Fashion’s days of operating with little to no government scrutiny are over. Now, the industry has to figure out how to comply with all the rules.

That’s not always simple. Brands and retailers operating in the US and Europe face regulations covering forced labour to greenwashing, with more likely to come.

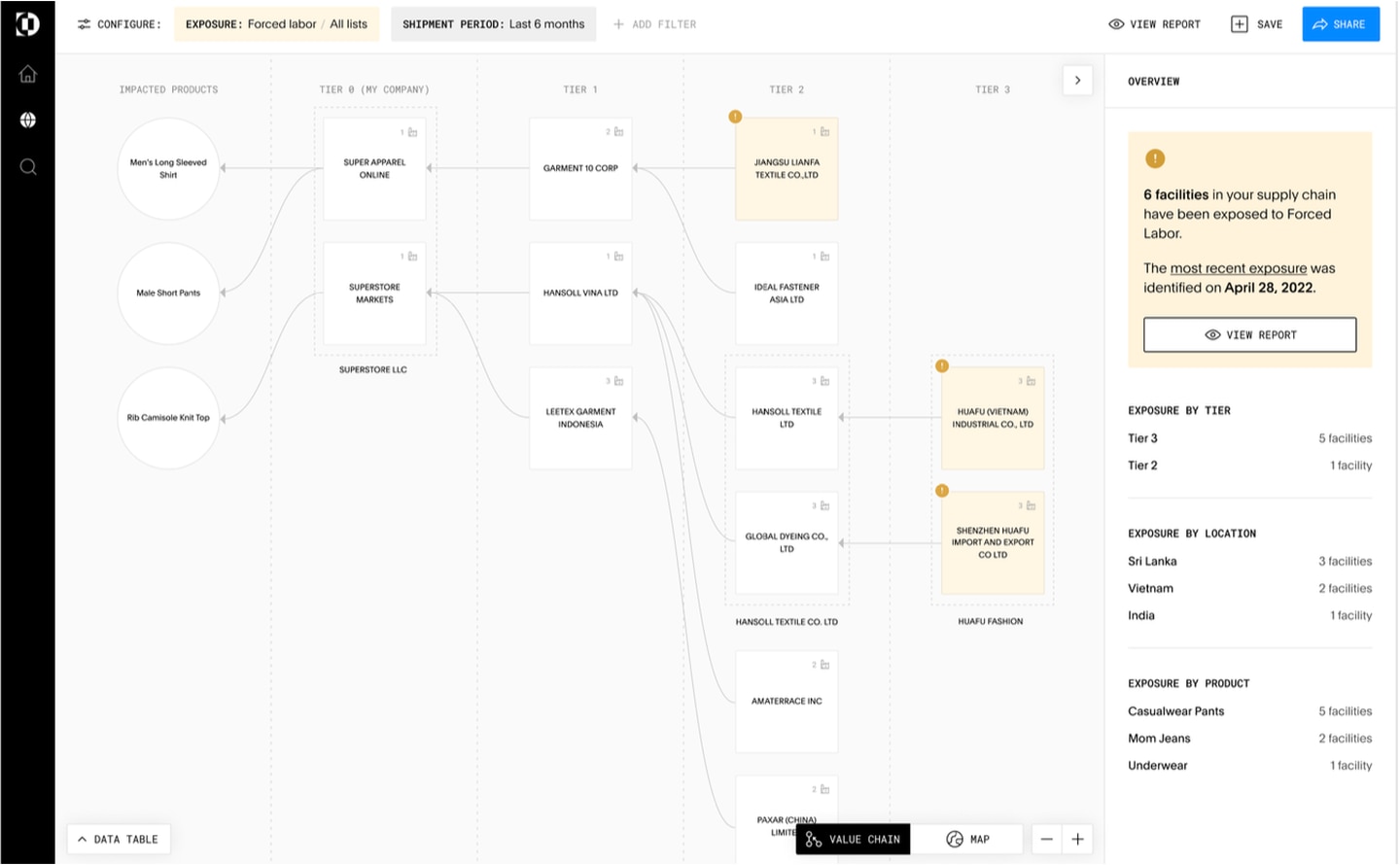

“It’s no longer acceptable from a regulatory standpoint, but even desirable from an economic standpoint, to simply manage your supply chain as a direct buyer-and-supplier relationship,” said Evan Smith, co-founder and chief executive of Altana, a tech-centric supply chain mapping company. “You need to be managing your upstream network as an actual system.”

The solution, Altana believes, is artificial intelligence. It compiles billions of data points on how goods move through global supply chains and applies AI to make sense of it all. The result, in Smith’s words, is “a shared source of truth that is used by manufacturers, retailers, brands, logistics providers and government agencies as a common operating picture.” Like Google Maps for supply chains, he said.

Altana said it already has a number of customers in fashion and textiles, though it couldn’t disclose any names. But its platform received a public vote of confidence last week when US Customs and Border Protection struck a multi-year deal with the company as it works to block goods it believes to be made by Uighur forced labour in China’s Xinjiang.

The issue has been of particular interest to fashion since Xinjiang is the epicentre of cotton production in China, the world’s biggest producer of textiles and clothing. CBP has proved it’s willing to block goods under the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act. Official statistics show it has denied 812 shipments of apparel, footwear and textiles totaling nearly $34 million in value from entering the US since June 2022.

For brands and retailers, it can already be a struggle to determine the origins and impacts of the materials they use for their products. Many are turning to technologies such as blockchain and AI as an answer.

“The bulk of our prospects who are trying to solve the forced-labour problem are from the apparel and textile industry,” said Amy Morgan, Altana’s head of trade compliance. “If it’s cotton, it’s tracing back to a farm, which is almost in some cases easier than synthetics that trace back to oil.”

While CBP agents will use Altana, the purpose of the platform isn’t to flag shipments. It’s to provide customers with a clear, up-to-date picture of the full value chain for different goods as well as insights for businesses, like how to structure your supply chain to take advantage of free-trade agreements, minimise tariffs and manage risk. A research brief Altana created on tracking ties to Xinjiang includes an example of a real apparel seller whose name has been changed. It gets into granular information about its supply chain down to details like shipments of specific fibre blends from yarn suppliers.

But it’s hard enough for fashion businesses to gather this information on their own products, so how does Altana do it?

Smith said they collect a mix of public and non-public information. The public information includes any data they can scrape from the internet as well as commercial data sets they purchase. (They’ve spent millions on those, Smith noted.) But that’s not enough to create the full picture they need, so they also gather non-public data siloed in customs authorities, logistics providers, financial firms and more through what they call “federated learning.”

“Nobody wants to share their data with each other and nobody wants you to pool all their data, but virtually all of the big data and AI computing platforms typically require you to centralise all the data in one place,” Smith said. “Let’s just embrace that fact and bring the platform down to the data and not the other way around.”

Altana’s customers can’t see raw data from other companies, but they have access to the insights Altana gains from it — for instance, knowing how a yarn provider connects to a specific textile mill that supplies numerous big brands.

To create a useful picture from the information takes more than just gathering records, however, which is where AI comes in.

The sheer volume of data is overwhelming. For a fashion company to sift through and manually decipher which raw materials went into a yarn that was woven into a fabric they used for a product would be impossible, according to Smith. Altana uses AI to extract the information it needs from billions of records in different languages and formats, and then to analyse them, establishing connections between companies, determining what’s relevant and deriving useful insights for businesses.

Other companies, such as Sayari, are also trying to make it easier for businesses to spot risky commercial connections, or using AI to help brands optimise their supply chains, as in the case of Hyran Technologies. The hope is that technology can help companies navigate one of the most complex parts of running a globalised business.

Smith ultimately envisions Altana helping companies make international trade easier in other ways, too, such as retailers being able to fast-track clearance of their imports through customs if they share their data with CBP on the platform, similar to the options that let pre-checked travellers speed through security in airports. While they’ve started by appealing to big players such as government agencies and large logistics providers, their goal is to start bringing smaller ones onto the platform too, including fashion companies. (Smith previously ran a business that focused on automating the apparel and textile supply chain, while Morgan started her career on trade issues at Nordstrom.)

“Our vision is for everybody who’s trying to do the right thing in the global supply chain to be connected into this platform,” Smith said.