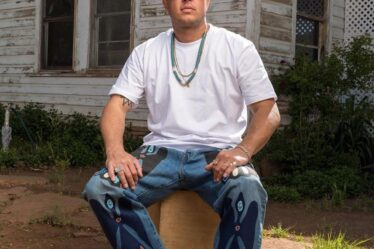

Buck Mason started as the brand with the “perfect tee.” Now if they fall short, they have no one to blame but themselves.

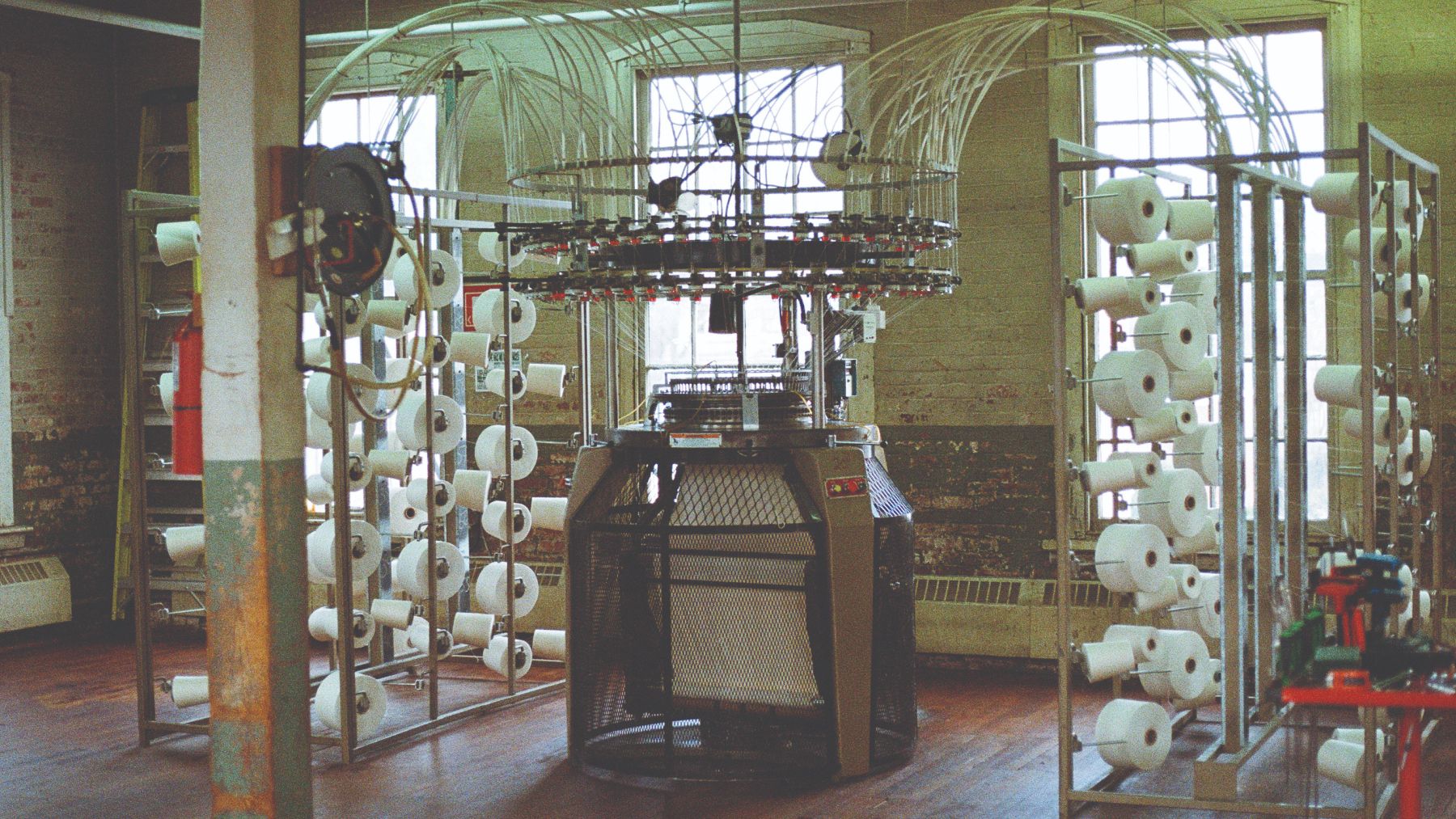

Last December, the brand, which started online in 2013 and now has over 20 stores in the US, acquired a closed knitting mill in Pennsylvania. Today, it makes its most popular T-shirts there.

The decision to get into manufacturing was largely about quality control, said co-founder and chief executive Erik Allen Ford. Buck Mason wanted to eliminate the possibility of expensive-to-fix issues on orders of its popular tees from outside factories. Moving production in house should make it possible to cut the time from design to production in half, and increase profit margins by as much as 10 percent in the next six to nine months.

“We’ve been in and out of factories domestically for ten years,” Ford said. “We just think we can make the best knitwear in the world by owning it vertically and owning the quality.”

When direct-to-consumer brands talk about “cutting out the middleman,” they usually mean taking distribution or advertising into their own hands. A small, but growing number are applying this philosophy to manufacturing as well. Men’s grooming brand Harry’s bought a blade factory in Germany in 2014; apparel seller American Giant bought a manufacturer in Middlesex, North Carolina the same year; and footwear maker Rothy’s created its own space in Dongguan, China in 2017.

In addition to quality control, having direct oversight of the supply chain can reduce shipping costs, get products to market faster and make it easier to head off problems. Operating a factory can be tedious for brands, but knowing where their products are in the manufacturing process provides its own peace of mind.

“In the beginning, it was just like we needed to be able to make the stuff that people were waiting to buy,” said Bayard Winthrop, founder and chief executive of apparel brand American Giant. “That surety of supply is a big deal.”

Who Should Open a Factory

Vertical integration — where a company owns multiple stages of production and distribution — is a common strategy among big brands. Luxury labels in particular have snapped up everything from flower growers to alligator farms and artisanal leather works to ensure access to rare inputs, and that their bags, shoes and fragrances meet exacting standards.

Operating a factory is especially ambitious for fashion start-ups, which are often founded by entrepreneurs with expertise in marketing or design, and would find keeping a factory humming more of a distraction than an inside advantage. And while Chanel has plenty of cash to buy a stake in a yarn manufacturer, smaller brands can often barely afford to pay their existing manufacturers, let alone spend millions of dollars on space and equipment to build one of their own. Finding skilled workers is also tricky, especially in the US, which has seen its apparel manufacturing sector shrink for decades.

Vertical integration works best when brands have established demand for their products, and don’t have a long list of vital investments competing for funding, such as opening stores or increasing advertising spend, said Benjamin Bond, a principal consumer growth strategy consultant at management consulting firm Kearney.

Buck Mason, for example, is profitable and used its own capital to buy its knitting mill. Harry’s started as a subscription service, which made it easier to predict demand for razors.

“If their demand is in any way variable and they are not seeing continuous solid growth, then they should not be making that investment,” Bond said.

Streamlining the Supply Chain

Brands often use in-house manufacturing for certain, critical elements of their supply chain, or as a place to innovate, rather than attempting to produce their entire product range.

Buck Mason doesn’t even plan to produce all of its tees, let alone categories such as jackets or trousers, at its Pennsylvania mill. The brand will continue to make accessories like its leather belts and wallets in Italy and parts of its denim line and special edition leather jackets in LA.

“You can’t vertically integrate and be world class in every category,” Ford said.

The brand’s sewers and designers can collaborate to make it easier to forecast how much cotton it needs to source or what it can do to make sure its tees last longer.

Securing supply is another motivation for investing directly in manufacturing.

American Giant — known for its range of made-in-the-USA basics — bought its factory in North Carolina in 2014. Earlier that year, the company was looking to increase its order volume of classic zip-up hoodies at one of the factories it worked with in San Francisco. Those plans were derailed when the factory said it had to reduce American Giant’s order capacity to accommodate Under Armour.

“It almost killed the business,” said American Giant’s Winthrop.

At the urging of an investor, and armed with venture capital, the company acquired a recently-bankrupt facility in North Carolina. Similar to Buck Mason, American Giant’s facility has become the designated hub for its knitwear items like the zip-up hoodie, sweatshirts and tees.

Supporting Innovation

When Rothy’s — which sells shoes and handbags made with machine-washable 3D-knitted materials — was launching its first slip-on sneaker in September 2018, it replaced a typically manual function. The knit-to-shape technology in the company’s knitting machines were able to fuse a yarn inside the upper of the shoes, allowing designers to lock stretch in certain areas and not in others. By doing so, the company reduced the number of people it needed to make the shoes and significantly cut down on waste, said Roth Martin, Rothy’s co-founder and president.

Such efforts have come as the company scaled its factory from one floor with nine machines to around 300,000 square feet and nearly 700 employees. Rothy’s continues to invest a portion of its annual profits in expanding its manufacturing capabilities.

“We’re always innovating on our products like a tech company might have version releases,” Martin said. “We want to learn how to really move the needle in doing what we do.”