A visitor to Shein.com will immediately be greeted with multiple pop-ups touting big discounts. Once they dodge those, they can browse row after row of product photos of varying quality – some featuring models shot in studio, but others awkwardly photoshopped or clearly computer-generated. Christmas deals are overlaid with falling snowflakes that look straight off of a Myspace page or Livejournal blog.

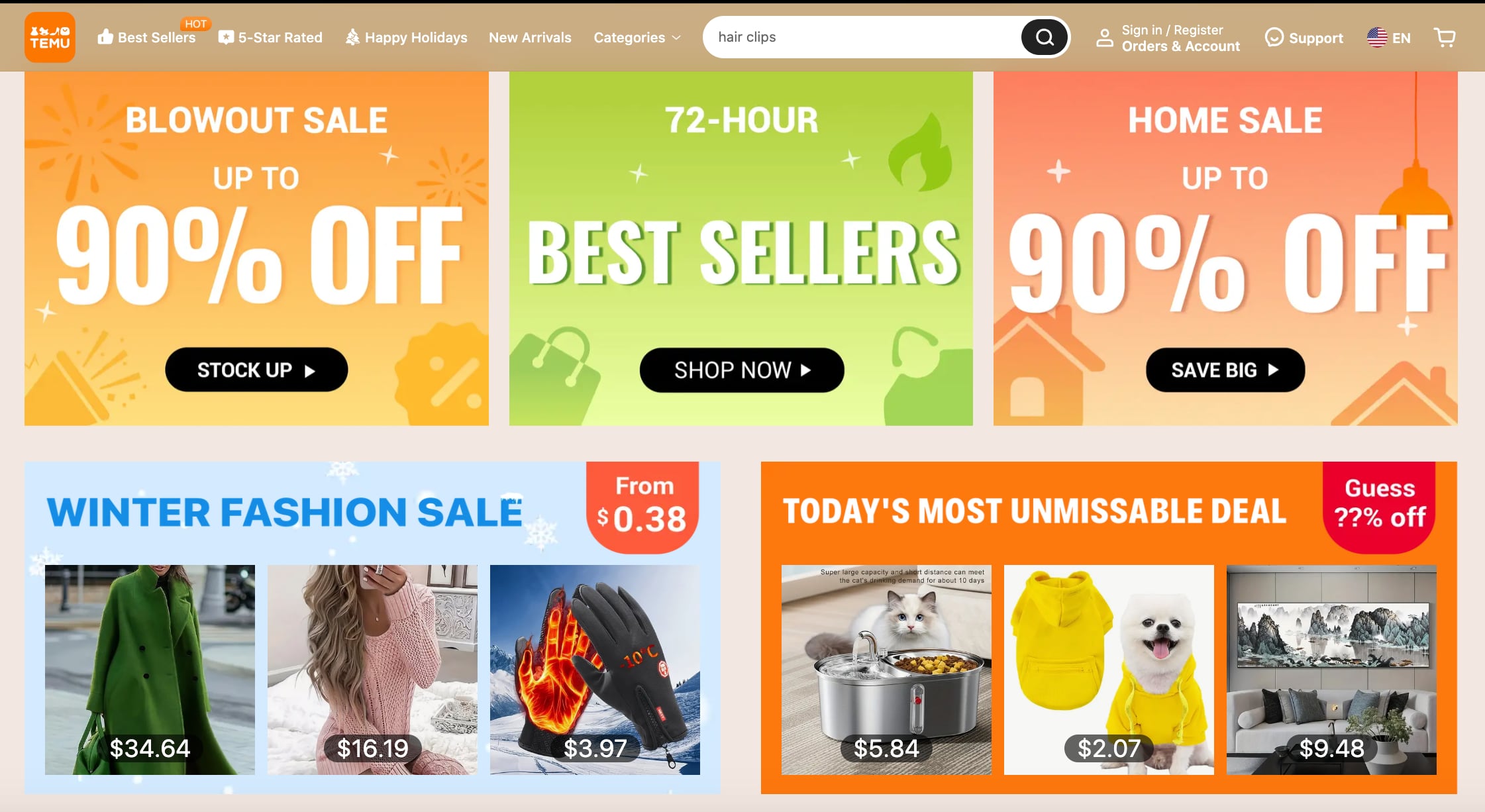

Over at rival Temu, it’s a similar jumble of messy text, haphazard photography and a dizzying number of products. Users encountering TikTok Shop after its September launch complained about heavy handed sales pitches for cheap-looking, unbranded products cluttering their feeds.

For Western consumers, the disconnect between this garish aesthetic and the multi-billion-dollar retailers behind them can be a head scratcher. Direct-to-consumer start-ups like Everlane and Glossier made a polished online store part of their brands. And though Amazon’s endless grid is hardly a paragon of great design, it’s relatively uncluttered, with products neatly displayed against a clean white background. There’s certainly no “spin to win” animated coupon wheel, as confronted visitors to Temu.com this week.

But there’s a method to the madness. Rather than conform to Western design standards, TikTok, Shein and Temu opted to stick with the busy visual formula that’s worked for e-commerce companies in China for decades, thanks to idiosyncrasies with how the country came online. While design connoisseurs may turn their nose up at these choices, the runaway success of these platforms may end up changing how their western rivals approach web and app design.

Chinese-Style UX

The clashing aesthetics comes down to some fundamental differences in how e-commerce works in China and the West. In China, most online shopping occurs on Tmall and JD.com, rather than individual brands’ websites. Amazon, Walmart, Target and other multibrand retailers do big business in the US and Europe, but brands are bigger players, particularly at the high end of the market.

Where Gucci or Zara use their websites to immerse visitors in their brands, with commerce an important but sometimes secondary priority, marketplaces are concerned first and foremost with selling as many products as possible. That mentality determines the look and feel of these websites.

The biggest Chinese e-commerce success stories in the West are all gravitating towards the marketplace model, rather than the brand model; hence the homepages crowded with products and coupons. Even Shein, which rose to prominence because of its vertical business model that enables it to create ultra fast small batch orders under its own name, is investing heavily in building out a third-party marketplace.

A second factor behind the business stems from the fact that most of China first encountered the internet through their phones, rather than desktop computers. To mobile natives browsing through wares on a smaller screen, the products displayed on Temu and Shein look less chaotic and overwhelming.

Chinese are also used to so-called super apps Alipay and Wechat, where they can do everything from pay bills to manage their bank accounts, call a taxi and of course, shop. To a super app user, there’s less cognitive dissonance in buying a luxury handbag in the same place you pay your water bill.

“The web design is usable. It works,” said Oren Schauble, founder of Valuable Studios, an agency that advises brands on digital marketing and e-commerce strategy. “They are getting things done fast and they are iterating fast, and if it isn’t broken, they’re going to run with it.”

Because these platforms compete on price, shoppers have lower expectations on UX. Schauble points out that western online stores targeting the mass consumer whether it’s Old Navy, Gap or Costco.com don’t look too dissimilar. Calling the negativity around the design of Chinese-owned ecommerce platforms “overblown”, he says the main gap in normalising it for a western lens is the quality of imagery.

It’s no coincidence that Gen Z shoppers in the West, who like their Chinese counterparts grew up with smartphones, are most accepting of the Chinese-style look of Temu and TikTok Shop. Young consumers also have less disposable income, and are more concerned with seeing how far they can stretch their spending rather than how pretty the online store looks, said Ashwinn Krishnaswamy, partner at Forge Design, a consumer branding consultancy.

“The younger generation is much more willing … to interact with what may be messy or challenging-to-use interfaces … if there is value in either the content or the outcome,” Krishnaswamy said. “For 50 percent off, I’m willing to deal with what may be a kind of messy interface.”

Gen Z isn’t just concerned about deals. They’re actively rejecting the design favoured by previous generations. Kitschy, brash and loud Y2K stylings are a purposeful choice among young-skewing brands at all price points. On TikTok, less-polished creators thrive. There’s even a purposeful lean into things that look “nonaesthetic” with that hashtag used over 125 million times.

Moving Upmarket

The busy design has helped TikTok, Shein and Temu win over the lower end of the fashion market. Whether they can sell pricier, branded clothes the same way remains to be seen.

Shein has begun taking steps to add (relatively) more premium goods to its product selection through partnerships with Forever 21 and Skechers, though it’s had few, if any takers among luxury brands. Temu and TikTok are likely to follow a similar path as the market for low-margin, unbranded goods becomes saturated.

Starting mass and moving upscale is harder than going in the other direction, said Doug Weiss, senior vice president of digital and e-commerce at WHP Global and formerly head of creator commerce and platform partnerships at Instagram.

Luxury brands may feel it’s too risky to associate their carefully curated brands with social media platforms and marketplaces that embrace the messy look. Instagram and Amazon have both struggled with this problem. And when many of the most sought-after brands are missing from a platform, it can be hard to attract high-spending shoppers.

“Regardless of whether Gen Z is willing to shop online, if the product isn’t there, they can’t,” Weiss said.

However, Alibaba and JD.com both managed to convince luxury brands to work with them in China over time, creating a special shopping portal experience for buying high end designer goods on their platforms. In 2015, Kering Group was battling Alibaba for hosting counterfeit products. Two years later it decided to drop the case and opened up several online stores on Tmall for its brands. Temu’s parent, PDD Group, got its start by appealing to thrifty customers in rural areas, and though it remains deal-oriented, it is now seen as a real rival of the big two with stores for big brands like Dyson and Adidas.

Temu, Shein and TikTok could follow a similar playbook in the US. However, Western shoppers already have websites and brands they like, and even Amazon’s efforts to carve out a luxury space for brands has struggled to gain momentum. Retraining them to embrace Chinese-style e-commerce – and not just in pursuit of a great deal – would “probably be an order of magnitude more expensive than in China,” Weiss said.

“You need to convince the US consumers to do something different to what they’ve already done,” he said. “But the opportunity still exists … people want a mobile optimised rich immersive shopping discovery experience.”