlier, following a 19 percent increase the year before.

“Revenues are down meaningfully from their peak, they’re selling fewer units, and that’s a good thing,” Siegel said.

Still, the temptation to juice off-price channels must be strong. It may also be inevitable, if supply chain problems ease and the US market is suddenly flooded with all the clothing sitting in container ships off the Port of Los Angeles for the last year. Rising inflation means consumers will be more sensitive to the cost of clothing; they likely won’t care that Ralph Lauren was hiking prices for its own reasons well before it became an economy-wide trend.

To succeed in the long run then, Ralph Lauren needs to sell consumers on a compelling story that makes them forget about the price on the tag — because everyone, from the bargain hunters to the high rollers, is invited to the party these days.