“Make America Ferrera Again.”

In 2016, when Rebecca Minkoff debuted a T-shirt emblazoned with that phrase — a play on America Ferrera’s name and Donald Trump’s slogan — it “didn’t feel like a risk,” the designer said. The actress and designer posed in the tees at Minkoff’s Manhattan boutique; Allure dubbed the collaboration “amazing” in an October 2016 headline.

Needles to say, Minkoff isn’t planning any Trump-themed novelty T-shirts this year.

“We’re seeing a big shift right now in sentiment in terms of what everyone thought was the right platform,” Minkoff said. “[The T-shirt] felt right at the time … And I’m not saying I feel wrong about it at all … but I’m of the mindset that people and things can change and shift as times change and shift.”

As the presidential primaries ramp up — or more likely, wind down after Trump’s thumping of his opponents in the Iowa caucuses last week — Minkoff isn’t the only one inside the fashion industry who plans to tread gingerly around politics this time around.

Politically outspoken designers like Minkoff and corporate behemoths like Nike have for years used progressive stances on hot-button issues to connect with consumers. But a conservative backlash and signs of audience fatigue around such messaging has raised the risk for engaging with topics like inclusivity, climate change and LGBTQ rights. A funny T-shirt is less likely to score points with young fashionistas, and more likely to trigger unfavourable coverage on Fox News and a boycott.

This year is shaping up to be particularly toxic, politically. Few brands see an upside in wading into the debate around the war in Gaza, where opinions don’t fall along predictable red-blue lines. And they’re especially wary of getting swept up in the US presidential election — a likely showdown between Trump and the equally unpopular incumbent, Joe Biden — where both camps will be looking to tear down symbols of the other side, whether it’s a campaign poster or a Nike swoosh.

“In the past, there were a lot of headlines that you could incorporate that were fresh and newer and safer,” said Stacey Widlitz, founder of SW Retail Advisors, a retail business consultancy. “This year, it feels, if you make a comment, it’s very polarising. And for larger brands, especially, you have to consider what is the upside if that goes wrong?”

But the industry can’t fully disengage, Widlitz said. Consumers have come to expect fashion and beauty brands to align with their worldview, and will notice if a label rebrands itself as apolitical. The goal now is having a voice without creating a political firestorm.

Or to put it more simply: “Don’t pick a side,” said Juan Manuel Gonzalez, founder and chief executive of G & Co., a retail and luxury consulting firm.

Playing it Safe

Marketing experts are predicting a return to the pre-2016 era, where brands mostly stuck to encouraging political engagement, without getting specific.

“It is more about ‘get out the vote,’ giving employees time off — things that safely say ‘’we’re encouraging people to take a stand,’” Widlitz said. “But you can still be clever about it.”

Certain brands are still well-positioned to engage on actual political issues. Companies that are already associated with causes, such as Reformation with climate change, Nike with racial justice or Athleta with abortion rights, will continue to be rewarded by their like-minded customers. Those same customers may also leap to a brand’s defence if it’s targeted by conservative activists.

Minkoff, for instance, has always emphasised women’s empowerment messaging at her brand. She’s in the past collaborated on products with politically outspoken women like Jessica Alba and Christy Turlington Burns to support nonprofits focused on women’s access to health care, education and social services.

“So 99 percent of my involvement and voice has been around encouraging women to vote because that’s my audience,” she said.

What Consumers Want to Hear

There are ways to thread the needle. Brands figured out long ago that racially diverse casting in marketing pleases liberal-minded consumers without alienating conservatives, while conservative preferences for marketing that celebrates traditional family structures without sexually suggestive content can have universal appeal too.

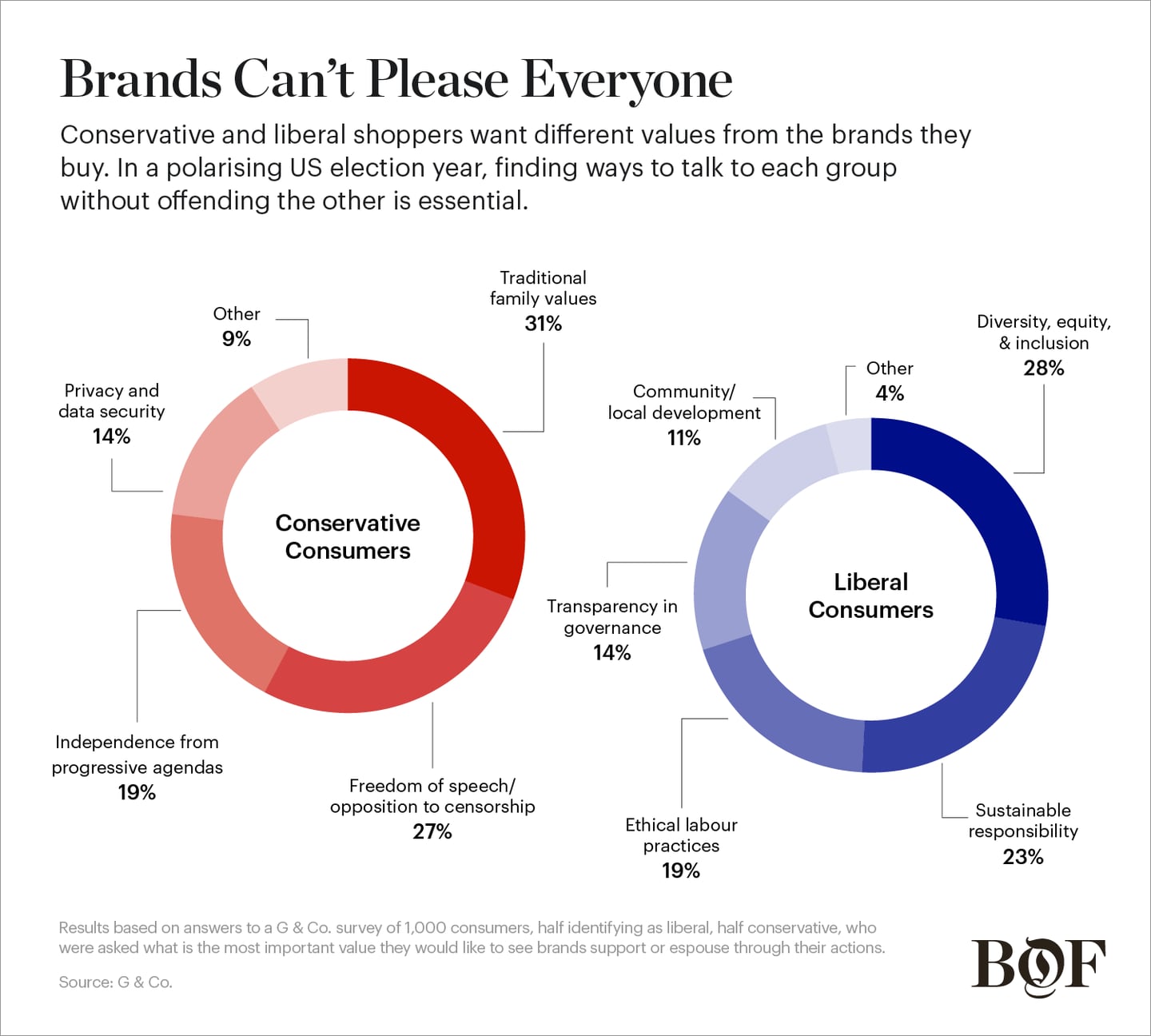

But there are a growing number of points of conflict, too. In a G & Co. survey of 1,000 US adults run for The Business of Fashion, respondents who identified as liberal said they were most interested in hearing from brands on topics like sustainability, diversity and ethical labour practices. But nearly half of conservative respondents said they want brands to steer clear of “progressive agendas” and support “freedom of speech,” phrases linked to across-the-board opposition to even the mention of the issues brands most often tap into when speaking to progressive customers.

If a brand does decide to join the fray, it needs to ensure it can be “brutally authentic,” on the topic and that its customers unequivocally “choose one political ideology over the other,” Gonzalez said.

One of the reasons this election year is more challenging for brands is that consumers have become savvier about topics like sustainability and diversity — safe, generic messages that play to both sides won’t cut it, experts say.

“If you choose sustainability or social responsibility, you have to be able to follow through on that,” Gonzalez said. “Don’t do it if your company is not following those guidelines and systems of being a sustainable or responsible brand. Consumers are smart enough to sniff that out now.”

A Backlash Plan

In this election cycle “every topic can be a minefield,” Widlitz said, and taking a stand means brands have to be willing to shoulder some backlash. Companies should create a plan for navigating pushback (in advance of any campaign or messaging) and it should be informed by very clear data that indicates that its core customers aren’t the ones who will be alienated by the stance, Gonzalez said.

Nike’s work with football player Colin Kaepernick, the American football player who kneeled during the pregame national anthem in support of the Black Lives Matter movement in 2018 remains the gold standard. The brand took what appeared to be a huge risk but with the knowledge that its message would resonate with the right group. Nike’s success, though, is far less common today — and it’s uncertain whether the brand would enjoy a bump that outweighs the backlash if it ran the same campaign in this climate.

“One of the big wins is, in the long-term, your brand is on the right side of history,” Gonzalez said.

For leaders like Minkoff, backlash is easier to endure (if not worthwhile) when they choose to engage on topics that are deeply personal.

“I wade in and out of politics based on two things: it has to be personal to me and it’s one of my brand pillars,” she said. “I can see where it goes wrong for companies that jump on a bandwagon or try to do virtue signalling.”

This year, Minkoff isn’t planning a product launch tied to the election (that could change, though) but she’ll continue her past endorsement of I Am a Voter, a nonpartisan organisation that encourages voting and civic engagement.

Most brands should not need to venture into political banter with their consumers, but their leaders should always be prepared to answer questions about “world events” (such as wars and humanitarian crises) in a way that “doesn’t brush the consumer off,” Widlitz said.

“When you do take a stand, there’s always going to be someone who comes out at you so you have to be willing to back it up” she said. “When the backlash comes, if it comes in a big wave, you have to hit that head on.”