Luke and Lucie Meier’s daughter Ella Rose will be two years old in no time at all. Luke’s been buying a lot of classic jazz from the Blue Note back catalogue so Ella Rose’s childhood will have a formative aural backdrop. “When she hears a certain record, it will take her back,” says Luke. “And old jazz is a good start.” That’s how he was raised in Vancouver, with a mother who was a music nut.

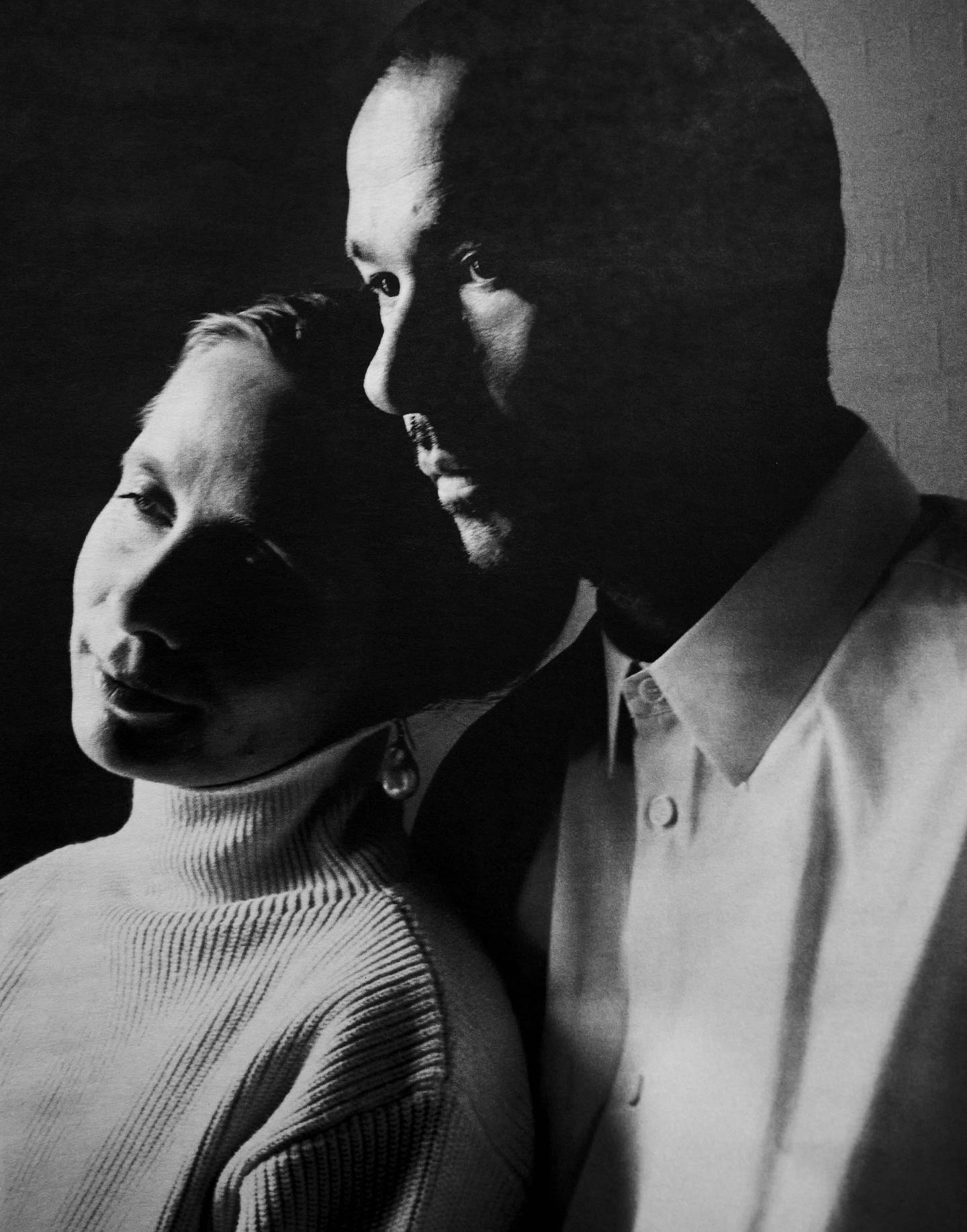

The past plays like that for the Meiers. Happy memories, which have filtered into the work the husband-and-wife duo are doing as creative directors of fast-growing Jil Sander. When Lucie was a child in Switzerland, her mother was a huge fan of Jil’s rigorously intelligent clothing. She still is, now her daughter and her partner are in charge of the brand. That’s no surprise. The Meiers have maintained the original rigour while they evolve their own personal dialogue with the brand. The conversation achieved a beautiful fluency with their most recent collection and the Milan presentation that showcased it in February.

“We wanted to push ourselves a little bit more, become a little bit less ‘expected’ with what we’re working on,” says Luke. “No matter what we do, the word ‘minimal’ seems to follow us along. There was always this expectation, you know, and we were happy to challenge that a little bit.” True, ‘minimalism’ is the albatross that has dogged all those who would carry the Jil Sander standard. Raf Simons complained about it too. But, just as he did, the Meiers have been infusing the brand with a subtle couture-inflected luxury. The obvious temptation would be to label it “quiet.” I won’t do that, because there is something quite grand, almost monumental, about what Luke and Lucie are doing.

Today, on a Zoom call, he’s in black, she’s in white. Not a deliberate choreography, he insists, but it immediately plays into preconceptions. Luke: shaven-headed, strict, the pragmatist. Lucie: long blonde hair, romantic, the dreamer. He talks, she comments, her interjections like a stream rippling through his words. They seem totally intertwined. I imagine them meeting in Florence in the year 2000 when they were students at the fashion college Polimoda, billeted in the same apartment, his music seeping through the walls. “The place was so small I couldn’t escape it,” she recalls. “But the way Luke talked about everything was just so interesting. And I was just really drawn into his world. I had no idea. He really opened a door.”

He’d lived. He was a skater kid in Vancouver, a city with an acute understanding of other cities, other cultures; but Vancouver didn’t really have a scene of its own so he knew he had to get out to be part of the world. First stop: college in Seattle, studying finance. Practical, because that’s what it took. Then Washington DC, more study, international business and finance, which included a year at Oxford. He’d travel down to London, go to the Blue Note, rave with Goldie and the Metalheadz crowd. Back in Washington, it was Homecoming at Howard University, with WuTang and OutKast. Then Luke had an interview on Wall Street which assured him once and for all that finance wasn’t his future.

He started skating again, met the Supreme team, started working with James Jebbia, who set him on the path to fashion which ended up with him through the wall from Lucie in Florence. Through all of his to-ing and fro-ing, she’d been in Zermatt, famous for skiing, climbing and hiking. Small wonder the guy who blitzed her with drum and bass made a major impression.

It was actually those early conversations in Florence which shaped their latest collection. The memory of Luke’s mid-90s moment when anything seemed possible, when the exchange of information between music, movies, media was endlessly exciting. “There was a feeling that new things were coming along that were very positive,” Luke remembers. “That feels really necessary right now because I almost don’t want to read the newspapers. It seems we’re really on a precipice somehow.”

And yet, he finds grounds for optimism, or at least some kind of faith in the future. “We have to be quite realistic about what we do,” he acknowledges. “It’s not a necessity by any stretch, but there is a qualitative level that keeps rising. Even just the idea of always pushing to make things that are better. Not disposable.”

And maybe it’s something as elemental as a new life that brings hope. Credit Ella Rose. Lucie claims that, at the very least, she’s brought an efficiency into their lives. “She’s a good get-out-of-jail-free card,” Luke agrees. “I guess, like most people, if you’re quite passionate about what you do, you find yourself going deeper and deeper into the rabbit hole. We’d stay in the studio until midnight, quite regularly. We actually don’t know Milan as we should because the work has just been so, so intense. But Ella Rose has put this quite strong finish line to every day, where we have to get home for a certain time to be able to put her to bed. And we really get things done by 6.45 that would once have taken us till midnight. And somehow that was superfluous, like did we really need to be doing that.”

But maybe the discipline of responsibility shaped their lives long before Ella Rose arrived. Then, it was just a commitment to each other, fierce enough to weather the ultimate long distance relationship, him at Supreme in New York, her in Paris. “I was basically at school in Paris and really taking it seriously. Luke was at Supreme. So I think we were just working really hard. And then we had us on the side. We probably didn’t know it was gonna be for that long. We took it as it was, not really having a big plan, like after three years, we can actually move together. It was just going along with the situation.”

They eventually married in 2007, and Luke moved closer. ‘We got to a point where it was either I would move to Paris or she would move to New York,” he says. “I was happy to come here.” Luke launched luxe streetwear brand OAMC, Lucie arc-ed through Vuitton and Balenciaga before landing at Christian Dior when Raf Simons was creative director.

On the surface at least, their worlds couldn’t have been more different, but Luke harks back to an article — American Vogue, March 1995 — which compared Chanel and Supreme and decided their approach was very similar. “A different product entirely, but the mentality of everything having to be a certain way is the kind of approach you take to anything if you care about making something well. The journey to get there is the same.” He parallels that with his and Lucie’s situation. “In a weird way, we really related to each other. Obviously, there’s the sort of creative exchange or just the general exchange of seeing shows or concerts or whatever, but there’s also this understanding, like, ‘Okay, I know what you’re going through.’ Even though it’s a very different environment, it’s still the same.”

And that’s how they came to Jil Sander together in 2017, the same year as the epochal strategic alliance between Louis Vuitton and Supreme. Fusion was in the air. Sander’s then-CEO Alessandra Bettari approached Luke. “I’ll only do it with Lucie,” he told her. It was always the plan that they’d work together one day. “But we didn’t think it was gonna happen this early,” Lucie says now. “I’m sure they probably had the idea that if I would do it, then she’s coming along because she had the chops in terms of high level European womenswear,” Luke adds. “I had no experience whatsoever in that world.”

So, looking back, why does he think he caught Bettari’s eye?

“Good question. I don’t know. Maybe my obsessive-compulsiveness.” He laughs. “Also, maybe not at all strangely, but Jil Sander and Helmut Lang were a massive, massive reference for Supreme at the beginning when I was working there. Helmut still had his store in Soho. It was very powerful. And I think, to this day, James still wears a lot of Jil Sander pieces. At Supreme, we really cared about making things good, long-lasting. I can’t speak for their approach today, but at that point, it was really literally go to Midtown and find some beautiful fabric from some Swiss mill.”

The symbiosis between street and salon has become something of a fashion trope, but with Luke and Lucie, the connection was umbilical to begin with, which was useful when they fronted up at Jil Sander, which had suffered several tumultuous years: Raf Simons leaving, Rodolfo Paglialunga arriving and leaving, Jil coming back… and leaving again.

“The connection we both had to the house was always there, in very different ways. Like I said, working in New York, it was an important reference point. And for Lucy personally, her mum was a big Jil Sander fan. And so, in a certain sense, it didn’t matter what it was like when we arrived. We were just like, let us give this a try and do our best to elevate it to what we imagined it to be.”

When the couple met Jil in Hamburg, she was very encouraging. It was at the time she was working on her retrospective in Frankfurt, but there were no archives to speak of. “She was very insistent on always looking forward, and if that’s your approach, maybe you don’t ever want to turn around and look back,” Luke recalls.

As for Luke and Lucie’s approach to Jil Sander, I assume it’s nothing as reductive as womenswear the way Luke sees Lucie, and menswear the way Lucie sees Luke. “I think you can’t escape that in a certain sense,” Luke accepts. “It’s quite lovely.” Lucie adds: “The way we work is we really do everything together — everything is kind of merging. Luke definitely has his eyes on the womenswear and I have my eyes on the men’s and, for sure, we add a different element. The clothes we do feel very personal to us, but I wouldn’t say exclusively. It’s not like every piece is, ‘What would Luke look like?’ There’s also a dream element. We have to make people dream, we have to make ourselves dream.” Still, she balks when Luke calls her the dreamer, even as she concedes she is intuition, while he is analysis.

“The process has become a bit more natural in a way,” says Luke. “I don’t think that we ever really struggled but now it’s very easy for us to get across what we want, even with each other. The dialogue is very easy at this point, you know. It’s exciting to maybe make things slightly unexpected.” There was a rather gorgeous summation of that notion at the end of the Spring/Summer show last September, with a clutch of outfits that married severe tailored tops with flurries of thick sequinned fringe. Poetry in motion. It was the Meiers’ refutation of minimalism in favour of purity.

“We don’t love the idea of decoration, but when we go there, we like it to have a very important boldness to it,” Luke explains. “So, in a way, it’s still as pure. Looking again at the Spring show, using those paillettes as a mass. It’s not delicate…”

“There’s a strength to it,” Lucie picks up the thread. ‘When we do the tailoring, there’s a strength in the masculinity of it. But there was also a strength in the sequinned dress in a way. There’s a power in that mass. And then to have the rigidity with the tailoring, always this masculine-feminine opposition. I think there’s an organic-ness. We like things that are a bit imperfect as well. We like to have that room for things to happen, where you feel the human touch, something a bit uncontrolled. But then beauty comes out of it.”

A photo by longtime Sander collaborator David Rhodes that accompanied the Spring/Summer collection showed a cascading closeup of those sequinned fringes. It was a perfect visualisation of the faint but alluring threads of narrative in their collections. More than enough to make me ask how a collection comes together for the Meiers. “We’re quite excited about shape and proportion at the moment,” says Luke. “We’re playing with colour and with specific graphic reference. I think next time we want to push shapes more. I would say, no matter what, there’s always gonna be the noise, you know, the white noise from something. Music is really always there, more than anything else. And also what’s happening technologically, with AI. What’s real anymore, right?”

Luke runs with the idea. “Like Elon Musk a few years ago, when somebody asked him, ‘Are we in the Matrix?’ And he said, ‘Well, if you look at the curve of the quality of CGI in video games over the last 20 years, and you extrapolate that over just 50 or 100 years. I mean, we’re already in the Matrix.’” Luke pauses. “But there’s something to be said for a beautiful wool that’s hand-stitched.”

That human touch is everything to the Meiers. Respect for the craft, respect for the individual who will eventually wear their creations. “There’s nothing more precious than when something is made for you,” says Luke. “I know we’re not doing haute couture, but that idea when you see a hand-stitch or a hand-embroider or anything that’s manipulated by the hand, I think there’s something quite soulful. And I say forward-facing all the time, which doesn’t mean we’re designing to be disposable or irrelevant, but to always be searching and feeling. What’s today and what feels like it should be presented now. It’s never nostalgic. Even though this season was a bit inspired by that, it was never designed to be a throwback.”

Speaking of which, there’s a particular silhouette in the Sander tailoring that reminds me a little of the classic Bar jacket by Dior, which also refers back to a challenging chapter in Lucie’s past, when she and Serge Ruffieux spent several seasons, couture included, heading the design team at Christian Dior while the brand sought a successor to Raf Simons. “You can’t get rid of the past,” she says now. “There are always things you come back to. But for me, it’s always the belly, very much feeling. Intuition. It’s not a big plan, it’s just coming.”

I’m calling it a love story. And baby makes three.