It’s fair to say the launch of the Book 1, Nike’s latest basketball shoe and NBA star Devin Booker’s first signature sneaker, was a botched job. Fans ridiculed that the first release of 500 sneakers took place in Miami, on the other side of the country from where the Phoenix Suns guard played. Then came criticism of the shoe itself: Many called its colourways limited and unoriginal, saying it looked like a casual sneaker rather than one designed for a professional athlete.

Booker himself appeared to agree. Under a Complex Sneakers social media post on Jan. 20 that asked, “Is Nike fumbling the D Book 1 launch?”, he commented: “A lot of people feel the same way,” with a crying-face emoji. NBA legend and president of Reebok basketball Shaquille O’Neal seized the opportunity to attempt to recruit Booker to his brand via a cheeky Instagram post.

The Book 1 launch strikes at the crux of Nike’s predicament. The brand remains the undisputed leader of the sportswear category, boasting annual revenue of $51 billion, including $6 billion from Air Jordan, after nearly 40 years the most successful athlete endorsement deal in history. Nike maintains a hefty roster of the world’s elite athletes and sports teams, who break records, win medals and lift trophies wearing the “swoosh” logo.

But after decades of rapid, almost uninterrupted growth, there’s an emerging consensus among analysts, industry insiders, loyal customers, athletes and employees past and present that Nike is fast becoming just another sneaker brand.

In December, Nike slashed the outlook for its fiscal year ending in May, predicting sales would grow 1 percent. That would mark the company’s worst performance since the late 1990s, other than the pandemic year of 2020 and the 2009 recession.

Sales have disappointed quarter after quarter in the US and China, Nike’s two most important markets. The brand has re-entered wholesale partnerships it walked away from a few years ago, a tacit acknowledgement that efforts to drive more sales through its own channels haven’t paid off as hoped. Investors aren’t betting on a rebound anytime soon. Nike shares are down 20 percent in the last year, while the stocks of rivals, including Adidas, Lululemon and Hoka-owner Deckers, have soared.

It’s hard to pin Nike’s problems on any one cause. But sneaker industry insiders trace many of the brand’s shortcomings to decisions made early in the tenure of John Donahoe, who was named chief executive in January 2020. His arrival came amid an exodus of veteran designers, marketing gurus and executives. Several waves of restructuring caused further upheaval. Decisions once left to the heads of categories such as basketball or running were centralised. The company invested ever-more design and marketing resources into its booming retro sneaker business, capitalising on seemingly bottomless demand for iterations on vintage Jordans and Air Force 1s.

These strategies initially boosted the business. Nike’s sales shot up 19 percent in its fiscal year ending in May 2021, and two years into Donahoe’s tenure, gross margins climbed to a six-year high of 46 percent. But even as Jordans were dominating the StockX sales charts and Dunks were flying off the shelves in their millions, it was rapidly losing ground in another category where the Nike name was once dominant: performance products.

Shoes, apparel and other gear for elite athletes and amateurs alike were not all that long ago the core of the Nike brand. Performance prowess and association with superhuman athletes were hammered home by culture-shaking ad campaigns like the iconic Air Jordan commercials by Spike Lee in the 1990s and the “Just Do It” slogan. In recent years, however, you’re just as likely to run into campaigns on Nike’s Instagram promoting easy slip-on shoes for children alongside content featuring Olympians and all-stars. The brand has also pared back its culturally savvy, on-the-ground teams in key cities around the world, instead trying to dictate culture out of Beaverton.

In a move symbolic of Nike’s new direction, Tiger Woods, the athlete most closely identified with the brand after Michael Jordan, left in December after 27 years. He’s expected to announce his own sportswear line next week.

“The Donahoe era feels like to me it’s on shaky ground, marred by layoffs, a lack of ingenuity in terms of product and innovation — something that people at the brand itself complain about,” said Mike Sykes, sneaker expert and founder of The Kicks You Wear newsletter. “Product has felt repetitious. There’s a sameness about it, where other brands have brought new things to the table.”

Executives in Beaverton have acknowledged they’ve hit a rough patch. Publicly, they blame an uncertain economy and newly cautious consumers for slow sales, while promising to step up innovation in fast-growing categories such as running. The company in December announced it will cut costs by $2 billion, with more layoffs expected.

“Areas of potential savings include simplifying our product portfolio, increasing automation and the use of technology and streamlining our organisation,” Donahoe told investors at the time.

Nike is still the biggest sportswear brand by a wide margin, and its swoosh logo still adorns the clothing and footwear of everyone from elite athletes to city commuters and streetwear cool kids. Recapturing the magic is high on the agenda for Donahoe, who has placed the need for innovation and fresh products at the heart of his turnaround plan for the brand.

“Some of the greatest legacy brands in the world are facing an identity crisis as we undergo massive social, economic and cultural change,” said John C Jay, former global executive creative director for Wieden+Kennedy, the Portland-based agency behind “Just Do It”. “Whatever challenges that Nike may face today, I have complete faith in its ability to meet the zeitgeist.”

A Troubled Reign

For almost all of its first six decades, Nike was run by lifers: The CEO role was held by founder Phil Knight until 2004, and by Mark Parker, who joined the brand as a footwear designer in 1979, from 2006 until 2020. (In between there was William Perez, the only outsider before Donahoe to have the top job. He lasted less than two years.)

Donahoe wasn’t entirely new to Nike, having served on the company’s board since 2014. But the former eBay CEO came from a consulting background, where Parker and Knight were laser-focused on product and brand marketing.

An exodus of key staff closely associated with the brand’s golden era soon followed Donoahoe’s arrival. Among the leavers were Sergio Lozano, a Nike employee since 1990, credited for the creation of the Air Max 95 sneaker, Nate Jobe, who oversaw Nike’s “The Ten” collaboration with Virgil Abloh’s Off-White, and Tom Rushbrook, global senior design director.

Donahoe set about driving a transformation of Nike’s business that relied on data-driven insights rather than cultural and creative nous. At the time, this was cheered by investors keen on making the brand more efficient, protecting margins and creating a seamless experience for consumers moving between the brand’s websites, social media, SNKRS app and retail stores.

Internal corporate restructurings rarely get much attention from the outside world, but it’s reflective of Nike’s role in the culture that these moves were dissected far and wide. Crucially, they displeased influential types who Nike has always relied on to build the brand mythos.

“Donahoe era: Alienated retail partners from mom and pops to Foot Locker Inc. Fired employees with decades-long experience that understood Nike secret sauce. Took the fun out of a lot of their advertisements. Became too reliant on retro. Ended sport categories,” Nate Jones, an NBA agent at leading athlete management firm Goodwin Sports, wrote on X in January.

The changes were felt most in parts of the Nike business most closely associated with the “Just Do It” ethos. Nike Basketball — a relatively small contributor of sales that plays an outsized role in the brand’s marketing and in establishing its performance credentials — in particular has taken several hits in recent years, with Booker’s shoe launch the latest.

In December 2022, the brand terminated its deal with Kyrie Irving — one of Nike Basketball’s highest-profile athletes at the time, whose top-selling sneaker was worn on-court by 50 NBA players — after the star shared a link to a film containing anti-semitic views. The partnership was fraught well before them: Irving in July 2021 described the upcoming Kyrie 8 sneaker as “trash” and claimed to have had no input over its design or related marketing.

Nike Basketball still has a deep roster of NBA superstars, including LeBron James, the only athlete other than Michael Jordan to have a lifetime deal with the brand. But the brand’s struggles on and off the court have opened the door for Adidas. Largely an afterthought in the basketball category since the rise of Air Jordans in the 1980s, its Anthony Edwards signature sneaker is now considered by sneaker experts to be one of the best performance basketball shoes on the market.

“Basketball used to be one of the brand’s strongest points and now I’m not sure where it’s even at,” Sykes said. “There’s a lot of sameness coming out of the brand. Every single signature shoe they have looks like a different iteration of the Kobe sneaker.”

Turning to Veterans

Nike doesn’t deny something has to change.

“We’re prioritising getting back on our front foot and identifying our key areas of growth: innovative product, distinctive storytelling and offering differentiated marketplace experiences,” said Nike chief communications officer KeJuan Wilkins.

The restructuring announced in December is the latest in a series of moves to shake up the culture in Beaverton. The brand has promoted executives associated with the good old days into key roles overseeing innovation, design and marketing. Among them was John Hoke, a 31-year Nike veteran, who now heads innovation under Heidi O’Neill, president of consumer, product and brand and who has been with the company since 1998. Craig Williams, a relative newcomer but who has been fundamental to Jordan brand’s roaring growth in recent years, was promoted in May to oversee matters such as supply chain and distribution on the Nike side of the business.

Reviving innovation at Nike will take more than a few executive appointments.

One of the brand’s last transformative breakthroughs was “Flyknit,” first introduced in 2012, a fabric that allowed Nike to create a super-lightweight upper — the entire part of the shoe covering the foot — with less material waste in production. Flyknit became an essential component in everything from running shoes to football boots to lifestyle sneakers.

But since then, Adidas launched its Boost technology, On released CloudTec and Hoka’s arched Meta-Rocker sneaker design has changed the face of performance running and premium lifestyle footwear. Nike’s Pegasus and other running shoes remain top sellers, but the momentum is clearly with its rivals.

“It’s such a competitive market right now — far more so than years gone by,” said senior research analyst Jessica Ramirez of Jane Hali & Associates.

Consumers and investors will be able to judge for themselves when products from the next phase of Nike’s turnaround hit the market later this year. The Air Max Dn lifestyle sneaker, for example, set to launch in March, is billed by Nike as a futuristic silhouette that carries its most advanced “Air” technology yet. Rumours are already swirling in sneaker forums about a potential Air Max Dn tie-up with streetwear giant Supreme.

“The second half of fiscal 2024 represents the start of a multi-year product innovation cycle that will introduce new franchises, concepts and platforms,” Donahoe said in December.

Nike’s Identity Crisis

Shiny new footwear technology will only go so far in solving Nike’s woes. The company needs to recapture its original secret sauce: the allure of its brand, amplified by marketing moments that double as cultural touchstones.

“I’ve missed more than 9,000 shots in my career; I’ve lost almost 300 games; 26 times I’ve been trusted to take the game-winning shot and missed; I failed over and over and over again in my life… and that is why I succeed,” said Michael Jordan in “Failure,” Nike’s 1997 ad campaign, considered to be one of its greatest of all time.

For decades Nike was known for its reactive, inspirational and sometimes controversial campaigns, which flexed its unapologetic “Just Do It” mentality along with its association with serial winners like Michael Jordan, Serena Williams and Kobe Bryant, linking their status as superhuman athletes with the Nike swoosh and the products it adorned. The Air Ship sneaker (a precursor to the Air Jordan 1), after all, was famously worn by Jordan in his rookie season despite breaking NBA rules. Nike paid fines from the league every time Jordan stepped on the court, knowing the value of the publicity and notoriety the shoe would receive.

A more recent example is the Weiden+Kennedy-produced “More Than a Londoner Campaign” in 2018, which celebrated the brand’s role as a status symbol among London’s gritty urban culture, booming grime music scene and its African diaspora, years before it was seen as “cool” or commercially advantageous for brands to do so. The campaign is still revered as a case study by marketing experts and appears in countless #sportsmarketing LinkedIn ramblings to this day, dissecting how Nike once again was able to lead cultural discussion through authentic and fearless marketing.

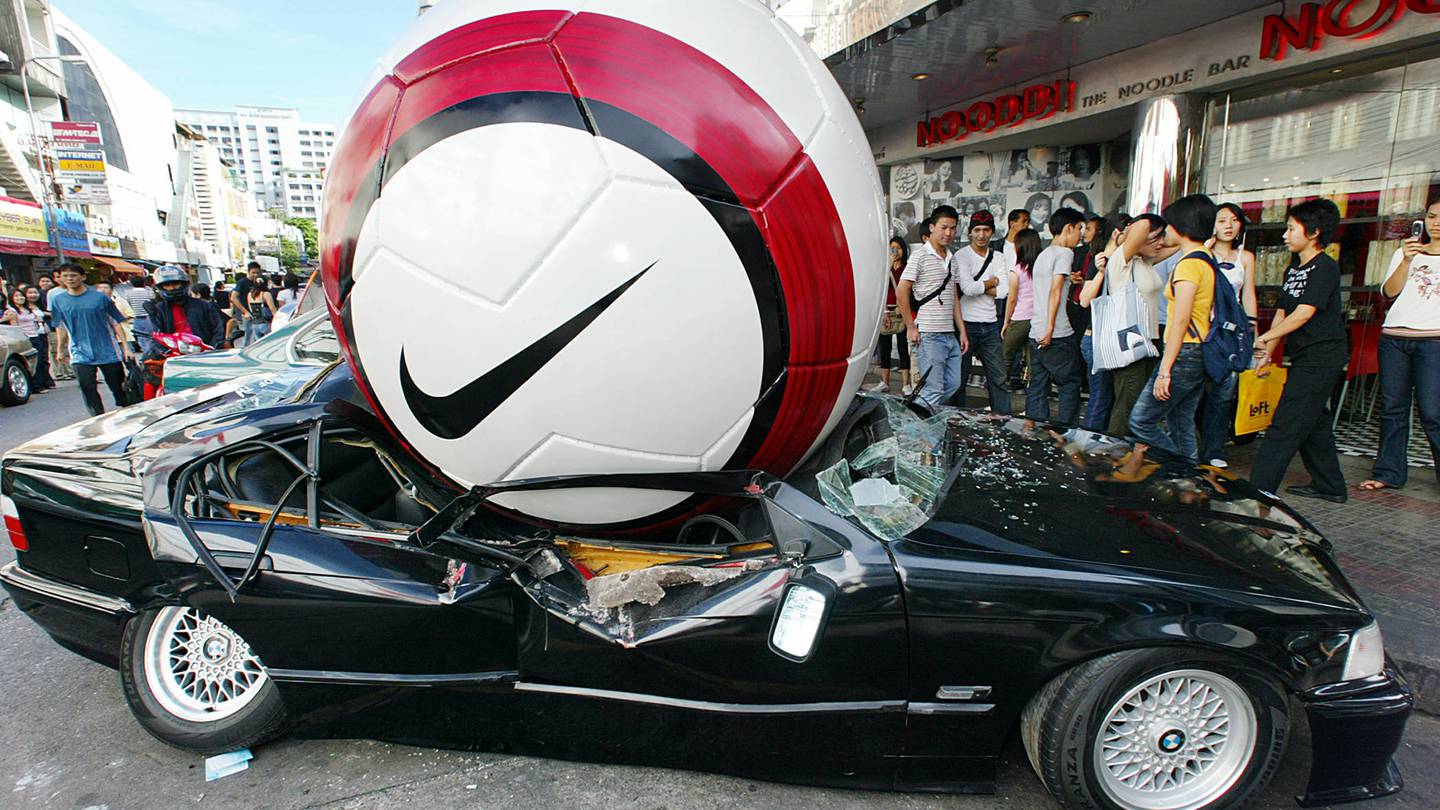

There are also weird and wonderful examples of Nike’s out-of-home advertising tactics. For example, the brand stunned shoppers and passers-by outside a busy Bangkok shopping mall by crushing a BMW sports car with a supersized Nike swoosh-branded football to publicise the brand’s role at the upcoming Euro 2004 football tournament.

Today, Nike ads often embrace the mundane, promoting neighbourhood running clubs. Recently, influencers shared photos and videos from Nike-sponsored line-dancing sessions on Instagram. This isn’t to say the brand no longer flexes its association with the likes of LeBron James, Serena Williams or Cristiano Ronaldo. But Nike’s tone has changed since its heyday, becoming more mass-market focused — perhaps a reaction to its competitors’ success in courting regular consumers with inclusive, aspirational marketing that didn’t focus on being the fastest, fittest or strongest.

It’s also partly an acknowledgement from Nike that since the rise of social media, ad campaigns tend to have lesser impact or reach. As a result, Nike marketing now comes across as safe, working with local influencers or pop-culture figures to target micro-communities of consumers — in the absence of its city-specific culture marketing teams — a far cry from the brand’s association in years gone by with the crème de la crème of athletic greatness.

“I don’t think Nike leads culturally as much as it used to,” said Christopher Morency, former editorial director of Highsnobiety and founder of brand consultancy Edition+Partners.

But the old formula still works, only now it’s often in the service of Nike’s competitors. When Adidas launched Anthony Edwards’ sell-out AE 1 performance sneaker in December, a month later it came out with a campaign straight out of the old Nike playbook. In the video, the NBA youngster is with a friend looking over a duffel bag, pulling out competitors’ signature basketball shoes, including Ja Morant’s Ja 1 (Nike), LeBron James’ Air Zoom Generation (Nike) and Puma athlete LaMelo Ball’s MB.01 sneaker. He discards shoe after shoe with remarks like “These ain’t nothing, hell no,” until he pulls out the final shoe, his AE 1.

“Oh yeah, these the ones. The colour, the feel, the look. These the ones for sure. You know how I know? Cause they mine, crazy man,” he says, as the video ends.

The confidence of an up-and-coming NBA star, Adidas’ underdog status in the basketball world and a compelling product instantly won over consumers, sending the campaign viral and drawing comparisons to the brashness of Nike’s early Air Jordan campaigns.

The Adidas commercial laid bare how, more so now than ever before, Nike needs its swagger back.

“It’s what so many brands seem afraid of doing these days. They go out of their way to not mention the competition as if it just doesn’t exist,” Sykes wrote in his newsletter, reacting to the commercial. “No, fam. It’s there. Acknowledge it. Tell us why your thing is better than their thing. That’s the name of the game here.”