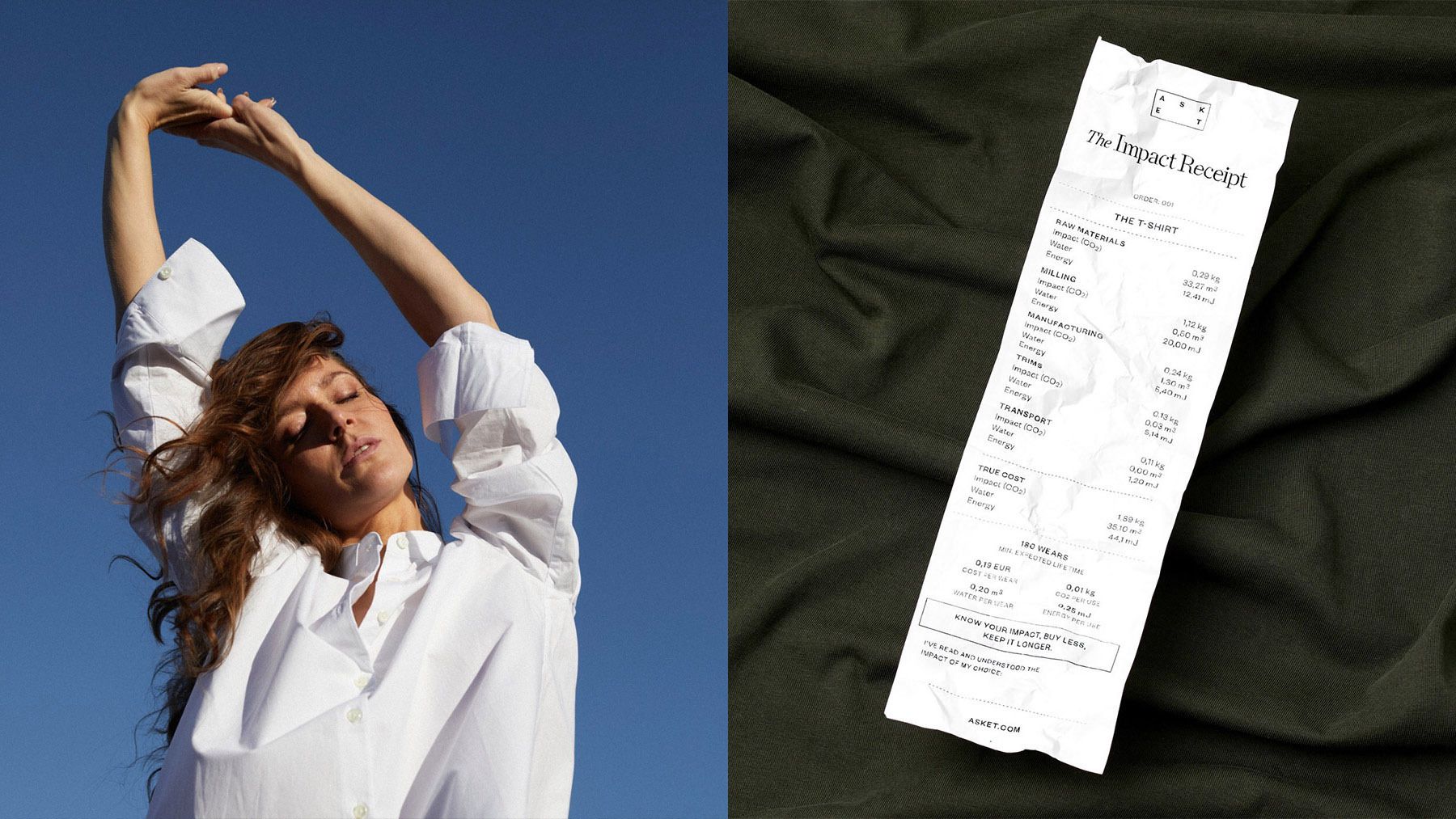

In 2020, Swedish essentials brand Asket set an aim to tag each of its products with an “impact receipt,” a tally of the greenhouse gas emissions, water and energy use associated with manufacturing and transporting each item in its collection of elevated basics.

Like most fashion brands, Asket doesn’t own the factories that make its clothes and the company had spent years painstakingly tracing the creation and delivery of each thread, button and zipper to help feed real data into its impact calculations. It had worked with the Research Institute of Sweden to pilot assessments for its core T-shirt, Oxford shirt, chinos and merino wool sweater.

But expanding the project across all of the company’s products proved even more complicated than it had thought.

Mapping the brand’s supply chain had been one thing, getting hold of and managing the data it needed for its impact assessments was another entirely.

Often information was out of date by the time the team could crunch through the numbers. And figuring out which datasets to use to calculate the footprint of raw materials, where the company had no primary data of its own, was a mind-boggling task that could radically change a product’s final impact score.

“It becomes immensely complex,” said Asket co-founder August Bard Bringéus. “It blew out of proportion.”

Last year, the brand partnered with carbon measurement platform Vaayu to help address this challenge. The tech start-up — whose other clients include secondhand marketplace Vinted, underwear brand Organic Basics and fintech businesses Stripe and Klarna — leans on AI to help companies run complex calculations on their carbon footprints. This year, Asket will finally roll out emissions receipts for all its products.

Vaayu is one of a flurry of digital platforms gaining ground as the industry confronts a looming onslaught of sustainability regulation. They promise neat, high-tech solutions to gnarly problems. But to really work effectively, the underlying data they rely on to inform impact assessments still needs to get much, much better.

‘A Completely New Dataset’

The fashion industry is just getting started experimenting with tech tools to help map, manage, interpret and present key information about brands’ sustainability efforts. But it needs to move fast.

There are roughly 40 different pieces of regulation set to come into play over the next four years, all pushing brands in the direction of greater transparency and greater understanding of their environmental impact, said Jocelyn Wilkinson, a partner at consulting firm BCG.

Companies are already struggling to meet the demands of new legislation in the US and Europe, from tougher requirements to prove products weren’t made with forced labour to mandatory disclosure of information on the environmental impact of products. Meeting all the new regulation coming down the pipeline, requires companies to keep track of roughly 70 different data points, many of which simply aren’t being gathered at the moment, said Wilkinson.

“We are speaking of a completely new dataset,” said Camille Le Gal, co-founder of Fairly Made, a Paris-based traceability and sustainability measurement platform used by companies including LVMH, Patou and SMCP. “What’s changed as well is that [before] the purpose of this data … was really a matter of satisfying the consumer, and now it’s a matter of satisfying the government.”

The service providers currently in play offer a variety of solutions to help companies efficiently comply with new regulations and make smart decisions to meet their climate ambitions.

The idea is that these tools can plug into a brands’ existing systems to scrape whatever data they have available, while also reaching out to suppliers to upload additional information. Smart algorithms are used to cross-check and verify data, comparing claims that suppliers’ cotton is organic against databases of certified mills, for instance. Finally, all that information is processed to generate an impact calculation in formats companies can use to inform more responsible design choices, communicate with customers and satisfy regulators.

In reality, few fashion brands are currently set up to enable that kind of functionality.

High-Tech, Low-Tech

Most fashion companies have a limited grasp over their supply chains, which means the information they have to feed into these new tech tools is patchy at best. What data does exist is often a mess, requiring painstaking work to clean up and start managing coherently. Typically, the further you get into supply chains, the less developed the data management systems and the more significant the environmental impact of the processes taking place.

“The data gap is pretty big,” said John Armstrong, chief technology officer at Worldly, the for-profit data platform spun out of industry group the Sustainable Apparel Coalition (SAC) and previously known as Higg Inc. “Getting the data is a low-tech, human-centric problem, [but] contextualising the data is a very high-tech problem.”

Bridging the gap is an arduous process and will take time. For instance, when Fairly Made onboards a new brand, the bulk of its initial time is spent reaching out to suppliers and explaining why they’re being asked for new data in different formats.

“The most difficult part is to gather the information,” said Le Gal. It takes on average four to five weeks to collect primary data from factories, but analysing that data is a matter of minutes, she said.

The flurry of data requests is a complicated, expensive and time consuming burden for suppliers, too, with particular nuances for different types of businesses. For instance, Sri Lanka-based Selyn Textiles works with home-based handloom weavers to produce its fabrics, adding a layer of complexity to any data collection exercise because the impact isn’t centralised around one factory.

“Collection of the data is a huge problem,” said co-founder and managing partner Selyna Peiris.

Emerging tech platforms say they can meet companies where they are and still help them model out useful information about their impact. For instance, Vaayu uses AI to mine existing databases and reverse engineer a product’s carbon footprint using whatever information is available. Say a brand knows a T-shirt was sewn in a factory in Cambodia using cotton made by a mill in China. Vaayu’s algorithm would look at the grid mix in both countries and the most relevant existing impact assessment for cotton to crunch out an emissions estimate.

Each calculation is accompanied by an accuracy score, so if the carbon footprint looks high or the accuracy score is low, brands know where to focus efforts to improve their impact and the information available, said Vaayu co-founder Namrata Sandhu.

Watershed, a similar platform that works with companies including Skims, Everlane and Shopify and was valued at $1 billion last year, says it can start to build companies a picture of their carbon footprint with just rudimentary financial data to begin with. They can then start to drill down to build a better picture.

“It’s important not to set perfect as the bar, because then we won’t move at all,” said Watershed co-founder Avi Itskovich. “It’s better to have a measurement that’s roughly right than perfectly wrong.”

Plugging the Data Gaps

Last year, Norway’s Consumer Authority took a hard view on exactly how “rough” companies could be when making sustainability claims.

The market watchdog sent shockwaves through the industry when it determined that data on the environmental impact of materials supplied by the SAC’s Higg Index – one of the industry’s most widely used data tools – was misleading when used to market products as more sustainable.

It blew open a debate about the quality of impact data available for materials like cotton and wool. Many existing datasets are old and based on broad averages, while the footprint of a particular material can vary wildly depending on where and how it is grown.

Country-specific grid data is a more reliable proxy because it’s less variable, but it still gives a skewed picture. Asket has worked hard to gain an unusual level of visibility over its supply chain, but opted not to use primary data in its first year working with Vaayu in order to set a baseline. It found that the resulting calculations are “vastly overstating” its impact because the assessment doesn’t see efficiencies its suppliers have put in place.

Tech platforms are working to address the gaps and build up their own access to valuable data.

On Tuesday, Worldly launched a new tool to allow manufacturers to upload impact data in real time, rather than responding to an annual survey. The information will be verified by certification company SGS. Last month, Watershed acquired emissions accounting and data firm VitalMetrics, which maintains a major emissions database.

The goal is for all this work to not only help brands meet regulatory requirements, but address their impact. Really understanding what it takes will require much more data gathering.

“Primary data is totally essential full stop,” said Wilkinson. That doesn’t mean reaching every field, farm and factory tomorrow. But long term, “any brand that kids itself with averages and estimations at large is not mature in their approach.”

For more BoF sustainability coverage, sign up now for our Weekly Sustainability Briefing by Sarah Kent.