No need for more scare stories about the looming automation of the future. Artists, designers, photographers, authors, actors and musicians see little humour left in jokes about AI programs that will one day do their job for less money. That dark dawn is here, they say.

Vast amounts of imaginative output, work made by people in the kind of jobs once assumed to be protected from the threat of technology, have already been captured from the web, to be adapted, merged and anonymised by algorithms for commercial use. But just as GPT-4, the enhanced version of the AI generative text engine, was proudly unveiled last week, artists, writers and regulators have started to fight back in earnest.

“Picture libraries are being scraped for content and huge datasets being amassed right now,” says Isabelle Doran, head of the Association of Photographers. “So if we want to ensure the appreciation of human creativity, we need new ways of tracing content and the protection of smarter laws.”

Collective campaigns, lawsuits, international rules and IT hacks are all being deployed at speed on behalf of the creative industries in an effort, if not to win the battle, at least to “rage, rage against the dying of the light”, in the words of Welsh poet Dylan Thomas.

Poetry may still be a hard nut for AI to crack convincingly, but among the first to face a genuine threat to their livelihoods are photographers and designers. Generative software can produce images at the touch of the button, while sites like the popular NightCafe make “original”, data-derived artwork in response to a few simple verbal prompts. The first line of defence is a growing movement of visual artists and image agencies who are now “opting out” of allowing their work to be farmed by AI software, a process called “data training”. Thousands have posted “Do Not AI” signs on their social media accounts and web galleries as a result.

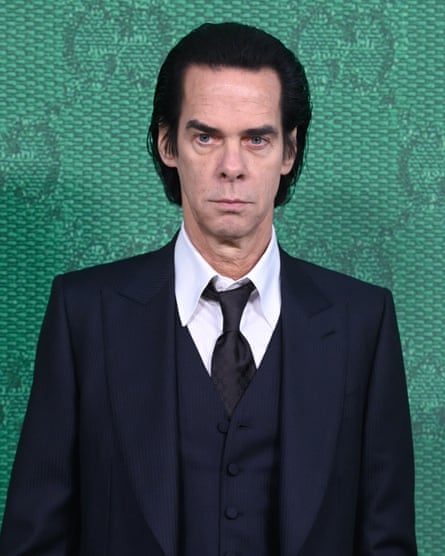

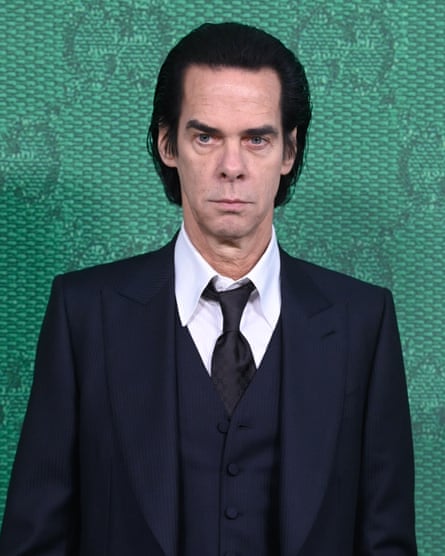

A software-generated approximation of Nick Cave’s lyrics notably drew the performer’s wrath earlier this year. He called it “a grotesque mockery of what it is to be human”. Not a great review. Meanwhile, AI innovations such as Jukebox are also threatening musicians and composers.

And digital voice-cloning technology is putting real narrators and actors out of regular work. In February, a Texas veteran audiobook narrator called Gary Furlong noticed Apple had been given the right to “use audiobook files for machine learning training and models” in one of his contracts. But the union SAG-AFTRA took up his case. The agency involved, Findaway Voices, now owned by Spotify, has since agreed to call a temporary halt and points to a “revoke” clause in its contracts. But this year Apple brought out its first books narrated by algorithms, a service Google has been offering for two years.

The creeping inevitability of this fresh challenge to artists seems unfair, even to spectators. As the award-winning British author Susie Alegre, a recent victim of AI plagiarism, asks: “Do we really need to find other ways to do things that people enjoy doing anyway? Things that give us a sense of achievement, like writing a poem? Why not replace the things that we don’t enjoy doing?”

Alegre, a human rights lawyer and writer based in London, argues that the value of authentic thinking has already been undermined: “If the world is going to put its faith in AI, what’s the point? Pay rates for original work have been massively diminished. This is automated intellectual asset-stripping.”

The truth is that AI incursions into the creative world are just the headline-grabbers. It is fun, after all, to read about a song or an award-winning piece of art dreamed up by computer. Accounts of software innovation in the field of insurance underwriting are less compelling. All the same, scientific efforts to simulate the imagination have always been at the forefront of the push for better AI, precisely because it is so difficult to do. Could software really produce paintings that entrance or stories that engage? So far the answer to both, happily, is “no”. Tone and appropriate emotional register remain hard to fake.

Yet the prospect of valid creative careers is at stake. ChatGPT is just one of the latest AI products, alongside Google’s Bard and Microsoft’s Bing, to have shaken up copyright legislation. Artists and writers who are losing out to AI tend to talk sorrowfully of programmes that “spew rubbish” and “spout out nonsense”, and of a sense of “violation”. This moment of creative jeopardy has arrived with the huge amount of data now available on the web for covert harvesting rather than due to any malevolent push. But its victims are alarmed.

Analysis of the burgeoning problem in February found that the work of designers and illustrators is most vulnerable. Software programs such as Midjourney, Stable Diffusion and DALL.E 2 are creating images in seconds, all culled from a databank of styles and colour palettes. One platform, ArtStation, was reportedly so overwhelmed by anti-AI memes that it requested the labelling of AI artwork.

At the Association of Photographers, Doran has mounted a survey to gauge the scale of the attack. “We have clear evidence that image datasets, which form the basis of these commercial AI generative image content programs, consist of millions of images from public-facing websites taken without permission or payment,” she says. Using the site Have I Been Trained which has access to the Stable Diffusion dataset, her “shocked” members have identified their own images and are mourning the reduction of the worth of their intellectual property.

after newsletter promotion

The opt-out movement is spreading, with tens of millions of artworks and images excluded in the last few weeks. But following the trail is tricky as images are used by clients in altered forms and opt-out clauses can be hard to find. Many photographers are also reporting that their “style” is being mimicked to produce cheaper work. “As these programs are devised to ‘machine learn’, at what point can they generate with ease the style of an established professional photographer and displace the need for their human creativity?” says Doran.

For Alegre, who last month discovered paragraphs of her prize-winning book Freedom to Think were being offered up, uncredited by ChatGPT, there are hidden dangers to simply opting out: “It means you are completely written out of the story, and for a woman that is problematic.”

Alegre’s work is already being misattributed to male authors by AI, so removing it from the equation would compound the error. Databanks can only reflect what they have access to.

“ChatGPT said I did not exist, although it quoted my work. Apart from the damage to my ego, I do exist on the internet, so it felt like a violation,” she says.

“Later it came up with a pretty accurate synopsis of my book, but said the author was some random bloke. And, funnily enough, my book is about the way misinformation twists our worldview. AI content really is about as reliable as checking your horoscope.” She would like to see AI development funding diverted to the search for new legal protections.

Fans of AI may well promise it can help us to better understand the future beyond our intellectual limitations. But for plagiarised artists and writers, it now seems the best hope is that it will teach humans yet again that we should doubt and check everything we see and read.