LONDON, United Kingdom — Fashion has a fake news problem.

Want to know how many people are employed in the industry, or where they work, or how much they get paid? How about the amount of clothing produced each year, and how much water is used to make them?

Good luck finding a definitive answer to any of these questions. The conversation around fashion’s social and environmental impact is riddled with vague claims and untraceable statistics. Most famously, fashion was labelled the second most polluting industry on the planet, a regularly quoted “fact” that’s been widely debunked.

The lack of good data is a major impediment to improving fashion’s record on climate change and improving conditions for millions of garment workers, advocates say. Opaque working practices and fuzzy definitions of sustainability provide cover for companies to engage in greenwashing, high-profile marketing that isn’t accompanied by real efforts to improve. They also make it difficult for even well-intentioned brands to choose the right suppliers and materials.

“If you can’t get the right data, you can’t get the right outcomes,” said Tamara Cincik, founder and chief executive of UK-based consultancy and industry lobby group Fashion Roundtable.

There are long-standing reasons why hard facts about the fashion supply chain are so hard to come by. For starters, many companies have little idea exactly how or where the materials used to make their clothes come from. Some companies do collect data from their suppliers, but they don’t always disclose it to the public, and when they do, it’s rarely standardised to make comparisons against competitors easier. In many cases, exactly what to measure, and how, remains a topic debate.

Sorting Fact From Fiction

There are signs things are gradually improving. A growing number of independent initiatives are working to provide better information to educate consumers and industry alike.

“To make concrete demonstrable progress we … need to help clear up the mushinesss that is sustainability,” said Maxine Bédat, founder and director of the New Standard Institute, a think tank that’s set out to demystify the subject. “It is still shocking to look up and see just how little is invested in the actual research before jumping to the conclusions that we should do X, Y and Z, or saying cotton is the best thing, or the worst thing.”

If you can’t get the right data, you can’t get the right outcomes.

On Wednesday, the organisation launched a roadmap providing guidance for consumers, media and the industry on how to navigate the current landscape, avoid misinformation and drive change. It lays out guidelines on how to read between the lines of media releases, critically explains the value of commonly-used standards, and provides a framework for a more fact-based approach. It’s accompanied by a six-part masterclass. Later this year, NSI is rolling out a fact-checking database that will score commonly-quoted facts based on how reliable their source is.

The NSI is part of an increasingly urgent push to provide high quality and accessible information about fashion’s impact to a broader set of stakeholders. While brands are struggling to understand the best course of action, consumers are equally confused, and increasingly wary of potential greenwashing. As the industry comes under more scrutiny from regulators, the need for good information is becoming even more pressing.

“If we are to make any progress when it comes to sustainability commitments what we need is traceability and transparency,” said Ayesha Barenblat, founder and CEO of nonprofit advocacy group Remake. “It’s not a silver bullet, but it’s the first step.”

Before Bédat ran NSI, she co-founded Zady, an early entrant into the ethical e-commerce space. She’d previously worked at the United Nations, concluding amid the frenzy of neoliberalism that characterised the early 2010s, that business could more effectively and swiftly drive change.

Though Zady was initially a platform dedicated to responsibly-sourced products, Bédat was frustrated by how difficult it was to find brands who knew enough about their manufacturing to really stand behind sustainability claims. The company launched its own private label to try and produce garments with a fully traceable supply chain and started publishing its findings.

“Brands much, much larger than Zady would reach out privately and say, ‘the information you’re sharing is so helpful for our team,’” Bédat said. “I was shocked, because I thought the average person didn’t know, but I assumed industry insiders did.”

She switched gears, deciding the best way to change things wasn’t to make more clothes, but to help fill in the gaping knowledge and research gaps within the sector.

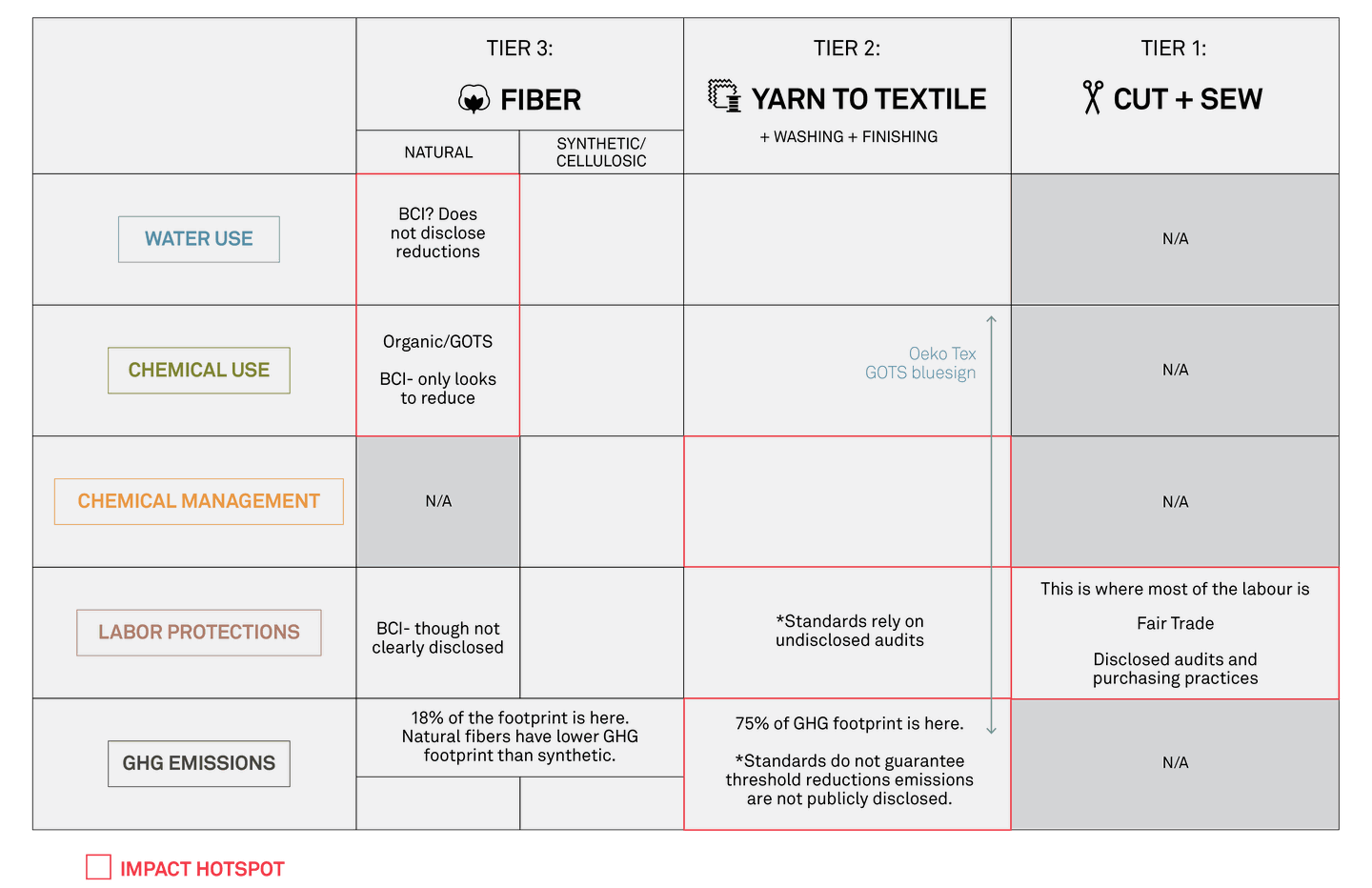

A roadmap to understand commonly-used standards | Source: NSI

It took Bédat two years consulting experts and combing through documents to build a robust fact-based and peer-reviewed curriculum for NSI. It’s a journey that took her to China, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka to gain a better understanding of fashion’s supply chains. She travelled to Ghana to research the fate of donated clothes, and to Texas where she met with cotton farmers. She worked with climate scientists and consumer psychologists, labour experts, toxicologists and agricultural scientists, as well as economists, political theorists and experts in intersectional environmentalism, which advocates for the protection of both people and planet.

“The industry intersects with so many things that, up until this point, have existed in silos,” said Bédat. Even now, hard truths remain elusive. “We’re not God, we don’t have that, but what we can say is, ‘this is a more reliable source, and this is a less reliable source,’” she added.

The Industry Joins the Effort

The industry is promising change, too. Last month, industry advocacy group Global Fashion Agenda and consultancy McKinsey launched a report analysing and quantifying fashion’s greenhouse gas emissions. The prognosis wasn’t good. Fashion makes up around 4 percent of global emissions, the report found. At its current trajectory, it’s set to blow past levels aligned with global goals to prevent catastrophic climate change by 2030.

The fact that this kind of baseline didn’t already exist is “alarming” said McKinsey senior partner Karl-Hendrik Magnus. The GFA will present the report to members of the UN’s Fashion Industry Charter for Climate Action later this month. The initiative launched in 2018 with signatories committing, among other things, to cut the industry’s emissions 30 percent by 2030, despite lacking a benchmark level.

It’s not a peer-reviewed academic report, but GFA and McKinsey said they sought to be transparent about their sources, consulted with experts and dedicated significant space to outlining their methodology.

Elsewhere, many in the industry point to the Sustainable Apparel Coalition’s Higg Index as a promising sign of progress. The widely-used suite of tools devised by the industry alliance promises a standardised and comparable set of measures for sustainability performance. According to the SAC, almost all the largest brands have assessed themselves using Higg tools, and it’s been used to collect environmental data from more than 18,000 factories.

“The fashion value chain is the most opaque, distributed, and outsourced of any product type in the world,” said Amina Razvi, SAC’s executive director. “For impacts such as how much CO2 the fashion industry emits, how many workers are employed by the industry, how much water this industry uses, these kinds of totals are elusive and continue to be, but we are getting closer to establishing better baselines.”

To be sure, such initiatives are not without their critics. They argue that the SAC and Higg Index are not transparent enough. It’s backed by the industry and companies self-report their data, which, for the most part, is not made public.

Without good data, you end up in greenwashing.

“The SAC gives the industry cover,” said Remake’s Barenblat. “It’s like Exxon measuring its fossil fuel footprint.”

The SAC argues that it’s a multi-stakeholder organisation, and academics, nonprofits, governments and other organisations have all contributed to developing and implementing the Higg Index. Many of its tools are open. Increasingly, brands and manufacturers can choose to share their results and there’s significant value in having a standardised set of metrics.

“There are many academically or NGO-derived measurement tools for the apparel industry, but most of these have failed to gain traction,” Razvi said.

Transparent and independently verified information matters, because data is powerful.

Over the course of the pandemic, Remake led a campaign to force companies to pay for cancelled in-production orders. The panicked pull back by many fashion companies has caused a humanitarian crisis as garment workers lost work and wages. As a result of the campaign, 21 brands have committed to pay in full for completed and in-production orders. Remake estimates it’s unlocked $1 billion for suppliers in Bangladesh and $22 billion globally.

“Pay up was so successful because we had really good data,” Barenblat said. Though many brands initially pushed back against the demands, it was hard to dispute the evidence of cancelled orders and their devastating financial impact.

As the issues surrounding climate change and global inequality become more pressing, ensuring there is access to robust information is increasingly important.

Without good data, “you end up in greenwashing,” Fashion Roundtable’s Cincik said. “So many people are drawn to social media, which is a series of opinions rather than facts… we clearly need experts, otherwise we’re just living in a world of fake news.”

Additional reporting by Rachel Deeley.

Related Articles:

[ How Fashion’s Sustainability Targets Measure Up ]

[ Will Fashion Ever Be Good for the World? Its Future May Depend on It ]

[ Exactly How Bad Is Fashion For the Planet? We Still Don’t Know For Sure ]