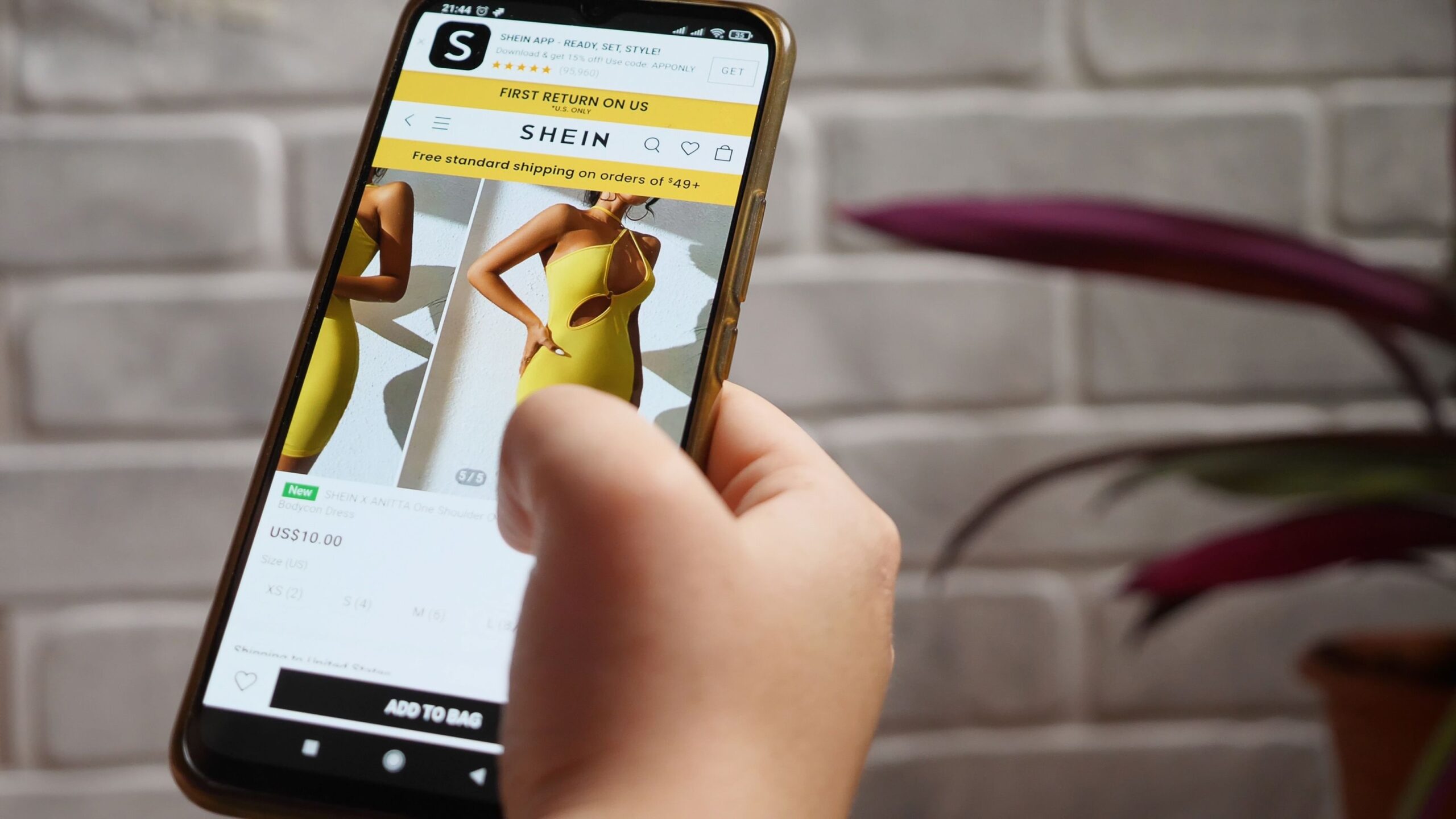

Between 2019 and 2021, Shein quadrupled sales, and at one point last spring, commanded a $100 billion valuation in a funding round, more than the market capitalisation of the owners of H&M and Zara combined. Allegations that the retailer’s clothes were shoddily made, that it mistreated workers, ripped off independent designers and that its business model was a disaster for the planet appeared to leave no mark.

Shein is no longer looking quite so invincible these days.

In the US, the Chinese fast-fashion retailer’s growth slowed dramatically starting in early 2022, according to data from Earnest Research, which tracks consumer spending online. In June, the company saw its first year-on-year sales decline since the pandemic. Sales then fell for five months before rising slightly in December. Last week, the Financial Times reported that Shein was raising funding at a $64 billion valuation — still enormous for an online fashion retailer but down one-third from its last raise.

There’s no one reason why some of Shein’s customers have moved on. In a slowing economy, some are spending less money on fashion. The infamous Shein hauls — big orders of clothes meant to be shown off on social media but only worn once, if at all — look increasingly out of step with the times. The negative publicity may have taken a toll. And Shein isn’t the only Chinese fast-fashion giant on the scene anymore; in November, Temu, a US app selling cheap clothes and other items launched that month by Pinduoduo, topped the Apple charts shortly after it launched.

Shein isn’t standing still. It’s opening warehouses and manufacturing hubs in the US and Europe, cutting shipping times to its customers. It’s launched a designer incubator programme and an initiative to cut its emissions by 25 percent. Far from hurting sales, a recession could increase fast fashion’s appeal to consumers worried about their finances. Shein will have plenty of cash to execute its plans: the Financial Times reported the company seeks to raise $3 billion and may be planning a US initial public offering later this year.

“We’re very excited about the direction of the business,” said Peter Day, global head of strategic communications and former chief privacy officer at Shein. “One of the beauties of our business model is that because we’re so aligned with customers on price, we see ourselves as being well-positioned in the macroeconomic environment.”

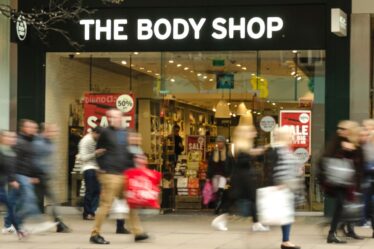

At the same time, Shein will need to show results quickly. The lifecycle for fast-fashion brands can be short: Forever 21 and Topshop are among the many low-price retailers that burst onto the scene practically overnight and faded just as quickly.

“They need to seriously ask themselves how is this fast-fashion model of theirs going to develop considering their younger generation of eco-conscious consumers,” said Jessica Ramirez, a retail analyst at Jane Hali & Associates.

A Less Eager Shopper

There are several key factors that account for Shein’s decline, according to analysts and industry insiders. For one, Shein’s Gen-Z, tech-savvy shoppers are simply spending less money on clothing, especially via e-commerce as the world opens up again.

“Folks who particularly had extra dollars in their pockets in 2021 and 2022 were low- or middle-income consumers,” said Sonia Lapinsky, managing director of AlixPartners’ retail practice. “In 2022, we saw compression in retail across the board, but it’s hitting this lower-income consumer much harder. Discretionary income is drying up so even the low prices [of fast fashion] are not low enough.”

And young customers, in particular, are not “glued to their computers and online shopping all day the way they were a year ago,” Lapinsky added.

As the novelty of Shein’s ultra-low prices faded, mentions of it swelled in conversations about its unethical business practices and alleged duplicates of others’ designs, according to Brandwatch, a consumer-intelligence firm. Between 2020 and 2023, about 70 percent of overall conversations regarding Shein on the internet skewed negative in sentiment.

Shein is “taking a lot of the brunt of criticism for the industry as a whole,” said Kellan Terry, head of PR and communications at Brandwatch.

The brand has its defenders, however.

“There is a moral debate being waged in Shein’s negative mentions,” Terry said. “Many people are citing questionable and ethical business practices by the brand and the consequences of fast fashion as a whole, but others are talking about lower-income people being able to afford and buy stylish clothing too.”

Younger consumers are especially susceptible to the opinions of their peers, said Ryan Nelson, a partner at Jobi, a venture firm that specialises in retail and technology.

“Shein is in the hot seat right now,” Nelson said. “That’s not to say in a couple of months or a year it won’t blow over.”

Bright Spots

Shein has addressed its shortcomings by investing millions of dollars in helping young designers launch their own lines in an incubator programme called Shein X. Last year, it also announced a plan to cut carbon emissions by a quarter by 2030 and introduced a resale programme that allows shoppers to sell their pre-worn Shein for store credit.

Whether this is enough to repair its public image remains to be seen.

“Their resale [launch] seemed like a marketing gimmick,” said Ramirez, with Jane Hali & Associates.

Other fast-fashion retailers have sought to portray themselves as sustainable. H&M and Zara-owner Inditex rank second and third, respectively, in BoF’s 2022 Sustainability Index out of 30 of the world’s largest retailers. H&M in particular has led the charge in materials and waste innovation with initiatives like pre-worn garment collection in its stores since 2013 and using textiles made from grapes, leftovers from food crops and organic cotton.

Last year, Shein launched a collection of pieces made of recycled polyester and “forest-safe” viscose fibre called EvoluShein. The company did not disclose how much of its overall assortment is made of more sustainable materials.

Shein is also in the process of opening two new distribution centres in North America this year, in addition to one in Indiana that opened last year, all of which will shorten its product delivery time to customers. The company is also reportedly exploring a marketplace model that would offer consumers not only its own branded pieces but products by other brands too.

Cultivating a more globalised supply chain and offering an even larger assortment of goods may be more effective strategies for growth ultimately.

These moves “will likely see Shein become even more of a competitor to the fashion segment,” Deutsche Bank analyst Adam Cochrane wrote in a recent note.