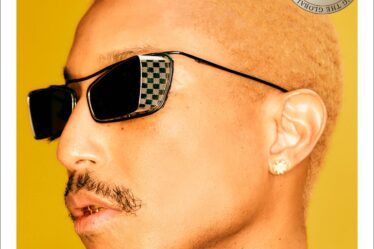

When Thebe Magugu won the LVMH Prize in 2019, he was nearly instantly flung into fashion fame. In the months that followed, he put on presentations at Paris and London Fashion Week, and dressed the likes of Rihanna, Naomi Watts and Lupita Nyong’o.

These days, Magugu wants to take a step back from the spotlight. Instead, the designer plans to focus on his native Johannesburg and Africa at large, where he believes could fuel the next stage of his growth. He was, after all, the first African designer to win the award doled out by luxury’s biggest company.

“I want to give back to my country and keep the brand local for as long as possible,” said Magugu. “I have had to make crucial decisions that may set us back financially, but advance the goals of the brand.”

Magugu specialises in contemporary womenswear, showcasing cultural and historical touchpoints of South Africa with bright colours and futuristic takes on traditional feminine silhouettes. His Spring/Summer 2023 collection, for instance, visually chronicled the devastating effect of fashion waste, largely from Europe and North America, on the African continent. His upcoming fall 2023 collection, which he will show via appointments at the Sphere showroom in Paris starting March 1, will explore African folklore, mythologies and oral history.

Without prominent African role models to look up to, Magugu believed that he, too, had to study in Europe in order to pursue his interest in fashion. After getting rejected from Central Saint Martins, Magugu enrolled at Stadio’s School of Fashion, formerly London International School of Fashion, in Johannesburg. Upon graduation in 2016, Magugu launched his namesake label. Being stationed at home would be the designer’s greatest strength as well as his greatest source of frustration.

“I had no social safety net and I often had to beg people to let me make them dresses just to afford rent,” he said. “I lived in downtown Johannesburg near Gandhi square, where I’d often hear gunshots in the middle of the night. To get out of there, I often had to choose buying fabric over buying dinner.”

Magugu’s first big break came from Woolworths, a South African clothing retailer, that tapped him to create a capsule collection for Spring/Summer 2017 which was showcased at South African Fashion Week. In 2019, he won the International Fashion Showcase Award held by the British Fashion Council, which called Magugu “a leader of his generation.”

His mission to bring the South African identity to a global stage earned him the LVMH prize that same year.

Suddenly, Magugu was swimming in partnerships with major wholesalers, including Bergdorf Goodman, Net-a-Porter and Dover Street Market. He became a coveted collaborator with brands like Dior, AZ Factory and Adidas.

Today, Magugu plans to continue catering to this global base, but will gently retreat from the public eye, favouring private viewings rather than high-production runway shows or presentations, he said, as well as events off the traditional fashion calendar. He will also prioritise his base of local clientele, who primarily shop on his website, which features his designs alongside his annual publication Faculty Press, a zine he created that is an amalgamation of South Africa’s untaught history and a cultural guidebook for creatives in the country.

“I am enjoying showcasing our universe through alternative means and media,” said Magugu.

For instance, alongside his first women’s runway show at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London last fall, the designer screened the documentary he made detailing his visit to Dunusa Market in Johannesburg, a site for secondhand clothes discarded by European and American consumers. The designer gathered materials from the market and reinterpreted them into the 25-look collection — and, ironically, by presenting it in London, the designer effectively sold the used garments back to Western retailers.

Made in Africa

Magugu’s commitment to being “Made in Africa” comes with challenges. His local artisan partners, for instance, struggle with meeting his demand for production. His factories in Johannesburg and Cape Town don’t have access to the latest innovations in apparel making and the quality isn’t always consistent. And as a result of South Africa’s routine power cuts, they also encounter regular delays.

“I would send fabrics to factories in Cape Town to be pleated and they would return damaged,” said Magugu.

Shipping is another obstacle. Because much of the infrastructure was set up during the colonial period rather than domestic efforts to build a logistical framework, it’s harder for Magugu to ship products within Africa than to North America or Europe, despite the closer distance.

As of last October, Magugu has signed on new factories in Italy and Madagascar to help with capacity and quality control. He’s not turning his back to his native partners, however. At home, he plans to host training initiatives for factory workers to bolster the quality of their work.

“I just have to be creative with the structures I set up that maintain the brand’s global presence,” Magugu said. “I think fashion often touts African designers, gives them opportunities to show but doesn’t consider the massive infrastructural rifts. And when things don’t work out, we blame the designer and not the industry.”

Additionally, his complicated supply chain has pushed the designer to rely less on wholesale with its strict deadlines for receiving products and more on the direct-to-consumer side of the business, where shoppers are largely local. His recent capsule collection inspired by eight of South Africa’s prominent tribes, for instance, sold out online in a matter of days.

Magugu plans to expand and relaunch his online store in April to serve a wider international audience as well and create more exclusive products. The designer aims to drive 60 percent of his brand’s revenue from the DTC channel in the next few years.

In wholesale, Magugu has plans to work with more stockists on the African continent. So far, the brand partners with only two stores in African countries outside of South Africa: ABY in Côte d’Ivoire and Alara in Nigeria.

For now, business is booming. The label has grown at an average pace 45 percent season-on-season, Magugu said.

“I want to … work from a paced, sustainable place where I am not under pressure to satisfy the grinding machine but serve my customers in a meaningful, direct way,” Magugu said. “Whether it takes me years to do so, at least it will be on my terms.”