“One of the greatest combinations of pasta and fish,” according to (the also great) Anna del Conte, the flavours of this Sicilian speciality reflect the turbulent history of Italy’s south. In her book Two Kitchens, Rachel Roddy tells the story of the ninth-century Byzantine commander Euphemism of Messina who, feeling peckish after landing near Marsala, tasked his cooks with making dinner from what they could find to eat there. “The hillside provided them with wild fennel, raisins and pine nuts, the sea with fish … a pleasing legend,” Roddy concludes, “which, whether true or not, ties the dish to a place and time, and reminds us of the riches that once thrived – and still thrive – in Sicily.”

The use of fruit and saffron suggests the culinary influence of the north Africans who displaced the Byzantines, but whoever’s responsible, they should be thanked for a flavour combination that Elizabeth David records as “discordant but exciting” – the perfect description for this deeply aromatic dish.

The fish

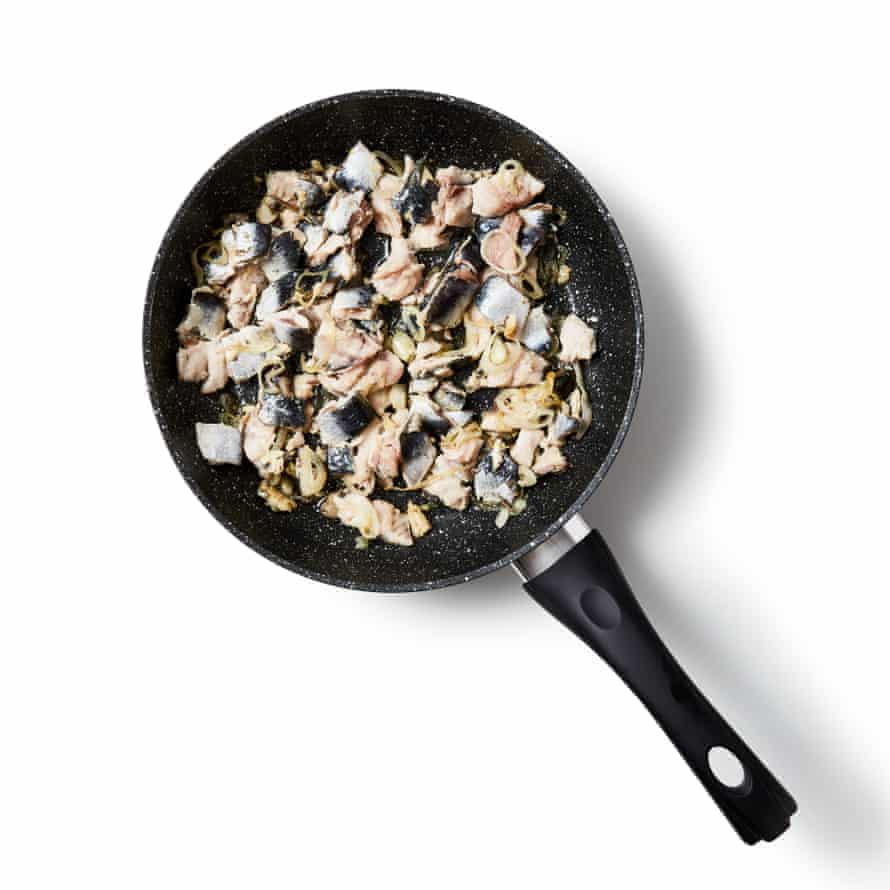

As the name implies, this dish is made with sardines, which is helpful, because we get such good ones in the UK in summer. Given their silvery beauty, I can see why both Alan Davidson, author of the magisterial Mediterranean Seafood, and del Conte choose to use some whole fish as a garnish, but seeing as they just end up mixed into the rest, unless you’re really looking to impress, I wouldn’t bother. (If you are, set aside one sardine per person, remove the head and spine, and fry in a very little oil until lightly golden on both sides.) That said, I don’t think you need to cut them up very small, either, as Davidson does with the remainder; most will break up in the pan anyway, but it’s nice to have some larger chunks in there to remind you what you’re eating.

Though she calls for fresh fish, Marcella Hazan laments in her Essentials of Classic Italian Cooking that, due to its “rare and unpredictable” supply, this “may have to be replaced by canned sardines”. I try this with sardines in olive oil, and the slightly salty, deliciously oily fish collapses so obligingly into the sauce that I almost prefer it, so they’re a great option if you can’t get hold of fresh fish.

Though less visible in the final dish, anchovies are almost as important for the intensely savoury quality they lend the dish, which, thanks to the dried fruit and aniseedy fennel, risks being rather sweet otherwise. Hazan cooks them above a pan of simmering water, and Davidson does so off the heat, but if you buy the kind packed in oil, rather than salt, they should melt happily into the rest without any such cosseting.

The fennel

Or, strictly speaking, fennel tops. As Roddy’s tale makes clear, this is traditionally made with wild fennel, a far hardier and more pungent affair than the stuff cultivated for its pallid bulbs. She relates seeing people gathering it on the riverbank near her home in Rome, and happily it’s also a common wild plant in most of England, and on coasts elsewhere in the UK; it’s said to have been introduced by the Romans – in fact, one website informs me it thrives to such an extent that it’s often considered “a pest”, clearly by people who’ve never tried pasta con le sarde.

There’s a healthy amount growing by the canal near me in north London, but if you can’t find any, or cultivated fennel with the fronds intact (farmers’ markets tend to be a better source than greengrocers or supermarkets), I wouldn’t bother using the bulb instead, as many recipes suggest, because it lacks the same intensity of flavour, and simply gets lost among all the other ingredients. A better idea is to stick in what fronds you can find, and then, like del Conte, add fennel seeds as well – you certainly can’t miss them. If you can’t find either, Stefano Arturi of the Italian Home Cooking blog tells me he substitutes dill, adding it raw at the very end.

“In traditional recipes, the wild fennel is boiled to eliminate some of the bitterness,” Roddy explains, though the 20 minutes recommended by the Silver Spoon feels excessive. It’s hard to be too prescriptive, given that everyone’s fennel will be different, but while I don’t think cultivated fennel tops, unless they’re particularly sturdy of stem, require even the briefest blanching before use, the five-minute boil in Nonna Fina’s recipe, collected in Anastasia Miari and Iska Lupton’s Grand Dishes, feels sufficient for the young, wild fennel greens I find. Adjust as necessary.

The aromatics

Alliums (I like Davidson and Nonna Fina’s shallots, but onion would be fine) give the dish an earthy sweetness, while dried vine fruits (I favour the diminutive currant) bring little pops of pure sugar; soak them before use, so they’re juicy, rather than chewy – like the crunchy, toasted pine nuts, they yield as much textural interest as flavour. Davidson and Hazan also use saffron, which gives the dish a touch of glamour, but this is very much optional.

The sauce

Roddy deploys homemade tomato sauce in her recipe, while Nonna Fina and Hazan both go for tomato puree, with the former also adding white wine and a pinch of sugar. Davidson and del Conte leave out the tomato altogether, though, which is also my own preference (as well as, according to several correspondents, the Palermo way of doing things), because I think it allows the sardines to shine, but if you’d prefer a wetter dish, dissolve a couple of tablespoons of puree in a little of the fennel cooking water and add it to the pan while cooking the sardines.

The pasta

This is one place where I would sanction the use of bucatini, the long, hollow strands that I generally find rather frustrating to eat in saucier contexts. Del Conte mentions rigatoni or penne, Roddy adds casarecce to the list, and Nonna Fina, though a fan of bucatini – “the hole running through the middle is perfect for catching the sauce” – allows that readers may pick whichever kind they prefer. Whatever you choose, cook it in the same water you used for the fennel tops – not only is this a good way to conserve both water and energy, but it ties the whole dish together.

To bake, or not to bake

Del Conte and Davidson both finish their pasta off in the oven, though the latter notes that “this is the practice at Trapani”, suggesting that in Palermo this stage would be omitted. I don’t care for it myself: it risks overcooking the delicate fish, and makes the dish as a whole rather dry and stodgy. Instead, I’d finish it with a good sprinkling of breadcrumbs – “a typical poor man’s substitute for grated parmesan”, as Genaro Contaldo puts it – and perhaps a lemon on the side, as Nonna Fina recommends, for people to add if desired. Buon appetito!

Perfect pasta con le sarde

Prep 10 min

Cook 45 min

Serves 2 (and easily doubled)

25g currants, raisins or sultanas

1 good pinch saffron (optional)

25g pine nuts

4 tbsp dry breadcrumbs

2 tbsp extra-virgin olive oil, plus a little extra to drizzle

Salt

½ tsp fennel seeds (optional)

250g fresh sardines (about 6), cleaned and gutted

About 40g fennel tops (see introduction), roughly chopped

2 shallots, peeled and finely sliced

4 anchovies in oil, drained and roughly chopped

175g bucatini, spaghetti, rigatoni or casarecce

2 lemon wedges (optional)

Soak the fruit in warm water. In a separate dish, soak the saffron with a tablespoon of warm water. Toast the pine nuts in a dry pan and set aside, then toast the breadcrumbs in the same pan with a good dash of olive oil and salt, until golden, and set those aside, too.

Grind the fennel seeds, if using.

Remove the heads from the sardines, carefully pull out their backbones and tails (watch a video online if you’re not sure how to do this), then roughly chop the flesh.

Bring a large pan of salted water to a boil and add the fennel tops.

If you’re using cultivated fennel, scoop out with a slotted spoon after 30 seconds, and drain; if using wild, simmer for about five minutes before scooping out. Cover the pan to keep the water warm for the pasta.

Heat the oil in a frying pan over a medium heat, and fry the shallots until soft but not coloured.

Add the anchovies, cook, stirring, until they’ve melted into the shallots, then turn up the heat slightly and add the ground fennel and sardine chunks.

Fry for a couple of minutes, then add the drained raisins, the saffron and its soaking water, and a spoonful of the fennel cooking water, and cook for five minutes more, adding more water if the mix becomes too dry.

Meanwhile, bring the fennel water back to a boil, and cook the pasta to your taste.

Add the fennel tops to the frying pan, then toss through the drained pasta, pine nuts and breadcrumbs, keeping a few breadcrumbs back to sprinkle over the finished dish, and serve with a lemon wedge on the side, if desired.